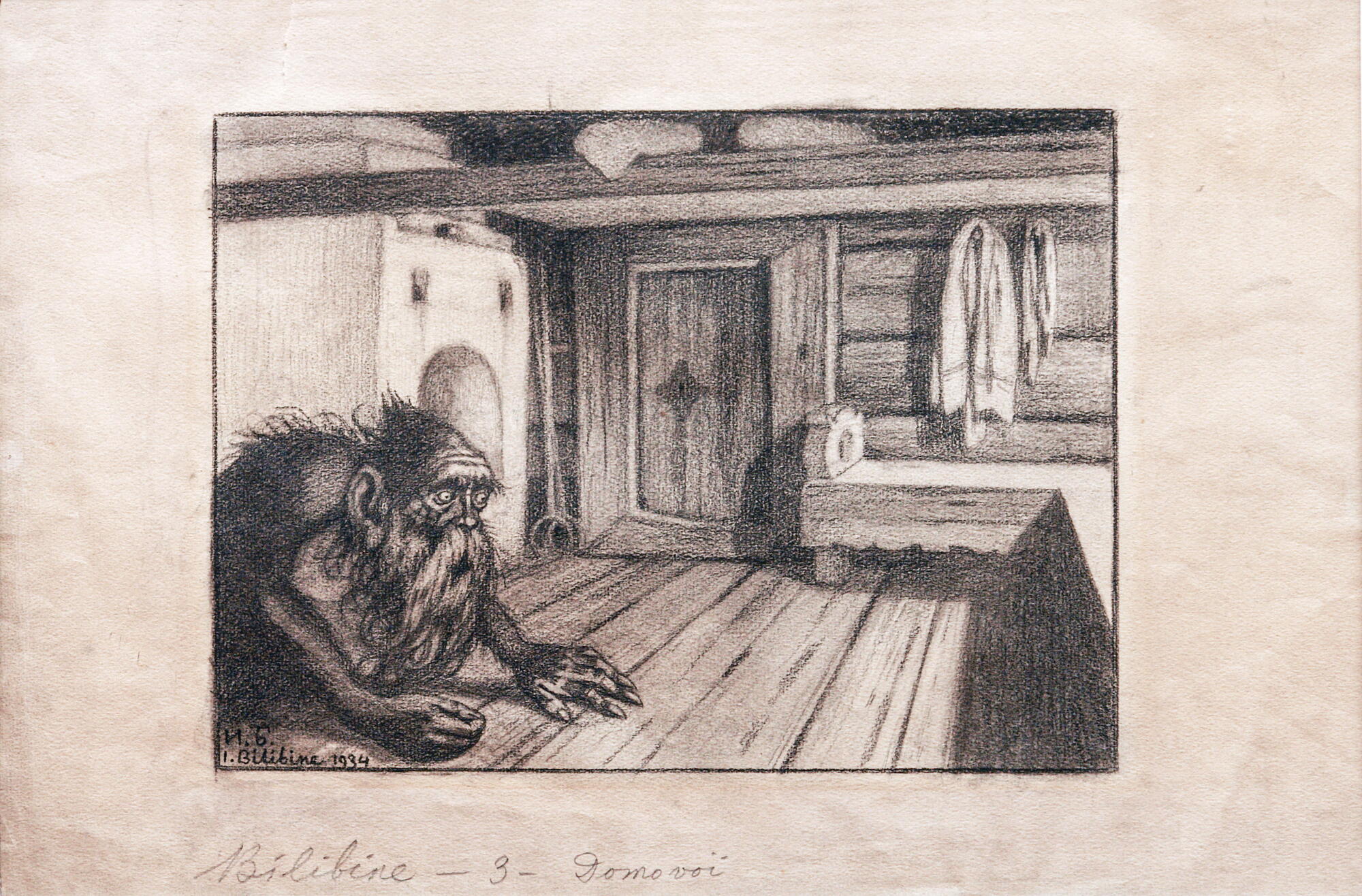

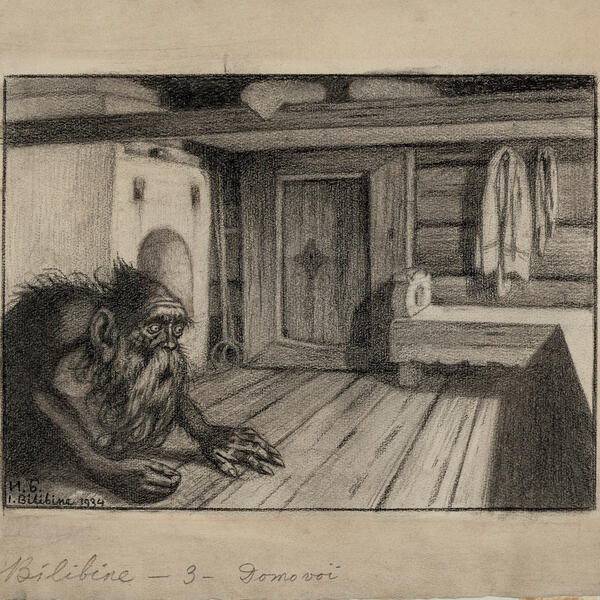

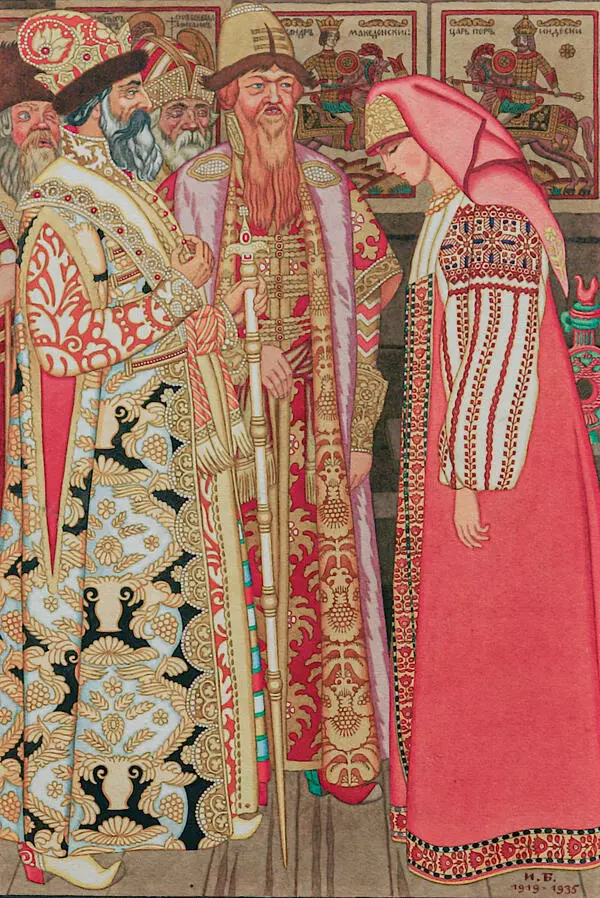

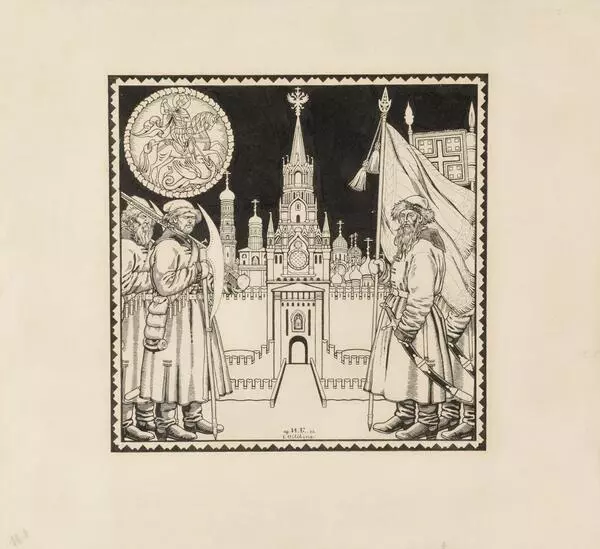

The “Domovoy” (a house spirit) is one of the illustrations by Ivan Yakovlevich Bilibin, created for the encyclopedia “World Mythology” printed by the French publishing house “Larousse”.

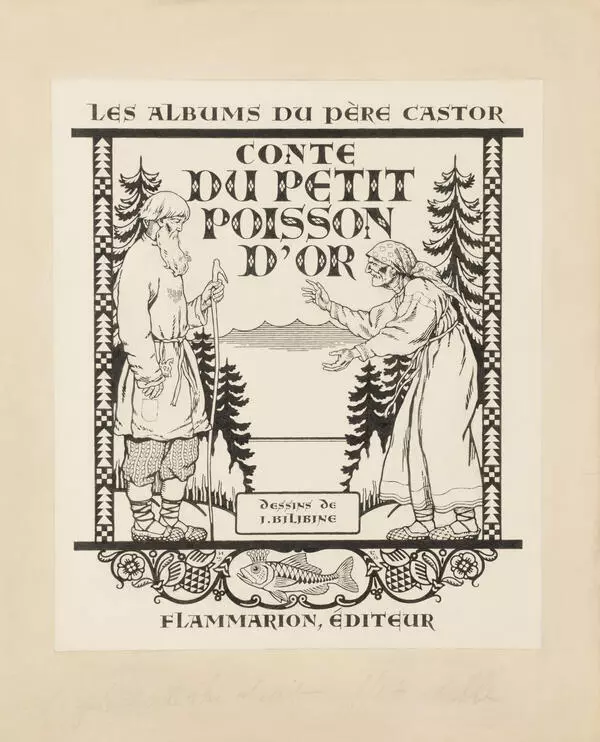

“I work a lot and in a variety of styles for different Parisian publishers, ” Bilibin wrote about his work in the first half of the 1930s, when once again he gave all his creativity and attention to graphic design of books. The main customers during this period were not the Russian emigrant publishing houses, but large Parisian firms. Bilibin’s works include illustrations for the collection of Russian folk tales Contes de l’isba (“Tales from a Hut”), French fairy tales by Jeanne Roche-Mazon Contes de la Couleuvre (“Tales of the Snake”), fairy tales by the brothers Grimm for the Paris publishing house Boivin et Cie. In 1934, the artist illustrated a section dedicated to Russian mythology in the encyclopedia “World Mythology” for the publishing house “Larousse”.

In Bilibin’s illustration, the domovoy appears as a shaggy old man of a short stature, exactly how people believed him to look like. His strength is evidenced by his huge hands. He crawls out from behind the stove when the owners are away. His gaze is wary, his eyebrows are frowned.

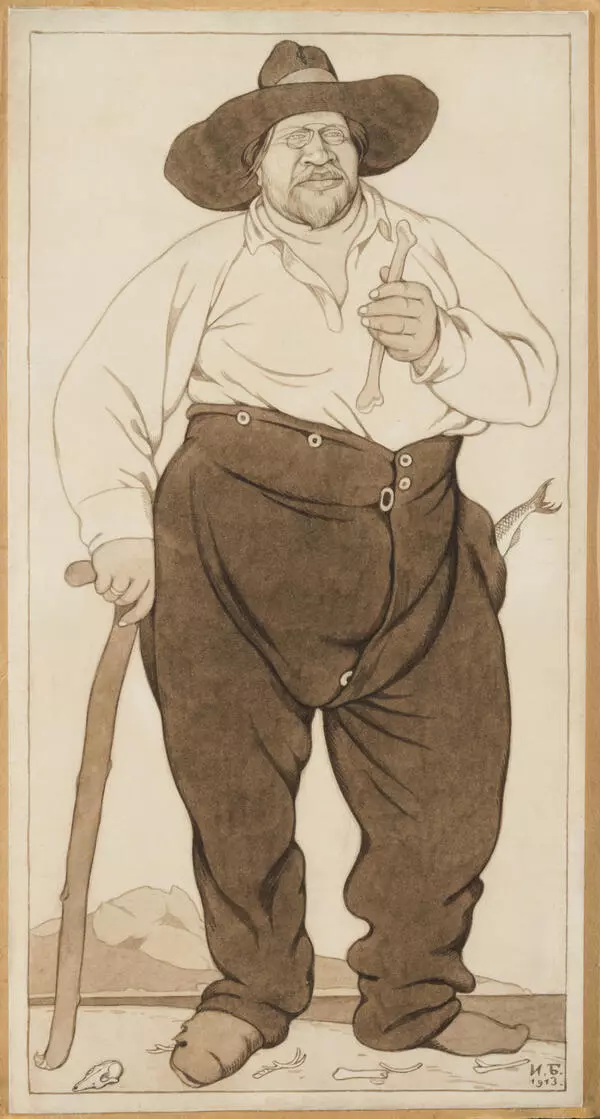

The expansion of the artist’s themes, his work on new types of publications, and designing various books contributed to the professional improvement of Bilibin, as an illustrator. However, his 1930s illustrations do not reach the level of the best Bilibin works of the previous decades. He had to work quickly which damaged the integrity of the Bilibin’s style: the artist began to repeat himself, the precision of his drawing bordered on dryness. The causes of this were not only external. Under the influence of the developing modern art, Bilibin had long had a desire to move away from the artistic canons of the past, to make expressive means more flexible and diverse. He aspired to it upon his return to his homeland in 1936.

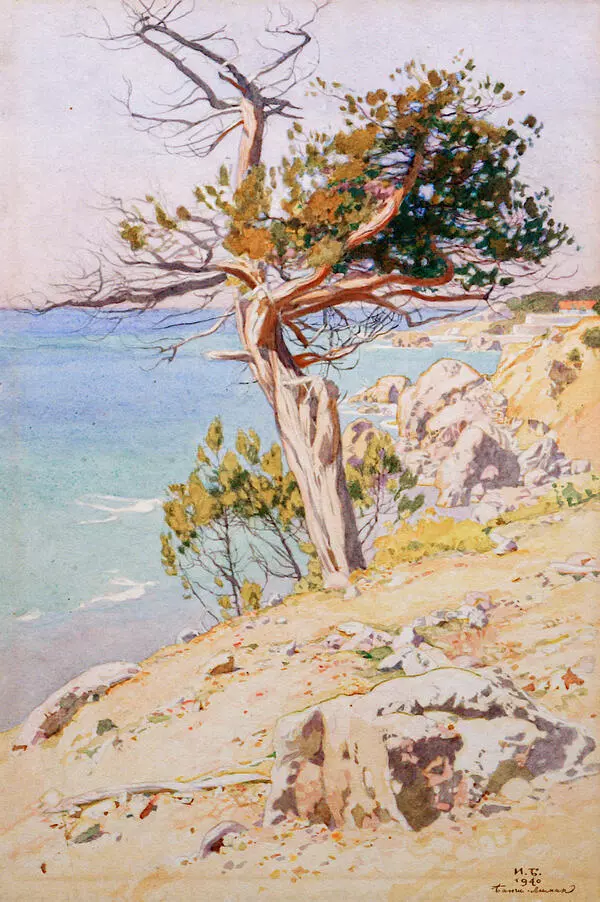

Bilibin goes from a predominantly contour drawing, in his own words, to a drawing “abundantly covered with a hatched fabric”, and sometimes to an almost freely hatched drawing. It was difficult for the artist to completely rebuild the long-established method, new works often turned out to be eclectic. However, Bilibin managed to subordinate impressions from nature to the laws of “strict” graphics of the early 20th century. Accepting the changes that had taken place in graphic art, the master nevertheless considered these laws to be fundamental and based his teaching system at the Graphic Department of the Institute of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture in Leningrad on these laws.

“I work a lot and in a variety of styles for different Parisian publishers, ” Bilibin wrote about his work in the first half of the 1930s, when once again he gave all his creativity and attention to graphic design of books. The main customers during this period were not the Russian emigrant publishing houses, but large Parisian firms. Bilibin’s works include illustrations for the collection of Russian folk tales Contes de l’isba (“Tales from a Hut”), French fairy tales by Jeanne Roche-Mazon Contes de la Couleuvre (“Tales of the Snake”), fairy tales by the brothers Grimm for the Paris publishing house Boivin et Cie. In 1934, the artist illustrated a section dedicated to Russian mythology in the encyclopedia “World Mythology” for the publishing house “Larousse”.

In Bilibin’s illustration, the domovoy appears as a shaggy old man of a short stature, exactly how people believed him to look like. His strength is evidenced by his huge hands. He crawls out from behind the stove when the owners are away. His gaze is wary, his eyebrows are frowned.

The expansion of the artist’s themes, his work on new types of publications, and designing various books contributed to the professional improvement of Bilibin, as an illustrator. However, his 1930s illustrations do not reach the level of the best Bilibin works of the previous decades. He had to work quickly which damaged the integrity of the Bilibin’s style: the artist began to repeat himself, the precision of his drawing bordered on dryness. The causes of this were not only external. Under the influence of the developing modern art, Bilibin had long had a desire to move away from the artistic canons of the past, to make expressive means more flexible and diverse. He aspired to it upon his return to his homeland in 1936.

Bilibin goes from a predominantly contour drawing, in his own words, to a drawing “abundantly covered with a hatched fabric”, and sometimes to an almost freely hatched drawing. It was difficult for the artist to completely rebuild the long-established method, new works often turned out to be eclectic. However, Bilibin managed to subordinate impressions from nature to the laws of “strict” graphics of the early 20th century. Accepting the changes that had taken place in graphic art, the master nevertheless considered these laws to be fundamental and based his teaching system at the Graphic Department of the Institute of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture in Leningrad on these laws.