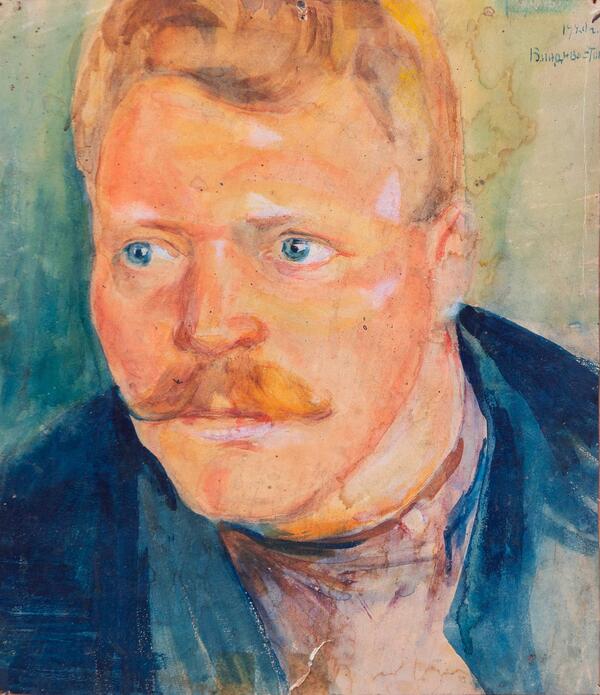

David Davidovich Burlyuk, a poet and artist, was a pioneer of the Russian avant-garde and futurism. He enthusiastically promoted the new art, and his works are easily recognizable by the unique painting style and intricate interplay of colors.

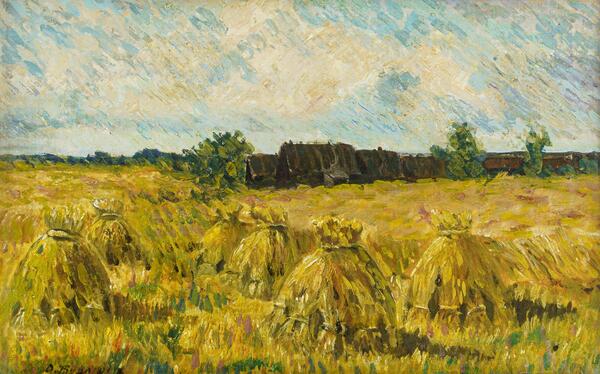

The Terrace dates to 1917, when Burlyuk lived in the village of Iglino near Ufa with his wife and children. The artist created a lot of paintings in that place, including his famous Bashkir landscapes. The artist himself counted the 200 plus paintings created in that period among his best artworks.

The Terrace is not exactly a landscape: the beauty of the nature is seen by the artist from inside the room. In this work, the artist met a hard and unusual artistic challenge — the terrace appears illuminated, but the viewer sees no direct source of light, which remains outside the painting’s boundary.

The very texture of the painting creates an impression of the abundance of light: bright and rich colors, multicolor shades, and broad strokes. The sky and the earth seem molded like sculptures, and the full image appears three-dimensional and vivid.

The style of the painting represents a Russian version of pictorial impressionism. The absolutely decorative color scheme and vibrating impasto strokes make the natural environment depicted on the canvas amazingly light and aerial. At first glance, the strokes might seem overly broad and rough, but with all that, the canvas looks wonderfully realistic and harmonious.

Like many other Burlyuk’s works of the ‘Bashkir’ period, the Terrace represents a well-balanced combination of artistic ‘tradition’ and ‘innovation’. David Burlyuk enthusiastically supported experiments in art, but always said that experimenting without excellent knowledge of academic painting was impossible.

The artist proved the point in his paintings by successful use of realistic and impressionistic technique along with futuristic ‘shifts, and “broken lines” typical of cubism, as well as pronounced contour lines reminiscent of Germen expressionism and the old Russian painting tradition.

Burlyuk’s ‘anything-goes’ attitude was noted by one of his first biographers, Erich Fedorovich Hollerbach: ‘Some perfectionist could “catch” the artist on blatant inconsistencies’. However, these inconsistencies look most agreeable in the paintings of the renowned master.

The Terrace dates to 1917, when Burlyuk lived in the village of Iglino near Ufa with his wife and children. The artist created a lot of paintings in that place, including his famous Bashkir landscapes. The artist himself counted the 200 plus paintings created in that period among his best artworks.

The Terrace is not exactly a landscape: the beauty of the nature is seen by the artist from inside the room. In this work, the artist met a hard and unusual artistic challenge — the terrace appears illuminated, but the viewer sees no direct source of light, which remains outside the painting’s boundary.

The very texture of the painting creates an impression of the abundance of light: bright and rich colors, multicolor shades, and broad strokes. The sky and the earth seem molded like sculptures, and the full image appears three-dimensional and vivid.

The style of the painting represents a Russian version of pictorial impressionism. The absolutely decorative color scheme and vibrating impasto strokes make the natural environment depicted on the canvas amazingly light and aerial. At first glance, the strokes might seem overly broad and rough, but with all that, the canvas looks wonderfully realistic and harmonious.

Like many other Burlyuk’s works of the ‘Bashkir’ period, the Terrace represents a well-balanced combination of artistic ‘tradition’ and ‘innovation’. David Burlyuk enthusiastically supported experiments in art, but always said that experimenting without excellent knowledge of academic painting was impossible.

The artist proved the point in his paintings by successful use of realistic and impressionistic technique along with futuristic ‘shifts, and “broken lines” typical of cubism, as well as pronounced contour lines reminiscent of Germen expressionism and the old Russian painting tradition.

Burlyuk’s ‘anything-goes’ attitude was noted by one of his first biographers, Erich Fedorovich Hollerbach: ‘Some perfectionist could “catch” the artist on blatant inconsistencies’. However, these inconsistencies look most agreeable in the paintings of the renowned master.