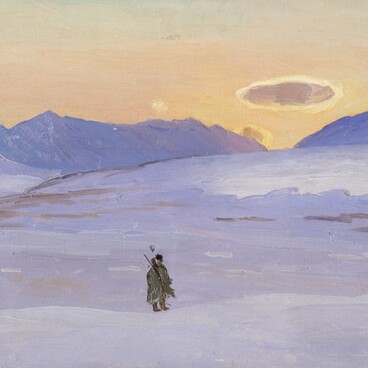

In some way, the words ‘artist’ and ‘traveler’ are similar and even can be considered synonyms in a certain context. To step over a threshold and set off for a journey, the traveler needs to be courageous, while the artist needs to be talented and able to portray everything he sees, hears and feels. And if one person combines both roles, their name will certainly make its mark in history, as was the case with Alexander Borisov. In his Arctic expeditions, he was accompanied by Samoyeds, local residents of the tundra, and so he learned their culture and way of life.

In Borisov’s diary we read, “In all, the Samoyeds are very hospitable people. If someone, even a stranger, happens to come to them, the Samoyed is glad from his heart and offers the most valuable things he possesses to the guest. He gets out butter, which he also likes, and bread, sometimes even cracknels. And if you are in the tundra and there is no wood, he splits his sled to boil the kettle.”

Ustin was Borisov’s guide during his expedition to Novaya Zemlya. This is what Borisov wrote about him: ‘He fed all the dogs, and during hard times, he fed all of us. He was an excellent shot. In his youth, he was a shaman on the Kolguyev Island, beat the drum, but then, he explains, he passed all the demons to his daughter, because “they bother too much, keep asking for a job and make me beat the drum.” During the expedition, he was terribly homesick and imaged the Kolguyev Island as a promised land. In the autumn of 1900, when we got into serious trouble and were drifting on an ice floe in the Kara Sea, Ustin killed seals, and we ate their meat and blood.

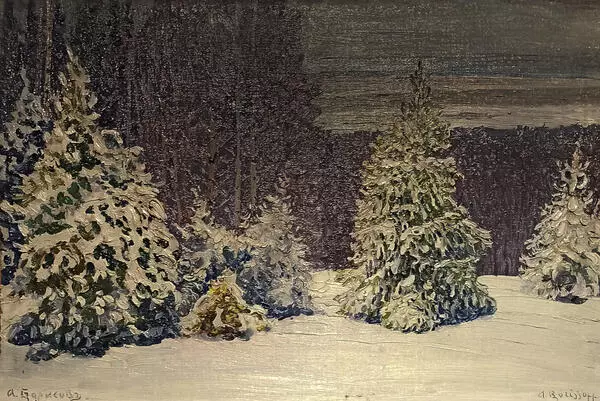

Here’s the situation: there is a snowstorm outside the tent. You can’t go outside. What should you do then? Read? But the two or three books you’ve brought with you are read and reread 20 times over. Talk to your peers? But everything has been talked about already. At moments like this, I used to take the brush and paint something while inside the tent.’

In Borisov’s diary we read, “In all, the Samoyeds are very hospitable people. If someone, even a stranger, happens to come to them, the Samoyed is glad from his heart and offers the most valuable things he possesses to the guest. He gets out butter, which he also likes, and bread, sometimes even cracknels. And if you are in the tundra and there is no wood, he splits his sled to boil the kettle.”

Ustin was Borisov’s guide during his expedition to Novaya Zemlya. This is what Borisov wrote about him: ‘He fed all the dogs, and during hard times, he fed all of us. He was an excellent shot. In his youth, he was a shaman on the Kolguyev Island, beat the drum, but then, he explains, he passed all the demons to his daughter, because “they bother too much, keep asking for a job and make me beat the drum.” During the expedition, he was terribly homesick and imaged the Kolguyev Island as a promised land. In the autumn of 1900, when we got into serious trouble and were drifting on an ice floe in the Kara Sea, Ustin killed seals, and we ate their meat and blood.

Here’s the situation: there is a snowstorm outside the tent. You can’t go outside. What should you do then? Read? But the two or three books you’ve brought with you are read and reread 20 times over. Talk to your peers? But everything has been talked about already. At moments like this, I used to take the brush and paint something while inside the tent.’