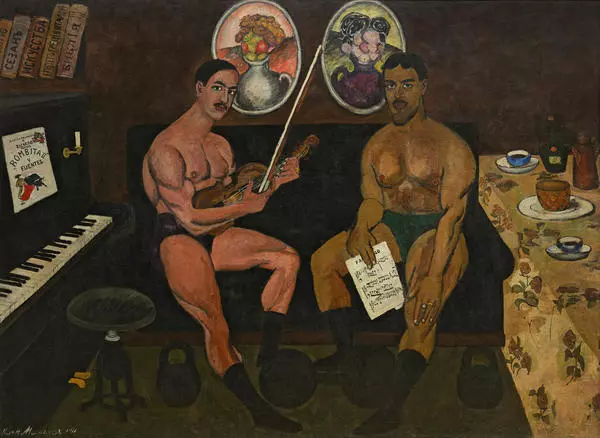

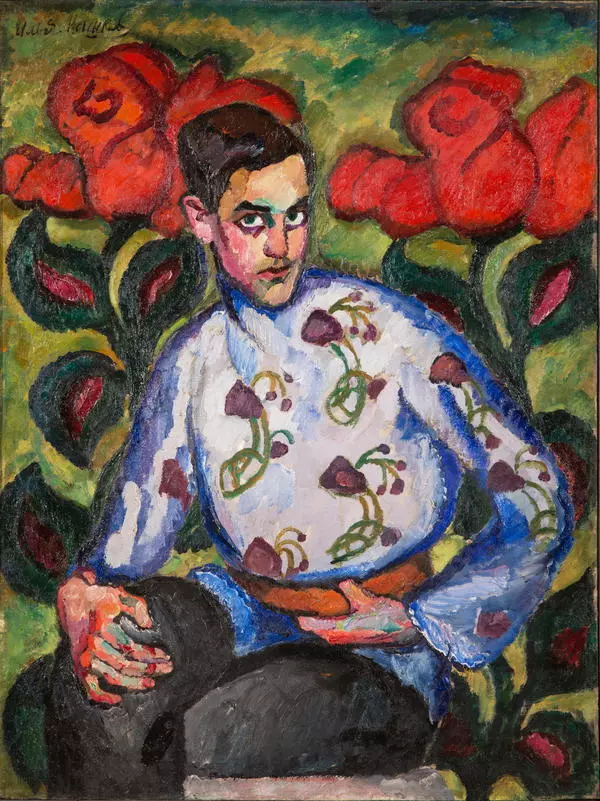

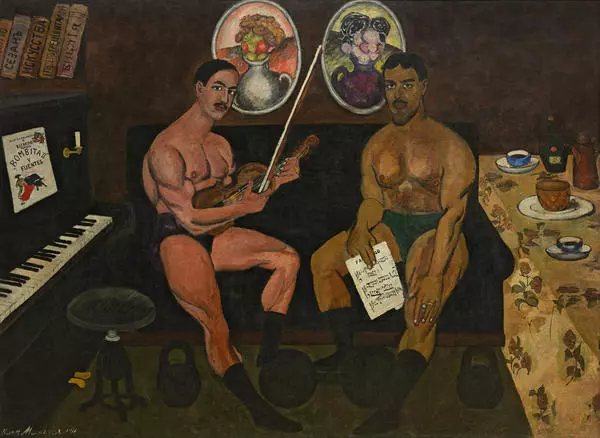

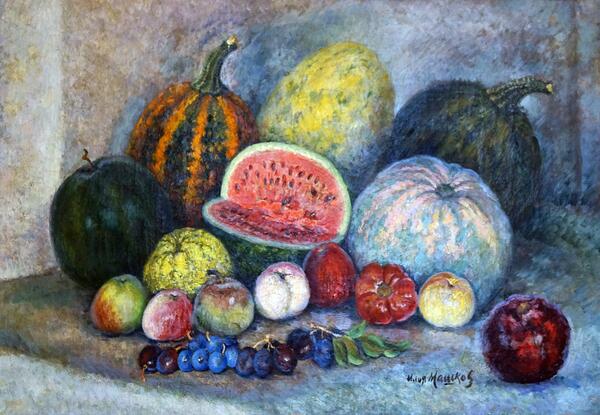

Ilya Ivanovich Mashkov is one of the most brilliant painters in that early Russian avant-garde movement that appeared in the early 1910s under the boldly provocative name ‘Jack of Diamonds’. In this depiction of Shimanovskiy, the aspiration to achieve ostentation is clearly noticeable. Unlike his portraits of the mid-1910s, the painter does not emphasize depth, but rather ‘flattens’ the space. The plan is enlarged, the figure and accessories are viewed with increased fixedness.

Mashkov is concerned with a specially selecting those things that have memorable personalities: a decorative column of Karelian birch, mahogany furniture, a Zhostovo-style painted tray, an elegant bottle, and a red copper tea urn with a teapot. Shimanovskiy’s face, interpreted with naturalistic rigidity, reveals a difficult, complex character. There is some tension in how the figure is sitting, in the position of his hands, and in his whole appearance. And this is, perhaps, all that can be said about him. The still life accessories essentially do not add anything to the psychological portrait. From all appearances, this portrait was originally intended to be exactly like this. Drawings that came before it have been preserved. One of those even defined the pose of the model, his environment with the objects, and the general solution for the composition. Apparently, portraits were more difficult for the artist than landscapes and still lifes, and required long periods of thought and some preliminary preparation: he did graphic sketches for most of them.

Mashkov is concerned with a specially selecting those things that have memorable personalities: a decorative column of Karelian birch, mahogany furniture, a Zhostovo-style painted tray, an elegant bottle, and a red copper tea urn with a teapot. Shimanovskiy’s face, interpreted with naturalistic rigidity, reveals a difficult, complex character. There is some tension in how the figure is sitting, in the position of his hands, and in his whole appearance. And this is, perhaps, all that can be said about him. The still life accessories essentially do not add anything to the psychological portrait. From all appearances, this portrait was originally intended to be exactly like this. Drawings that came before it have been preserved. One of those even defined the pose of the model, his environment with the objects, and the general solution for the composition. Apparently, portraits were more difficult for the artist than landscapes and still lifes, and required long periods of thought and some preliminary preparation: he did graphic sketches for most of them.

It is a matter of interest what role the most traditional of those fulfills for a typical “Jack of Diamonds” picture in the how the accessories spectacularly play off each other. First of all, the Zhostovo-style painted tray. In Mashkov’s earlier works as well, the trays did not act in keeping with their utilitarian functionality, but it is as if they are ‘posed’, turned toward the viewer in a vertical position, like a kind of ‘picture within a picture’. It was correctly noted: ‘the less Mashkov was interested in the tray as a utensil, the more importance it acquired as a figurative excerpt, as an example of “tray style”. In the early 1910s, painting trays helped adjust Mashkov’s personal stylistics. And not only in still lifes. Back in 1911, Maximilian Voloshin noted this desire on the part of ‘Jack of Diamonds’ painters to interpret the appearance of the model in a still life: ‘They tried to simplify and generalize the human face, in basic planes and outlines, in exactly the same way that they would simplify an apple, pumpkin, watering can, pineapple, or piece of bread.’