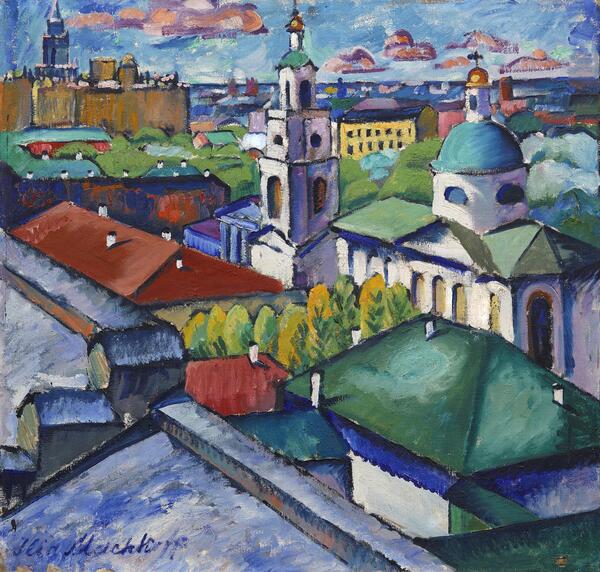

View of Moscow: Myasnitskiy District (1912-1913) is part of a group of landscapes created by Mashkov in a studio located in the attic of a high building in Kharitonyevskiy Lane. These are the views of Moscow that opened up through the windows of his studio.

The artists is not painting the capital, but a typical Russian city, with its everyday minutiae and solidity. But the author does not care about the life in the city, the life on the street: there are no people, and there is no movement or commotion in the landscapes, but only roofs, walls, and trees. This kind of superficial (both literally and figuratively) look at the subject of an image is more characteristic of a still life than a

landscape. The transformation of genre paintings into still lifes is typical for paintings done by artists in the ‘Jack of Diamonds’ association, to which Mashkov belonged. The desire for an objective grasp of reality led to artists increasingly rejecting the genre painting. Since the still life genre, in their opinion, eliminated the components of plot and narrative, and focused the viewer’s attention on the “simplest” and “intrinsic” qualities of the phenomena in the surrounding world, it was best suited to fulfill narrow, purely perfunctory tasks: revealing the texture or shape of an object, color patterns, and original figurative solutions. At the same time, the artists were not interested in the conceptual essence of the subject.

When working in other genres — portraits, landscapes — avant-garde artists from 1900 to the 1910s are fulfilling the same objectives and using the same stylistic techniques, and that is why all of their paintings — to varying degrees — resemble still lifes. This is also applicable to the View of Moscow: Myasnitskiy District. It is static, lacks a plot, and fulfills objectives that are purely perfunctory. But that does not mean that the painting itself is mechanical or empty. It is the other way around, and seems to shine with the concentrated lifeblood of a Russian city in the summer. The talent Mashkov has lies in the fact that by combining primitive, simplified forms and bright colors, he was able to convey, and even enhance, the living essence of objects, like the urban artistic folklore of the early twentieth century that he actively helped propagate. He draws on the signs and cheap, popular prints for the genuineness of the purely local color, which needs to correspond to real life but, at the same time, needs to be brighter, more intense, and more vibrant, since it is designed to unexpectedly capture someone’s attention, to astonish and entice a potential buyer or client. This is where the ‘inviting’ energy of color in Mashkov’s paintings stems from, which is combined with a Cezanne-like plasticity of spaces.

Everything in the landscape by Ilya Mashkov corresponds to the creative aesthetics of the artists in the “Jack of Diamonds” group — a close-up general view, rigorous painting style, intense, contrasting colors, strong-willed composure, and monumental static nature.

The artists is not painting the capital, but a typical Russian city, with its everyday minutiae and solidity. But the author does not care about the life in the city, the life on the street: there are no people, and there is no movement or commotion in the landscapes, but only roofs, walls, and trees. This kind of superficial (both literally and figuratively) look at the subject of an image is more characteristic of a still life than a

landscape. The transformation of genre paintings into still lifes is typical for paintings done by artists in the ‘Jack of Diamonds’ association, to which Mashkov belonged. The desire for an objective grasp of reality led to artists increasingly rejecting the genre painting. Since the still life genre, in their opinion, eliminated the components of plot and narrative, and focused the viewer’s attention on the “simplest” and “intrinsic” qualities of the phenomena in the surrounding world, it was best suited to fulfill narrow, purely perfunctory tasks: revealing the texture or shape of an object, color patterns, and original figurative solutions. At the same time, the artists were not interested in the conceptual essence of the subject.

When working in other genres — portraits, landscapes — avant-garde artists from 1900 to the 1910s are fulfilling the same objectives and using the same stylistic techniques, and that is why all of their paintings — to varying degrees — resemble still lifes. This is also applicable to the View of Moscow: Myasnitskiy District. It is static, lacks a plot, and fulfills objectives that are purely perfunctory. But that does not mean that the painting itself is mechanical or empty. It is the other way around, and seems to shine with the concentrated lifeblood of a Russian city in the summer. The talent Mashkov has lies in the fact that by combining primitive, simplified forms and bright colors, he was able to convey, and even enhance, the living essence of objects, like the urban artistic folklore of the early twentieth century that he actively helped propagate. He draws on the signs and cheap, popular prints for the genuineness of the purely local color, which needs to correspond to real life but, at the same time, needs to be brighter, more intense, and more vibrant, since it is designed to unexpectedly capture someone’s attention, to astonish and entice a potential buyer or client. This is where the ‘inviting’ energy of color in Mashkov’s paintings stems from, which is combined with a Cezanne-like plasticity of spaces.

Everything in the landscape by Ilya Mashkov corresponds to the creative aesthetics of the artists in the “Jack of Diamonds” group — a close-up general view, rigorous painting style, intense, contrasting colors, strong-willed composure, and monumental static nature.

“Pithiness and a bird”s-eye perspective represented one of the permanent methods used by the “Jack of Diamonds” group, ’ recalled Aristarkh Lentulov, one of the founders of the artists’ association.