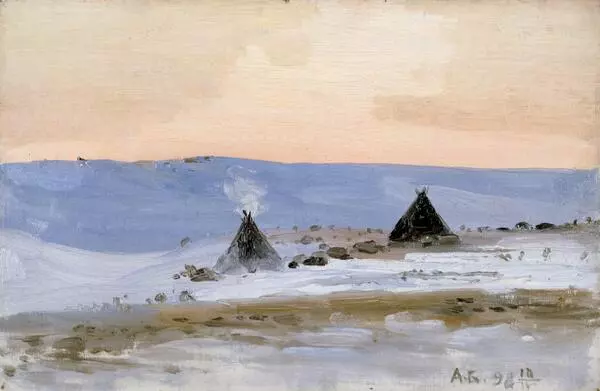

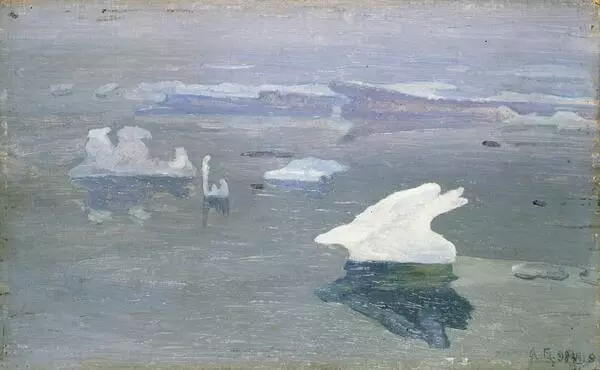

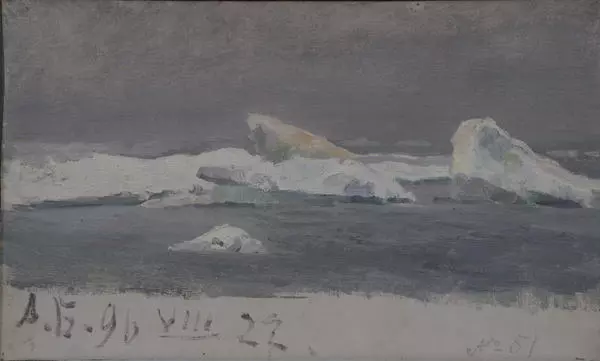

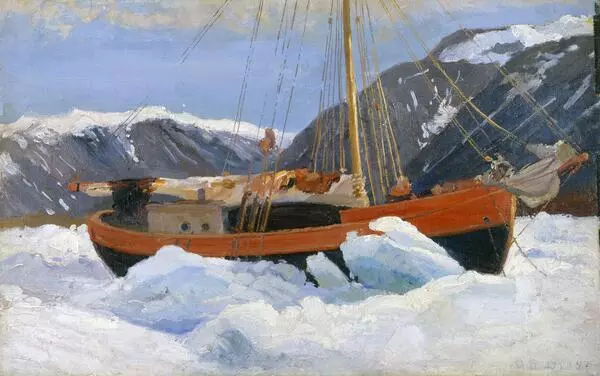

What was so attractive about artistic expeditions to the Arctic, long and dangerous as they were? First of all, the artists that undertook such expeditions were looking for inspiration, for new experiences, new motifs and colours. During the journey, they didn’t have to do repetitive chores, but had a lot of time to watch, observe, reflect and create. Alexander Borisov used to refer to his expeditions as “artistic and exploratory excursions''. When he came back from his journey across Bolshezemelskaya Tundra, his fellow painters were astonished by the original motifs, composition and tonality of the paintings Borisov presented. Among them was the study Chekin Bay in Novaya Zemlya.

Nicholas Roerich, a celebrated Russian painter and philosopher, once observed: “Sometimes, while hunting on an unbearably hot day, you get envious when you hear your fellow cry: I have found a creek! The water is clear! I think that, for many painters, Borisov”s work is similar to this call. He managed to find a new creek, not trodden by anyone, without any old paint tubes on the bottom.”

On one hand, an open-air study is just an exercise, a sketch, sometimes lacking any artistic value. On the other hand, it is the very soul of the artist, his feeling and emotions, his view of the fleeting moment, the mood he has captured.

In his expeditions, Borisov painted more than 250 studies and complete pictures, most of which were painted outside, in cold and wind. This is what Borisov wrote: “It was very hard to work. I had to cut the bristles of the brush, making them short. It was almost impossible to grind colours. The cold makes the paint into a dense paste that doesn”t stick to the brush and doesn”t spread on the canvas. Sometimes, during my “polar” painting sessions, even turpentine — the only thing that helped me to thin the paint — didn’t work, because it was crystallizing in the freezing cold. Some of my studies were painted at 28 °C below zero, three or four were painted at 37 °C below zero. I had to squeeze the brush in my fist, covered with the sleeve of my malitsa coat, and press it into the canvas to apply the paint. The brush was cracking, the hands were going numb and useless. But I kept painting, anxious to capture those whimsical, uniquely beautiful images of our North.’

Nicholas Roerich, a celebrated Russian painter and philosopher, once observed: “Sometimes, while hunting on an unbearably hot day, you get envious when you hear your fellow cry: I have found a creek! The water is clear! I think that, for many painters, Borisov”s work is similar to this call. He managed to find a new creek, not trodden by anyone, without any old paint tubes on the bottom.”

On one hand, an open-air study is just an exercise, a sketch, sometimes lacking any artistic value. On the other hand, it is the very soul of the artist, his feeling and emotions, his view of the fleeting moment, the mood he has captured.

In his expeditions, Borisov painted more than 250 studies and complete pictures, most of which were painted outside, in cold and wind. This is what Borisov wrote: “It was very hard to work. I had to cut the bristles of the brush, making them short. It was almost impossible to grind colours. The cold makes the paint into a dense paste that doesn”t stick to the brush and doesn”t spread on the canvas. Sometimes, during my “polar” painting sessions, even turpentine — the only thing that helped me to thin the paint — didn’t work, because it was crystallizing in the freezing cold. Some of my studies were painted at 28 °C below zero, three or four were painted at 37 °C below zero. I had to squeeze the brush in my fist, covered with the sleeve of my malitsa coat, and press it into the canvas to apply the paint. The brush was cracking, the hands were going numb and useless. But I kept painting, anxious to capture those whimsical, uniquely beautiful images of our North.’