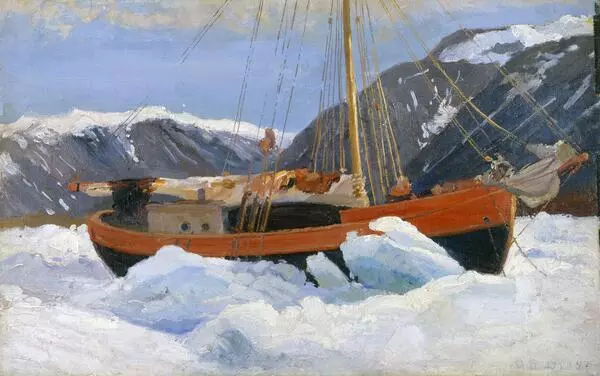

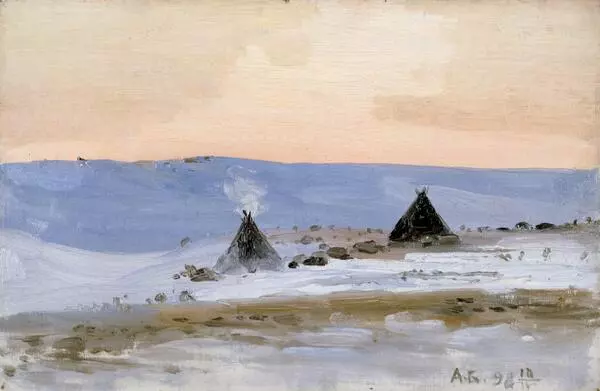

During his journeys across the tundra, Alexander Borisov happened to see people living in extreme poverty. The picture Poor Samoyed’s Household under a Boat in the Tundra shows such a type of lifestyle.

An upturned boat served as a dwelling place for poor Nenets people who didn’t have enough reindeer skins to build a chum. During summer, poor Nenets families took shelter under boats; when winter came, they moved to chums of their wealthier peers. Some of those chums were so big that people could walk there freely, Borisov recollects.

The artist gave a lot of thought to the living conditions of the Nenets people. He wrote: “Life in the tundra is quite hard for everyone. And even more bitter it must be for those Samoyeds who don”t have chums and are compelled to live under boats — at least during the summer. During the winter, other Samoyeds take pity on them and let them live in their chums. And yet, despite all the hardships, there are many fashionable women in the tundra. Here is a scene: the Samoyed house-father has left for fishing or hunting, so that his wife and children won”t starve to death. But his Samoyed wife doesn”t care a bit. More than anything, she is interested in a piece of red cloth. She has carefully produced it out of her sack and has lost herself in it. On the bottom of her malitsa coat, she is cutting and embroidering a colourful Samoyed pattern to attract her slant-eyed Samoyed husband. Beside her, in front of the boat dwelling, simple Samoyed belongings lie: a pot to cook fish and meat in, a kettle for tea that Samoyeds can”t live a single day without. A red, coffin-shaped box with butter for the most desirable guests; a piece of bread that must be as old as that Samoyed. In the same box, there is an idol wrapped in a worn cloth, often with an Orthodox icon.’

In spite of the dire need, a poor Nenets would never dare to engage in thievery and would rather die than steal anything, Borisov observes.

An upturned boat served as a dwelling place for poor Nenets people who didn’t have enough reindeer skins to build a chum. During summer, poor Nenets families took shelter under boats; when winter came, they moved to chums of their wealthier peers. Some of those chums were so big that people could walk there freely, Borisov recollects.

The artist gave a lot of thought to the living conditions of the Nenets people. He wrote: “Life in the tundra is quite hard for everyone. And even more bitter it must be for those Samoyeds who don”t have chums and are compelled to live under boats — at least during the summer. During the winter, other Samoyeds take pity on them and let them live in their chums. And yet, despite all the hardships, there are many fashionable women in the tundra. Here is a scene: the Samoyed house-father has left for fishing or hunting, so that his wife and children won”t starve to death. But his Samoyed wife doesn”t care a bit. More than anything, she is interested in a piece of red cloth. She has carefully produced it out of her sack and has lost herself in it. On the bottom of her malitsa coat, she is cutting and embroidering a colourful Samoyed pattern to attract her slant-eyed Samoyed husband. Beside her, in front of the boat dwelling, simple Samoyed belongings lie: a pot to cook fish and meat in, a kettle for tea that Samoyeds can”t live a single day without. A red, coffin-shaped box with butter for the most desirable guests; a piece of bread that must be as old as that Samoyed. In the same box, there is an idol wrapped in a worn cloth, often with an Orthodox icon.’

In spite of the dire need, a poor Nenets would never dare to engage in thievery and would rather die than steal anything, Borisov observes.