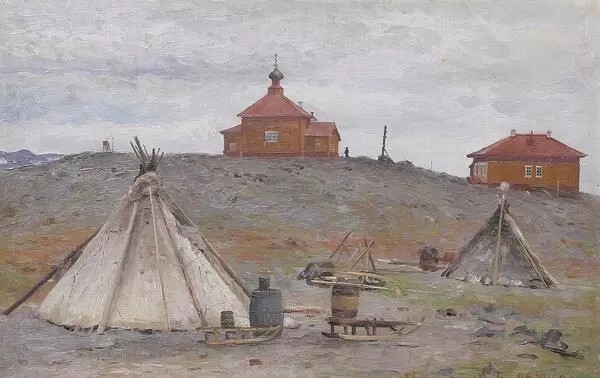

In the spring and summer of 1898, the dwellers of the Bolshezemelskaya Tundra witnessed a strange sight: a newcomer, apparently no different from Russian traders that often appeared in the Far North, carrying out weird activities. During breaks on the way, the man didn’t hide in a warm chum (a kind of a tent made of animal skin), but stayed outside, watching the sky or the rolling land, painting a white canvas with various colours. That was Alexander Borisov, a young painter recently graduated from the Academy of Arts. He hadn’t come to the tundra in search of polar bear skin, but looking for a wondrous juxtaposition of tones and colours found in the Arctic scenery.

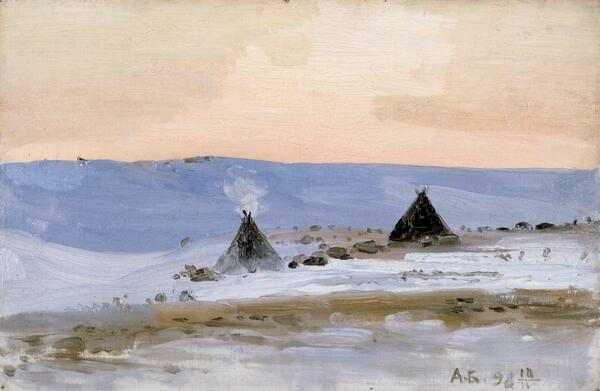

An entry in his diary for April 12th 1898 reads: ‘A day’s rest. A nasty wet weather, a lot of snow. At noon, it was warm and quiet. The wind chilled terribly, although the sky in the North-East was all rainbow and looked to you like a warm summer evening in the South. And only the snow, completely in contrast to the sky, shattered this illusion. … Our shoddy chum stood out dramatically against this pale blue snow. To the right, a line of Bolvanski hillocks stretched, disappearing into the boundless wilderness. This scenery had something implacably stern and infinitely beautiful about it. Staring into it, I wanted to run on and on deeper into the mysterious, wondrous distance. A strange, pleasant feeling filled my soul: affection, and sadness, and humility, and love, and unbending determination and strength — everything was blending together into a single emotion! ’

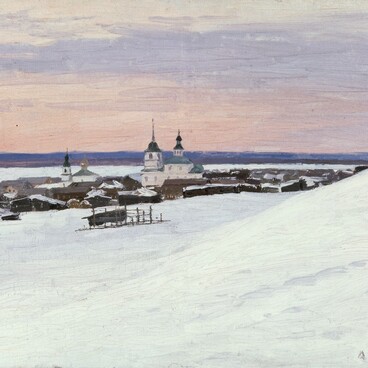

The reindeer caravan is moving slowly across the snow-covered tundra. This picture may seem dull to us, but to the observant eye of the artist it is full of surprising details and wondrous hues. Borisov was fond of the saying coined by Pavel Chistyakov, a prominent Russian portraitist and art teacher: “You must learn to see.” The artist made use of every break on the way, trying to paint as much as he could. However, in spite of his excitement, Borisov didn’t manage to capture this image: he was too busy and exhausted. However, his enthusiasm would manifest itself in many future pictures.

On the 10th of April, he painted April Night in the Bolshezemelskaya Tundra.

An entry in his diary for April 12th 1898 reads: ‘A day’s rest. A nasty wet weather, a lot of snow. At noon, it was warm and quiet. The wind chilled terribly, although the sky in the North-East was all rainbow and looked to you like a warm summer evening in the South. And only the snow, completely in contrast to the sky, shattered this illusion. … Our shoddy chum stood out dramatically against this pale blue snow. To the right, a line of Bolvanski hillocks stretched, disappearing into the boundless wilderness. This scenery had something implacably stern and infinitely beautiful about it. Staring into it, I wanted to run on and on deeper into the mysterious, wondrous distance. A strange, pleasant feeling filled my soul: affection, and sadness, and humility, and love, and unbending determination and strength — everything was blending together into a single emotion! ’

The reindeer caravan is moving slowly across the snow-covered tundra. This picture may seem dull to us, but to the observant eye of the artist it is full of surprising details and wondrous hues. Borisov was fond of the saying coined by Pavel Chistyakov, a prominent Russian portraitist and art teacher: “You must learn to see.” The artist made use of every break on the way, trying to paint as much as he could. However, in spite of his excitement, Borisov didn’t manage to capture this image: he was too busy and exhausted. However, his enthusiasm would manifest itself in many future pictures.

On the 10th of April, he painted April Night in the Bolshezemelskaya Tundra.