Now we may freely talk about David Davidovich Burlyuk, but until the very early 1990s, his personality and artistic heritage were ‘blind spots’ in Russia. The reason is trivial: emigration to Japan, and then to America where he spent most of his life.

The only place where the memory of the artist has always been treasured is the city of Ufa. Even in the mid of the Cold War, the M.V. Nesterov Art Museum exhibited several of his works, and today the museum dedicates a full room to his art.

The father of Russian futurism moved to Bashkiria with his family in the spring of 1915 and spent three happy years here. In 1914, Burlyuk and his true friend Vladimir Mayakovsky were expelled from the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture for their passionate interest in the ‘harmful and dangerous’ art style. Mayakovsky soon found himself in the frontline. Burlyuk was concerned that he might be conscripted as well even though he had lost his eye in a kids’ fight and could hardly be enlisted. Bashkiria became his second motherland that left indelible mark in his soul. He always remembered it with love and a strong feeling of nostalgia.

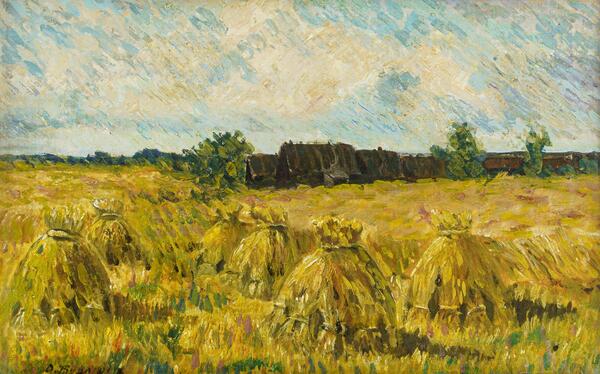

Working as a haymaker for the Russian Army, David Burlyuk used burlap sacks for canvasses. That is why the 200 paintings made by the artist in Bashkiria are distinguished by a remarkable relief texture.

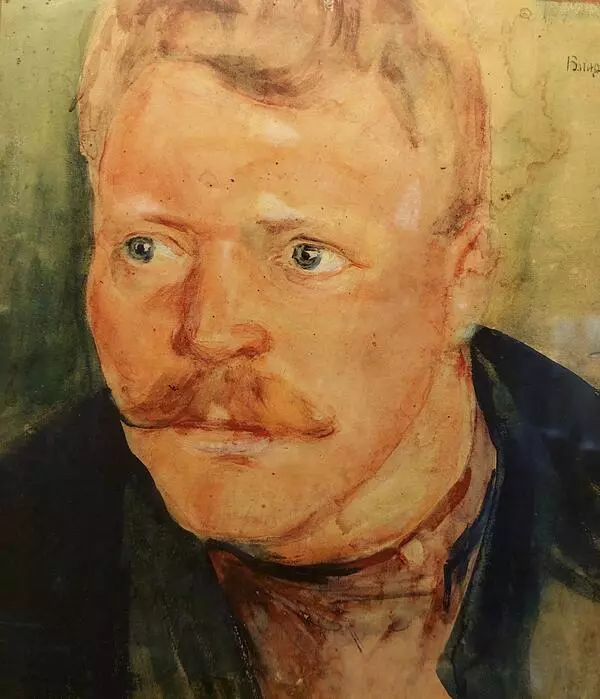

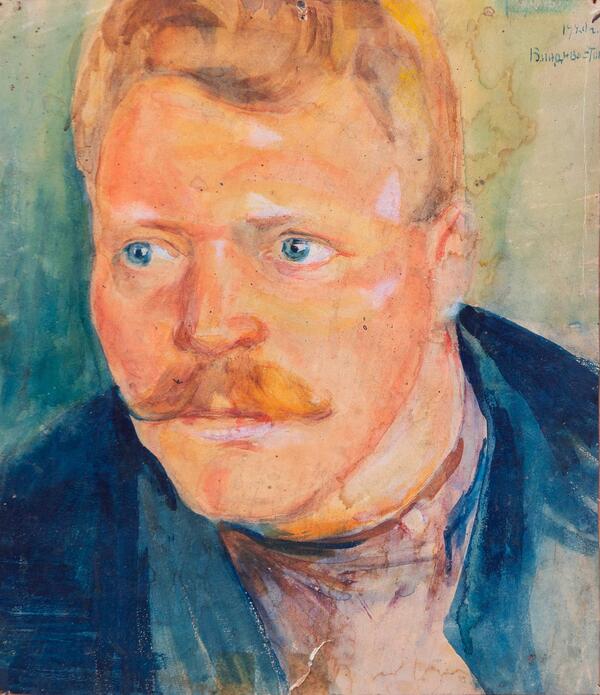

Fascinated by the character types and expressive faces of local residents the artist used his only eye to understand their inner world and get to the essence of their personalities. Notably, most of his portraits fail to reveal any trace of futurism so well loved by Burlyuk.

They look more like quality plain-air paintings with objects seamlessly blended into the environment. The canvasses are full of life. The focus is on general perception rather than likeness in every detail. A sophisticated mosaic of thick strokes born by a unique interplay of light and shade is an effective impressionistic technique used to add dynamics to the image.

The images of multiple local residents attract the viewer by their warmth, intrinsic sincerity, and naive charm, and delight by the richness and brilliancy of color. The thick impasto painting with its coloristic vigor, the choice of contrasting and at the same time harmonious colors adds to the impression of three-dimensional perspectives.

In Ufa, Burlyuk encouraged and supported interest and close attention to specific details of indigenous life among his local colleagues. The young painters followed Burlyuk to the nearest ravines to make sketches and sometimes would capture the same motive independently of each other.

Burlyuk’s realistic portraits were the first visual artworks in Bashkortostan to create an image of the national character types. David Burlyuk’s contribution to the development of the Bashkir school of painting and its artistic self-identification is fairly significant.

The only place where the memory of the artist has always been treasured is the city of Ufa. Even in the mid of the Cold War, the M.V. Nesterov Art Museum exhibited several of his works, and today the museum dedicates a full room to his art.

The father of Russian futurism moved to Bashkiria with his family in the spring of 1915 and spent three happy years here. In 1914, Burlyuk and his true friend Vladimir Mayakovsky were expelled from the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture for their passionate interest in the ‘harmful and dangerous’ art style. Mayakovsky soon found himself in the frontline. Burlyuk was concerned that he might be conscripted as well even though he had lost his eye in a kids’ fight and could hardly be enlisted. Bashkiria became his second motherland that left indelible mark in his soul. He always remembered it with love and a strong feeling of nostalgia.

Working as a haymaker for the Russian Army, David Burlyuk used burlap sacks for canvasses. That is why the 200 paintings made by the artist in Bashkiria are distinguished by a remarkable relief texture.

Fascinated by the character types and expressive faces of local residents the artist used his only eye to understand their inner world and get to the essence of their personalities. Notably, most of his portraits fail to reveal any trace of futurism so well loved by Burlyuk.

They look more like quality plain-air paintings with objects seamlessly blended into the environment. The canvasses are full of life. The focus is on general perception rather than likeness in every detail. A sophisticated mosaic of thick strokes born by a unique interplay of light and shade is an effective impressionistic technique used to add dynamics to the image.

The images of multiple local residents attract the viewer by their warmth, intrinsic sincerity, and naive charm, and delight by the richness and brilliancy of color. The thick impasto painting with its coloristic vigor, the choice of contrasting and at the same time harmonious colors adds to the impression of three-dimensional perspectives.

In Ufa, Burlyuk encouraged and supported interest and close attention to specific details of indigenous life among his local colleagues. The young painters followed Burlyuk to the nearest ravines to make sketches and sometimes would capture the same motive independently of each other.

Burlyuk’s realistic portraits were the first visual artworks in Bashkortostan to create an image of the national character types. David Burlyuk’s contribution to the development of the Bashkir school of painting and its artistic self-identification is fairly significant.