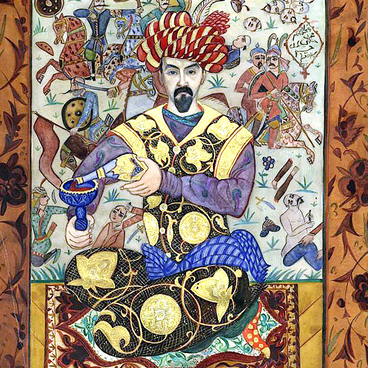

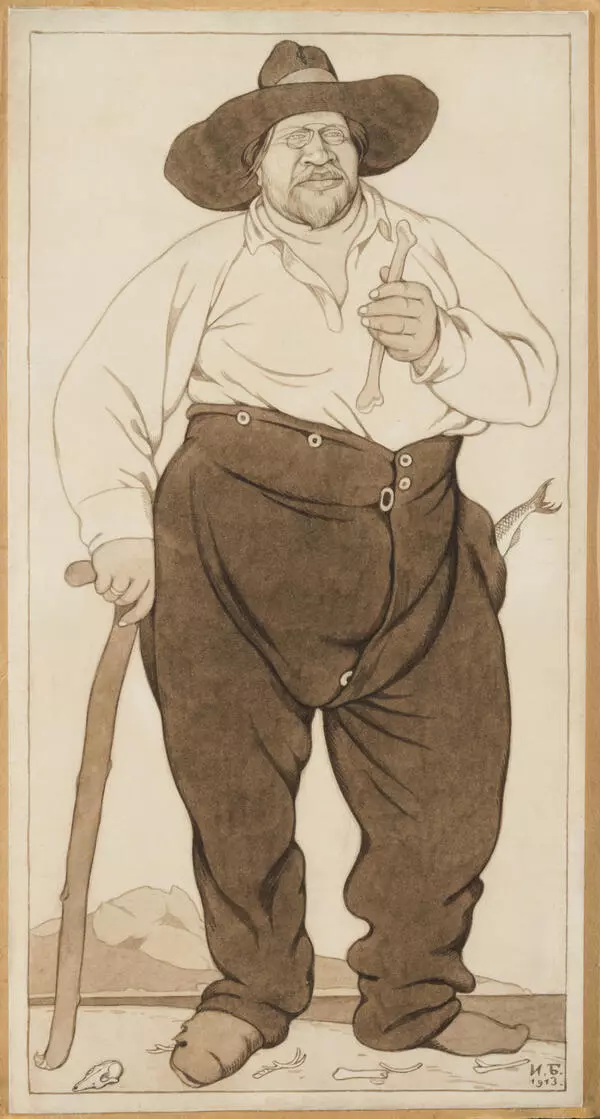

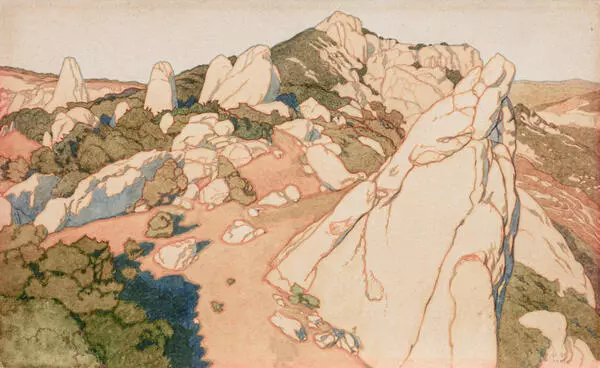

The presented portrait of an Egyptian boy was painted by Bilibin according to the aesthetic principles of the “World of Art” graphic portrait that developed in the second half of the 1900s — early 1910s. Members of the artistic movement “World of Art” were distinguished by the desire to convey not so much the individual characteristics of a model and their psychological state at the moment, but the common features inherent in the portrayed as a representative of a specific category of people.

There are almost no portrait sketches and studies in the artist’s albums. We will not find a quick and dynamic brush stroke that captures the most specific features of the model, their unique gestures and facial expressions in Bilibin’s works. He approached each of the portraits thoroughly, without haste, looking at the model for a long time, knowing that the sheet of paper that his hand touched at least once should turn into a finished easel work.

The Arab portrait series is distinguished by detailed depictions and even a certain naturalness of the artist’s style. Bilibin sought to capture the ethnic type as accurately as possible. The artist, fascinated by originality, searched for his characters in the Muslim quarters of Cairo and met them on his trips to Egypt and Arabia. It is no coincidence that the names of the heroes are not mentioned in the titles and only their age, national or social affiliation is indicated. Portraits are monotonous, static, Bilibin himself called them “heads”.

In the Arabic series, the artist fathomed the secrets of the most ascetic materials — pencil and paper, the surface of which is perceived as a space flooded with a dazzling sunlight. In the “Portrait of an Egyptian Boy”, Bilibin demonstrates a brilliant mastery of stain painting and shading. Reflections fall on the shaded parts of the cheeks, temples, and neck, while complex halftones are transmitted by the finest gradations of light gray on dark gray. The portrait is also skillfully constructed in terms of anatomy: the shoulders and part of the clothes on the chest are slightly outlined. The figure seems to protrude from a neutral background.

The portraits from the Arabic series expand and enrich our understanding not only of Bilibin’s oeuvre, but also of the portrait characteristic of the “World of Art” movement in general, for which images of peasants were very rare.