Kazimir Malevich was the oldest of nine children in the family of a Polish nobleman Severin Malevich and Ludwiga Galinovskaya. The artist was born in Kiev and spent his childhood in small Ukrainian villages. Malevich did not receive a systemic art education but studied in private schools and studios.

In 1907 Malevich moved to Moscow where he met artist Mikhail Larionov, one of the founders of the Russian avant-garde. Malevich took part in several exhibitions organized by Larionov including the Knave of Diamonds.

In the 1910’s Larionov broke his ties with members of the Knave of Diamonds association and established an art group under a provocative name of Donkey’s Tail. The name referred to the scandal in Paris Salon des Independents, where a group of mystifiers exhibited in 1910 the abstract painting that was in fact ‘painted’ by a donkey’s tail. The artists from the Donkey’s Tail association promoted primitive painting, developed the style of signboard, popular print, children’s drawing.

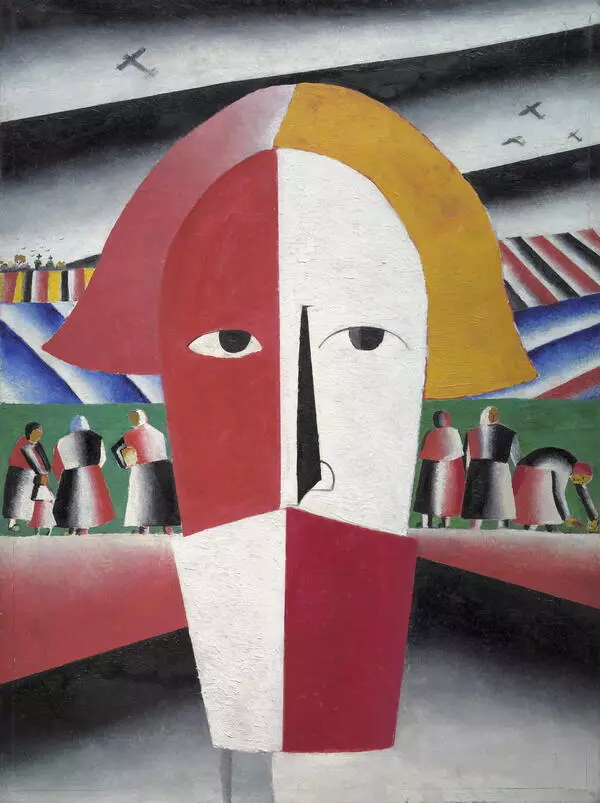

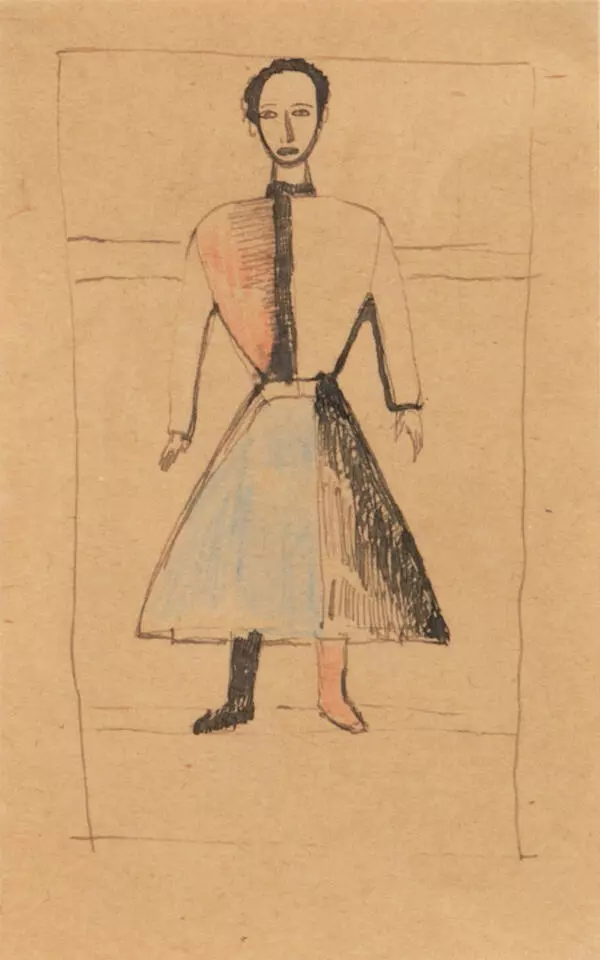

Kazimir Malevich also joined the Donkey’s Tail association. At the 1912 exhibition he presented 20 neo-primitive paintings. The painting Harvester from the collection of Astrakhan Art Gallery is also painted in that style.

Malevich purposefully enlarged and distorted the figure of the peasant woman to give it more expressiveness and fit it accurately in the canvas square. The bulky and massive figure of the harvester emphasizes her connection to the earth element and pristine strength.

In the 1910’s Malevich was also involved in icon — he believed it to be the ultimate stage of “peasant art”. In the Harvester he used the two-dimensional composition of an icon, special color scheme resembling icon painting and inverted perspective where objects further away from the viewer are depicted larger.

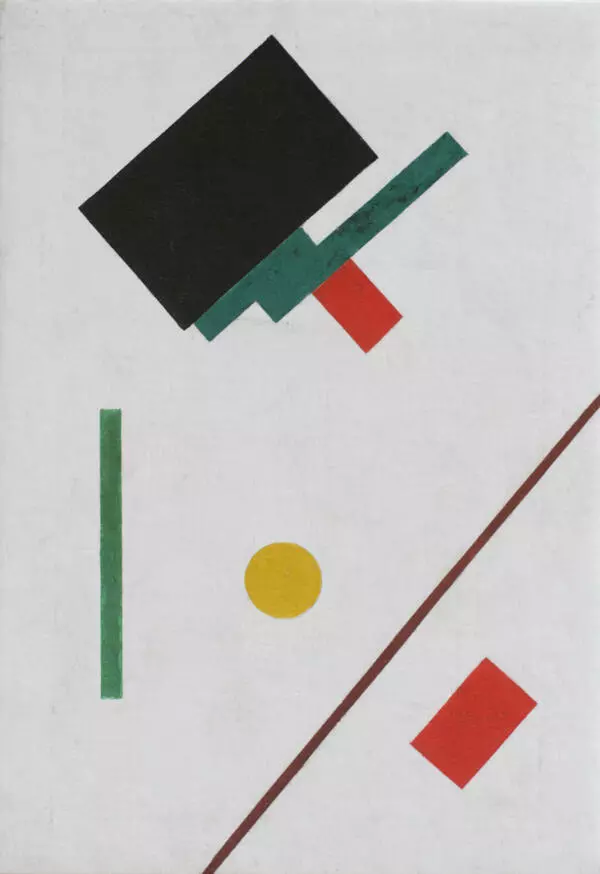

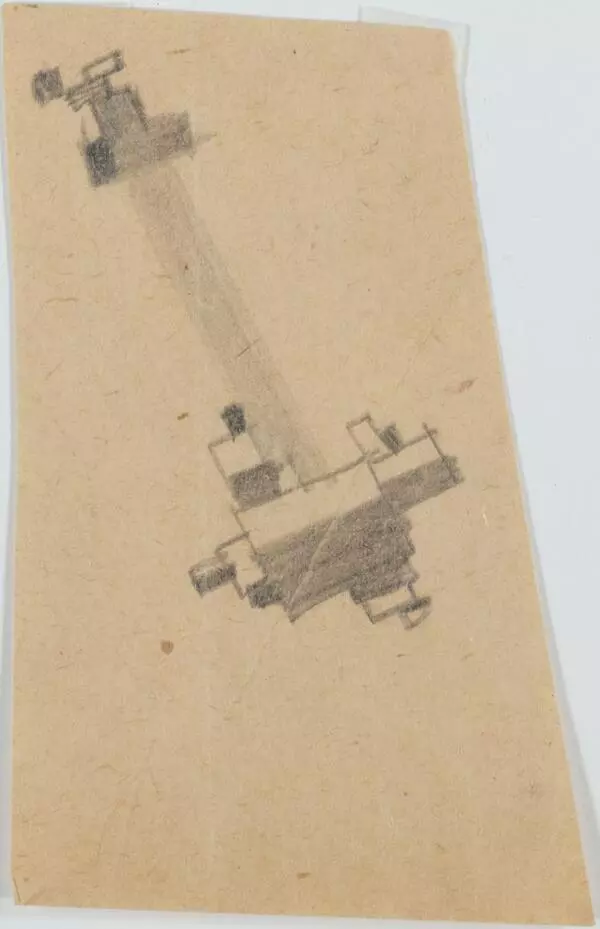

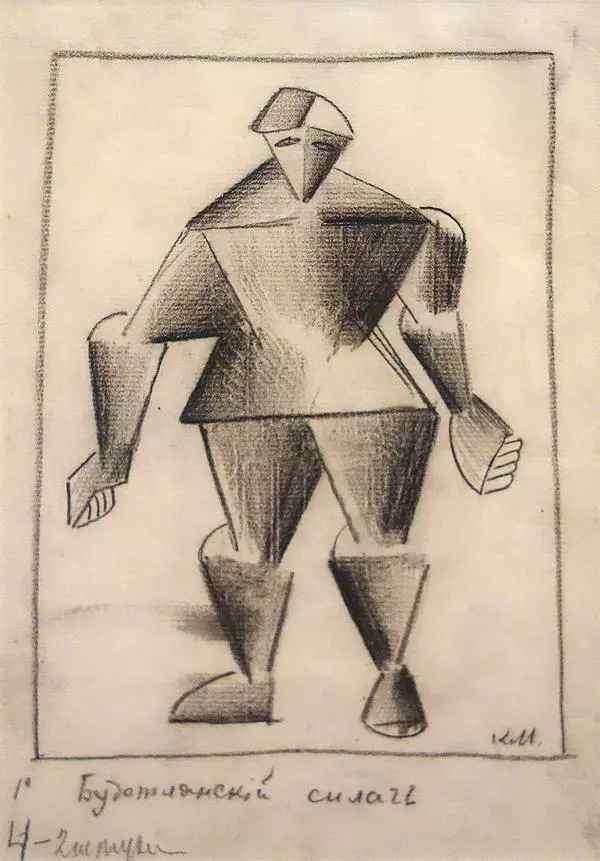

Soon Malevich switched from neo-primitivism to abstraction. His new views — the idea of suprematism (from the Latin “supremus” - “the highest”) — reflected the artist’s belief in the victory over thingness, over the three-dimensional space.

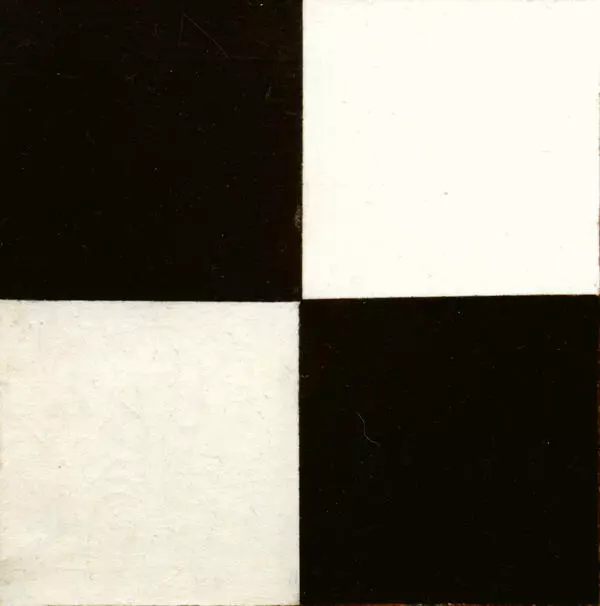

Malevich saw in geometrical shapes ‘the origin of all potential’ of the new art. In his famous triptych Black Square, Black Circle and Black Cross he used only the basic figures that he turned into art formulas with sacral sense. To emphasize it, at the Last Futuristic Exhibition of Paintings 0.10 of 1915 Malevich hung the Black Square in the right ‘icon corner’ — as an icon, the symbol of new time and new art.

In 1907 Malevich moved to Moscow where he met artist Mikhail Larionov, one of the founders of the Russian avant-garde. Malevich took part in several exhibitions organized by Larionov including the Knave of Diamonds.

In the 1910’s Larionov broke his ties with members of the Knave of Diamonds association and established an art group under a provocative name of Donkey’s Tail. The name referred to the scandal in Paris Salon des Independents, where a group of mystifiers exhibited in 1910 the abstract painting that was in fact ‘painted’ by a donkey’s tail. The artists from the Donkey’s Tail association promoted primitive painting, developed the style of signboard, popular print, children’s drawing.

Kazimir Malevich also joined the Donkey’s Tail association. At the 1912 exhibition he presented 20 neo-primitive paintings. The painting Harvester from the collection of Astrakhan Art Gallery is also painted in that style.

Malevich purposefully enlarged and distorted the figure of the peasant woman to give it more expressiveness and fit it accurately in the canvas square. The bulky and massive figure of the harvester emphasizes her connection to the earth element and pristine strength.

In the 1910’s Malevich was also involved in icon — he believed it to be the ultimate stage of “peasant art”. In the Harvester he used the two-dimensional composition of an icon, special color scheme resembling icon painting and inverted perspective where objects further away from the viewer are depicted larger.

Soon Malevich switched from neo-primitivism to abstraction. His new views — the idea of suprematism (from the Latin “supremus” - “the highest”) — reflected the artist’s belief in the victory over thingness, over the three-dimensional space.

Malevich saw in geometrical shapes ‘the origin of all potential’ of the new art. In his famous triptych Black Square, Black Circle and Black Cross he used only the basic figures that he turned into art formulas with sacral sense. To emphasize it, at the Last Futuristic Exhibition of Paintings 0.10 of 1915 Malevich hung the Black Square in the right ‘icon corner’ — as an icon, the symbol of new time and new art.