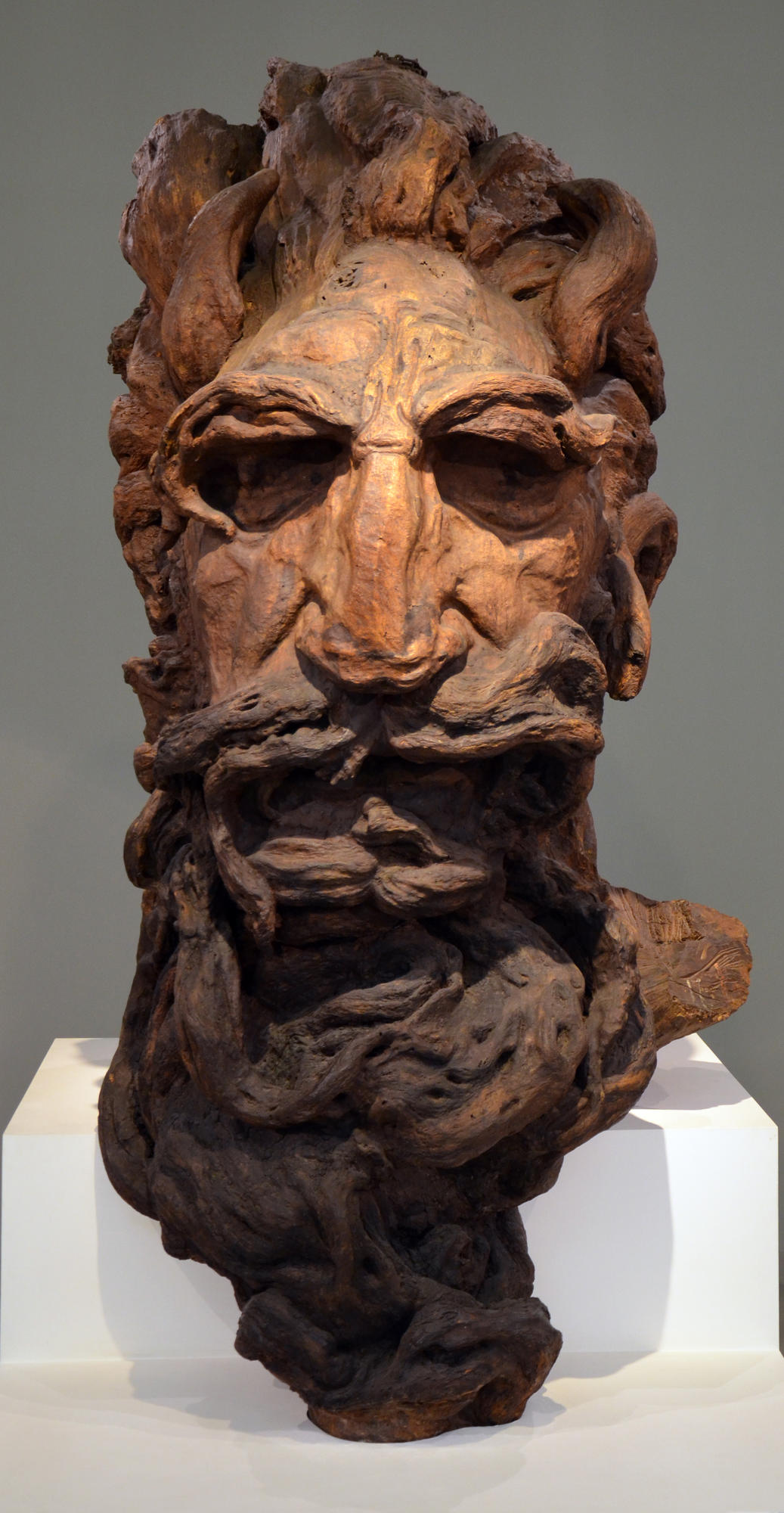

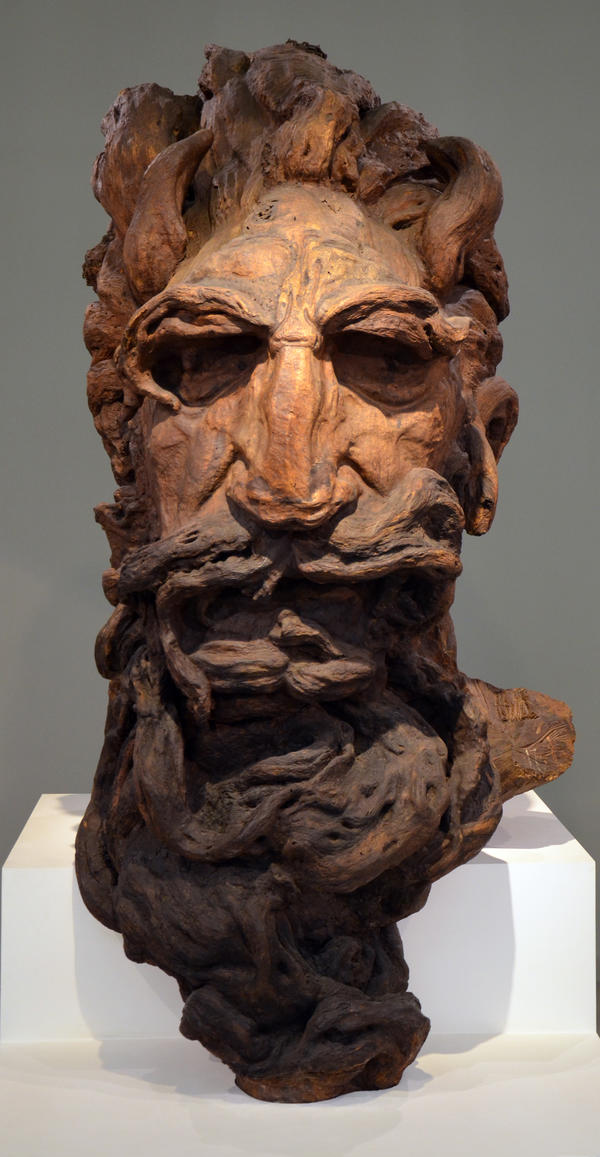

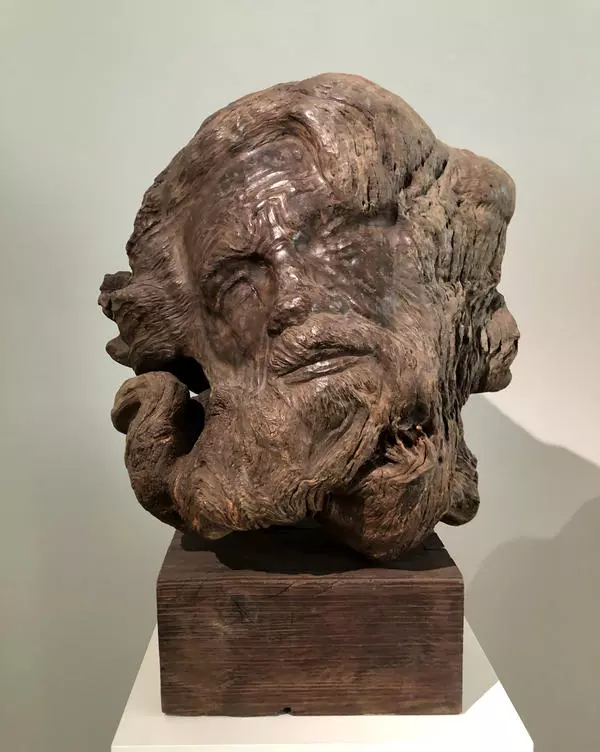

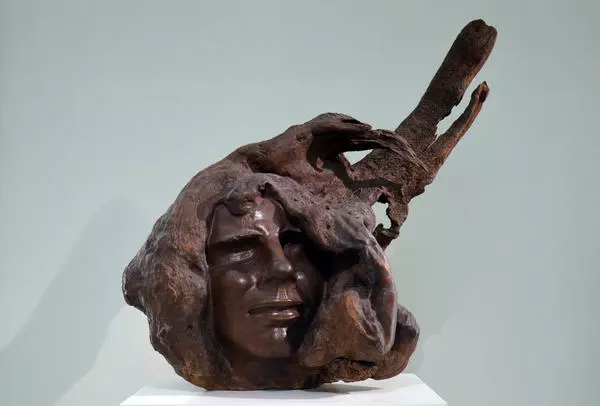

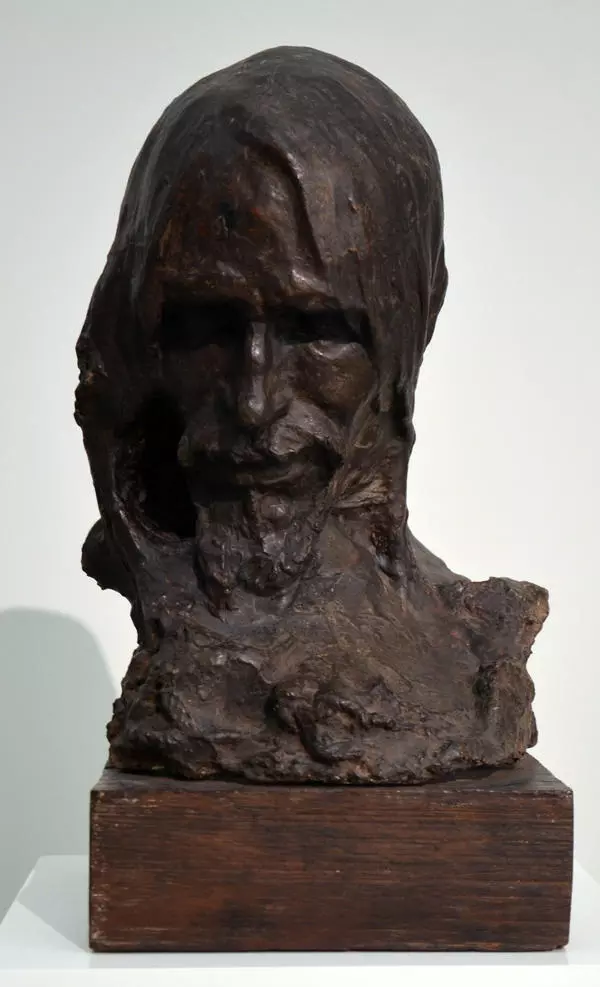

In August 1932, while working in Argentina, S.D. Erzia created Moses, one of his most grandiose works. The gigantic head of the biblical prophet is made of a single piece of the South American algarrobo wood, capricious, unpredictable and very durable material, as if reluctant to surrender to sculptor’s hands. For Stepan Erzia, it became true love.

It was not for nothing that the Argentinean mass-media called the sculptor the “conqueror of quebracho”: out of 3,100 disparate pieces fastened together with self-made glue, the author managed to assemble an image of an unusual emotional glow, full of powerful, amazing energy. An important role in this was played by the method of organically incorporating natural fragments into the composition: the wavy strands of the prophet’s long beard are formed by bizarre interweaving of the tree roots.

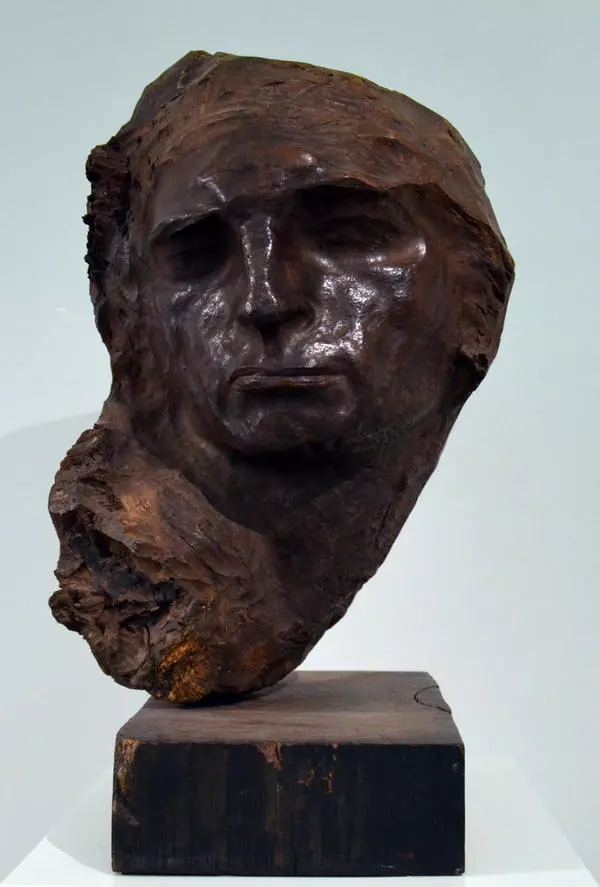

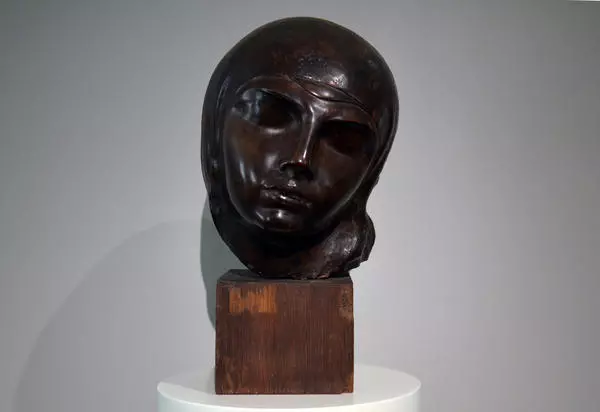

Many art historians and connoisseurs have tried to comprehend the deep essence of Moses. Many thousands of spectators stand in awe before its greatness. The stubborn face ploughed with wrinkles, the swollen veins of the forehead, the frowning eyebrows and thunder-like eyes, this is how Moses is revealed to us, and it is no longer possible to picture him in any other way.

The impression of liveliness and variability is enhanced by the fact that the pupils of the eyes are only barely outlined by the sculptor. Therefore, the observer, while changing the view point, always sees not only the direction of his gaze, but also the expression of the eyes. The fact that the perception depends on the angle adds even more expression. Moses appears as a formidable leader, then a sage man immersed in difficult thoughts, then an angry exposer of vices, or a fairy-tale hero.

The author achieved a sensation of powerful strength and conveyed the tension emanating from the prophet’s appearance. He shows Moses as an unconditional leader capable of inflaming his adherers with some idea, and to lead people, subordinating an entire nation to his will. In Moses’ austere and spiritual features, a life lived in a steady pursuit of the cherished goal is imprinted.

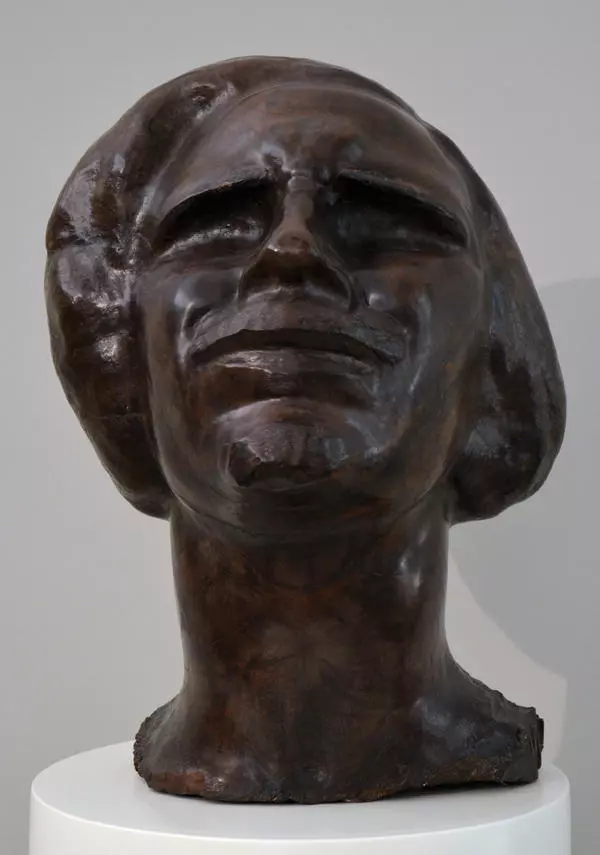

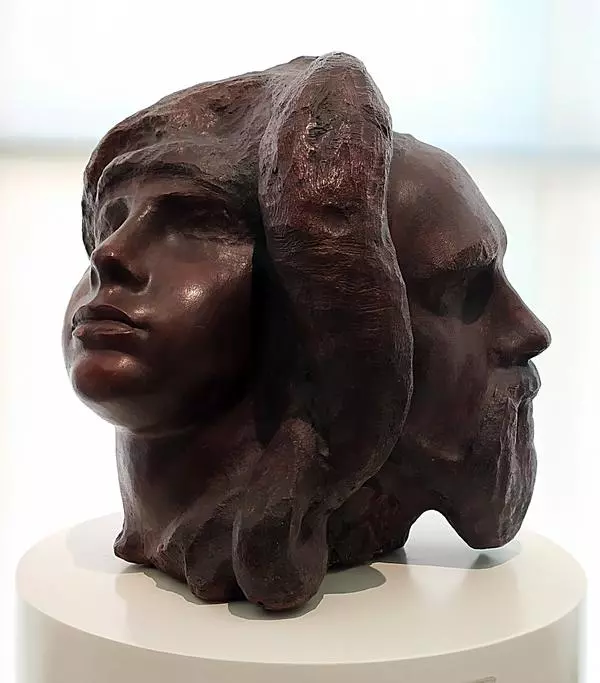

For thousands of years, artists around the world have found inspiration in mythology — pagan, antique, and Christian. In the legends generated by people’s fantasy, real historical events are intertwined with fiction; they transmit ideas about the creation of the world, natural phenomena, moral and ethical standards.

The rich content of myths provided tremendous freedom of interpretation and thereby helped to translate the ideals and problems of each era into art. In his creation, the sculptor expressed his own, rather than mystical, ideas, his own earthly thoughts and feelings, and filled the abstract concepts with tangible life meaning.

Today it is impossible to say with certainty how Stepan Erzia began to take an interest in mythological themes. It is difficult to fully appreciate the works belonging to this series, since some of them are known only from archival photographs. The fabulous images captured with genuine innovation tend to outgrow their original framework, gaining depth and ambiguity.

An American millionaire offered Erzia fabulous money for Moses. “I am a lonely person, I have no children. Sculptures are my children. Who would be selling their children?” the proud artist answered.

It was not for nothing that the Argentinean mass-media called the sculptor the “conqueror of quebracho”: out of 3,100 disparate pieces fastened together with self-made glue, the author managed to assemble an image of an unusual emotional glow, full of powerful, amazing energy. An important role in this was played by the method of organically incorporating natural fragments into the composition: the wavy strands of the prophet’s long beard are formed by bizarre interweaving of the tree roots.

Many art historians and connoisseurs have tried to comprehend the deep essence of Moses. Many thousands of spectators stand in awe before its greatness. The stubborn face ploughed with wrinkles, the swollen veins of the forehead, the frowning eyebrows and thunder-like eyes, this is how Moses is revealed to us, and it is no longer possible to picture him in any other way.

The impression of liveliness and variability is enhanced by the fact that the pupils of the eyes are only barely outlined by the sculptor. Therefore, the observer, while changing the view point, always sees not only the direction of his gaze, but also the expression of the eyes. The fact that the perception depends on the angle adds even more expression. Moses appears as a formidable leader, then a sage man immersed in difficult thoughts, then an angry exposer of vices, or a fairy-tale hero.

The author achieved a sensation of powerful strength and conveyed the tension emanating from the prophet’s appearance. He shows Moses as an unconditional leader capable of inflaming his adherers with some idea, and to lead people, subordinating an entire nation to his will. In Moses’ austere and spiritual features, a life lived in a steady pursuit of the cherished goal is imprinted.

For thousands of years, artists around the world have found inspiration in mythology — pagan, antique, and Christian. In the legends generated by people’s fantasy, real historical events are intertwined with fiction; they transmit ideas about the creation of the world, natural phenomena, moral and ethical standards.

The rich content of myths provided tremendous freedom of interpretation and thereby helped to translate the ideals and problems of each era into art. In his creation, the sculptor expressed his own, rather than mystical, ideas, his own earthly thoughts and feelings, and filled the abstract concepts with tangible life meaning.

Today it is impossible to say with certainty how Stepan Erzia began to take an interest in mythological themes. It is difficult to fully appreciate the works belonging to this series, since some of them are known only from archival photographs. The fabulous images captured with genuine innovation tend to outgrow their original framework, gaining depth and ambiguity.

An American millionaire offered Erzia fabulous money for Moses. “I am a lonely person, I have no children. Sculptures are my children. Who would be selling their children?” the proud artist answered.