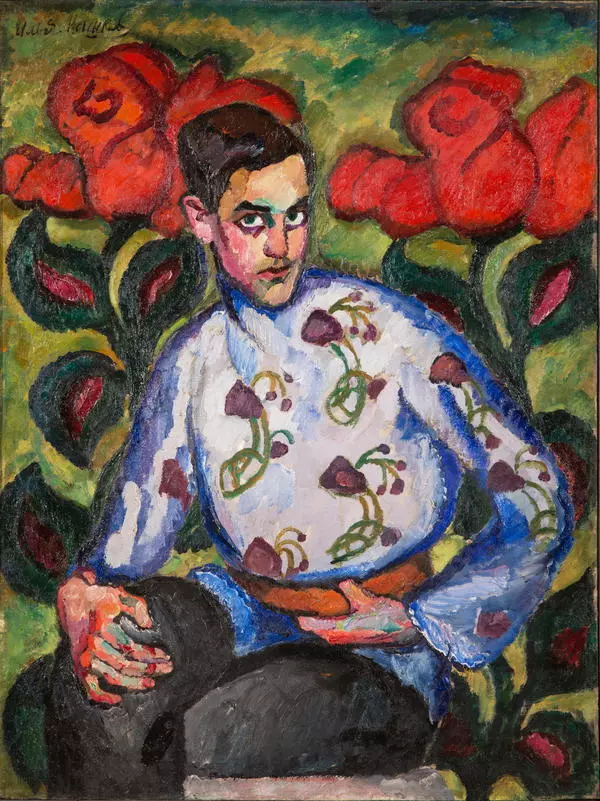

Ilya Mashkov painted a thematic still-life ‘Soviet Breads’ in 1936 in two versions. One of them is displayed at the exposition of the Volgograd Museum, and the other is in the State Museum of Fine Arts of the Republic of Tatarstan in Kazan.

Mashkov had addressed this topic before. The Russian Museum houses his work called ‘Breads. Still Life’ created in 1913. And the Tretyakov Gallery houses a picture named ‘Moscow Food: Breads’, dated 1924.

The prototype for the still life ‘Soviet Breads’ was the shop street signs that bakers hung outside their shops or in the trading rows.

The painting ‘Soviet Breads’ symbolizes the abundance, wealth, and power of the new Soviet state. The canvas itself is packed with huge quantities of baked goods, that is loafs, pretzels, round cracknels, cakes and pastries. In a country that had just survived a terrible famine, such a still life could only be compared to an icon.

The researchers consider the soviet famine of 1932–1933 as a consequence of the forced grain procurement of 1929 and collectivization, which created a shortage of food in the countryside. Accelerated industrialization required funds, and the main money resources came from the grain export. Peasant farms were given impossible grain delivery targets.

The still life is characterized by emphasized decorative, hyper-realistic theme. Mashkov painted this work with small neat strokes. The coloring of the painting is restrained, unlike the master’s earlier works, in which he experimented with color and turned to fauvism and cezannism.

The fauvism style was characterized by the dynamic of the drawing, spontaneity, bright and pure colors, and the juxtaposition of contrasting planes. The works in the cezannism style, in turn, were characterized by contrasting colors, simplified geometric shapes, the combination of several view points on objects.

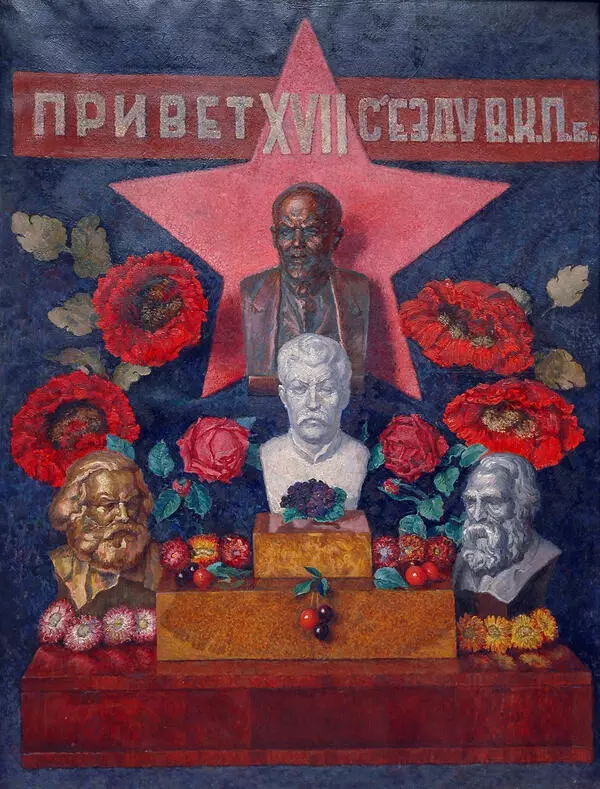

The anthem for happy, grandiose and large-scale Soviet life in the 1930s became almost an independent painting genre. However, for all the seriousness of the subject and the solemnity of the depicted “Soviet Breads” leaves the impression of a joyful spectacle.

Art historians call this painting a myth, a naive and sincere canvas that cannot be considered as a government order.

Mashkov had addressed this topic before. The Russian Museum houses his work called ‘Breads. Still Life’ created in 1913. And the Tretyakov Gallery houses a picture named ‘Moscow Food: Breads’, dated 1924.

The prototype for the still life ‘Soviet Breads’ was the shop street signs that bakers hung outside their shops or in the trading rows.

The painting ‘Soviet Breads’ symbolizes the abundance, wealth, and power of the new Soviet state. The canvas itself is packed with huge quantities of baked goods, that is loafs, pretzels, round cracknels, cakes and pastries. In a country that had just survived a terrible famine, such a still life could only be compared to an icon.

The researchers consider the soviet famine of 1932–1933 as a consequence of the forced grain procurement of 1929 and collectivization, which created a shortage of food in the countryside. Accelerated industrialization required funds, and the main money resources came from the grain export. Peasant farms were given impossible grain delivery targets.

The still life is characterized by emphasized decorative, hyper-realistic theme. Mashkov painted this work with small neat strokes. The coloring of the painting is restrained, unlike the master’s earlier works, in which he experimented with color and turned to fauvism and cezannism.

The fauvism style was characterized by the dynamic of the drawing, spontaneity, bright and pure colors, and the juxtaposition of contrasting planes. The works in the cezannism style, in turn, were characterized by contrasting colors, simplified geometric shapes, the combination of several view points on objects.

The anthem for happy, grandiose and large-scale Soviet life in the 1930s became almost an independent painting genre. However, for all the seriousness of the subject and the solemnity of the depicted “Soviet Breads” leaves the impression of a joyful spectacle.

Art historians call this painting a myth, a naive and sincere canvas that cannot be considered as a government order.