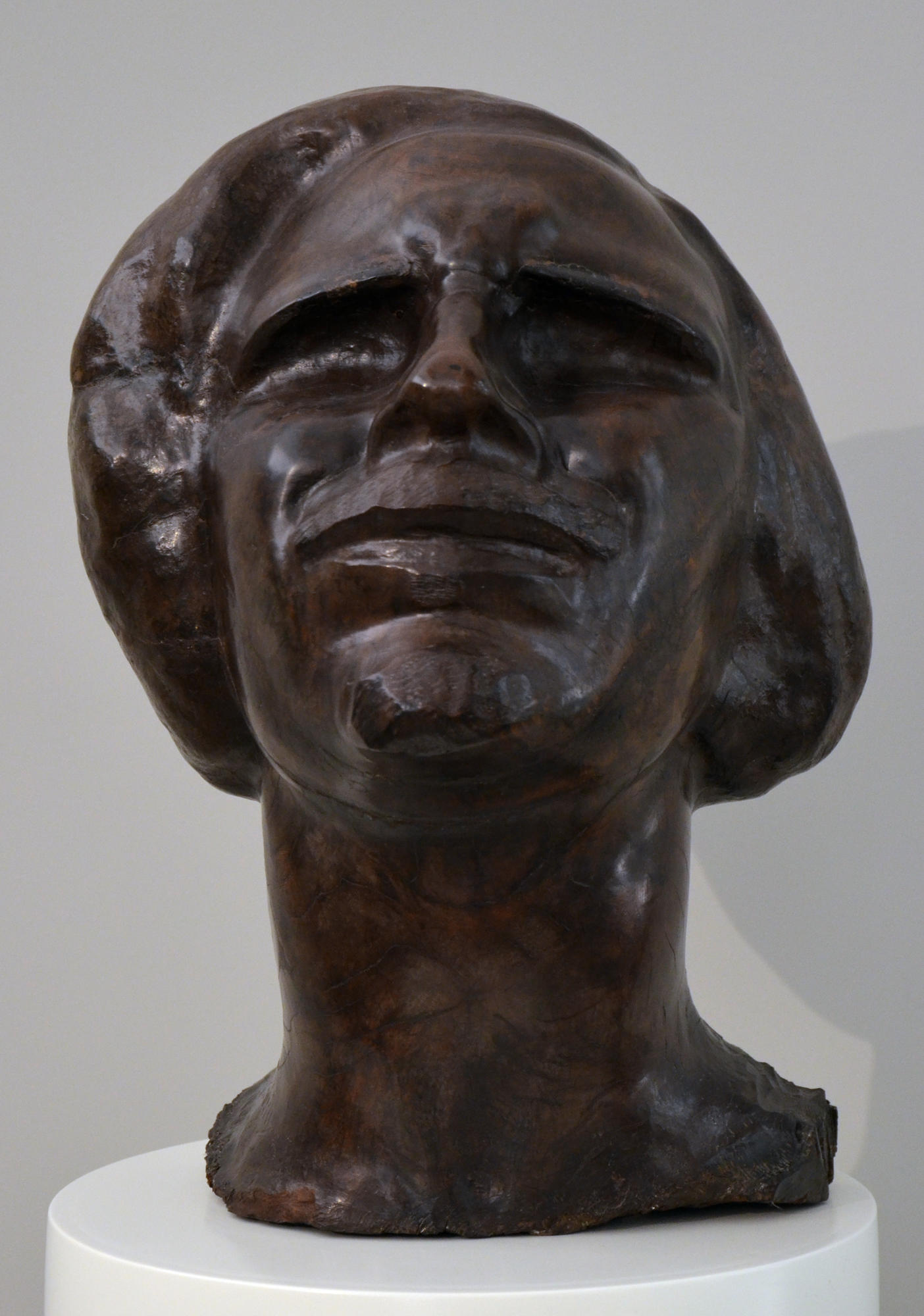

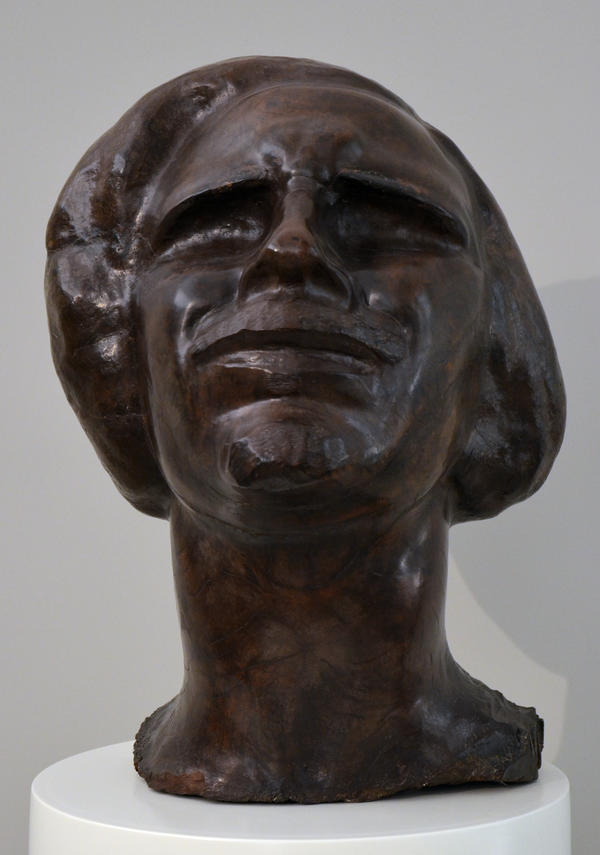

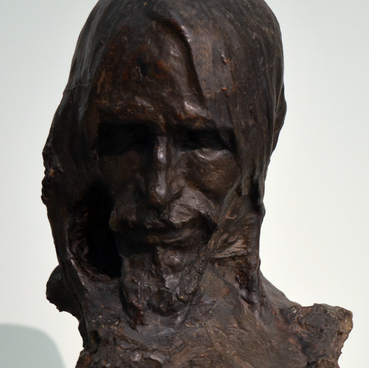

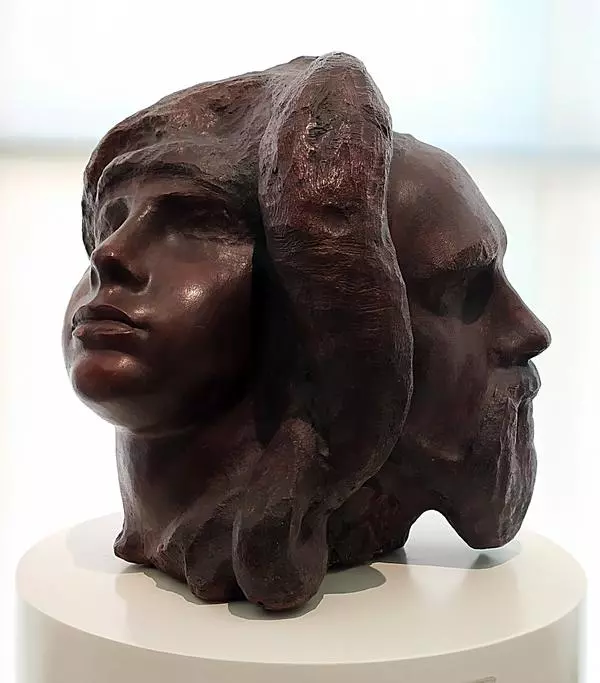

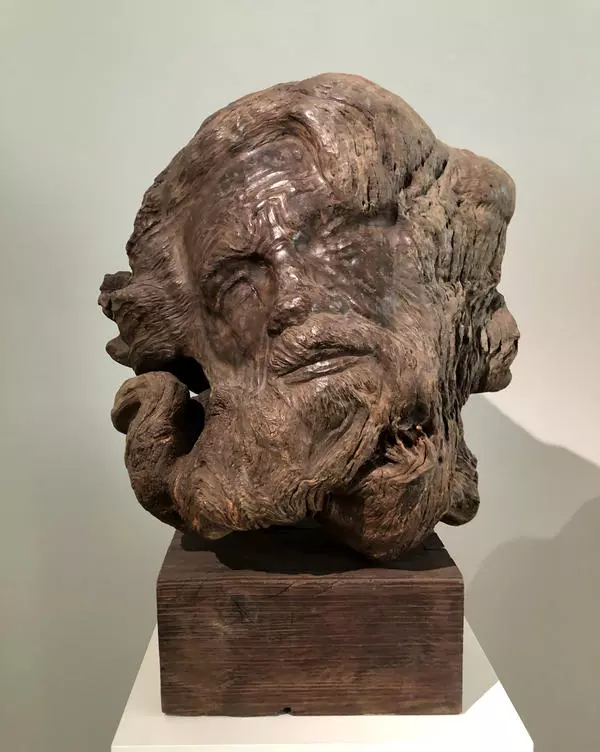

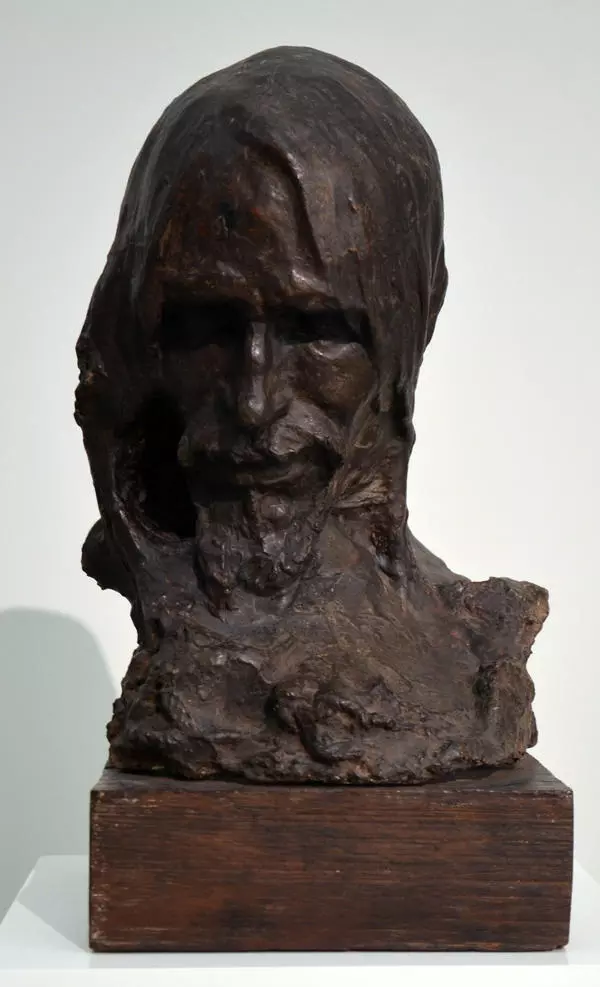

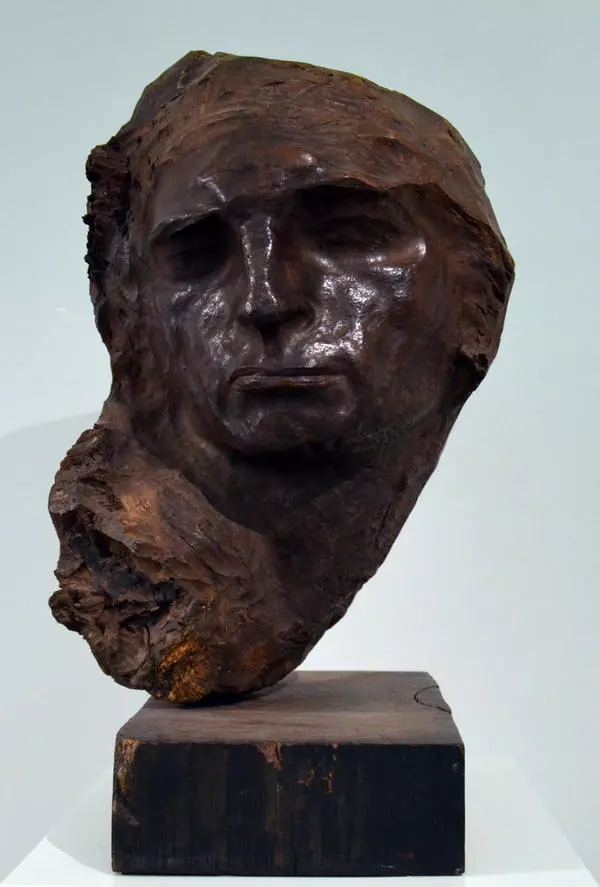

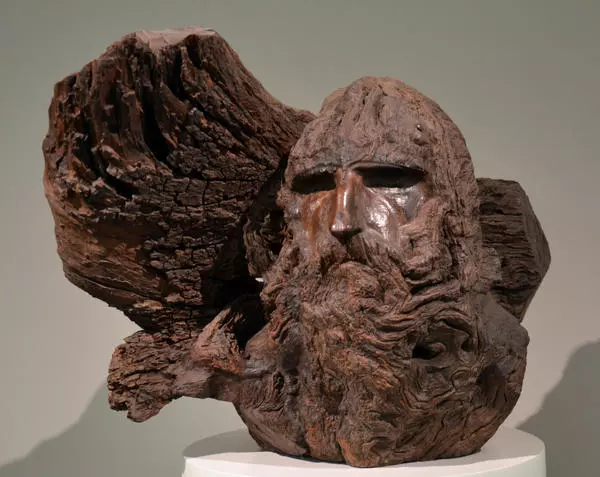

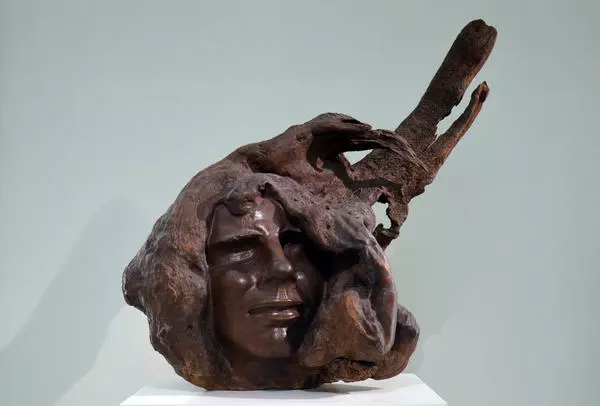

This emotional portrait – a portrait of confession, summing up results, and nostalgia, - is a true masterpiece by Stepan Erzia. The sculptor created it at the age of seventy in Argentina, three years before he returned to Russia.

While rendering his own individual traits and depicting himself a man in his prime - with a high forehead, deep-set eyes, and brows dolefully knit together, - the artist still put an emphasis on the emotional intensity of the image. One can read a complex range of feelings in the turned up face: the heart rending notes of painful craving, suffering and desperation. Still, there is impassioned hope shining through all that.

The realistic principle combined with thoughtful penetration into the man’s inner world adds particular loftiness and spirituality to the image. The self-portrait demonstrates the sculptor’s ability to disclose the nuances of human feelings by animating a mass of wood.

The sculpture was made of quebracho, which is the name of the bark and wood of several varieties of trees that grow in South America. Its color varies from light yellow to dark brown, red or almost black. Stepan Erzia most frequently worked with the algaroba wood. Quebracho is unusually dense and hard, and it requires much skill and experience from the sculptor.

Quebracho became the artist’s favorite material for many years, and he spent twenty-three years in Argentina for the sake of it. Over that period, Stepan Erzia made more than three hundred sculptures and developed his own artistic technique that combined plasticity and expressiveness of shape. The sculptor was skilled in bringing together smooth surfaces as if cast in glass and the natural texture of wood. Gnarled algabora wood stirred the imagination of the artist and prompted the sophisticated shapes of the statues.

Stepan Erzia regarded wood carving as a continuation of Mordovian folk traditions, where the forest and the wood were the sources of inspiration and a material for building and decorating homes, handcrafting and making household items. Every peasant in Mordovia, Stepan Erzia being no exception, had the skills of a woodworker and a carpenter. Even when he lived in the Caucasus, the sculptor made attempts at wood sculpting, and created a few works of wood: Leda and the Swan, The Portrait of a Woman, The Whisper.

Life in Argentina, full of artistic explorations, was not easy. The artist was longing for his motherland. The quebracho self-portrait is rather the portrait of his soul: the old sculptor portrayed himself as a suffering young man with his head thrown back looking upwards - into the still bright future. Or maybe into the Eternity.

While rendering his own individual traits and depicting himself a man in his prime - with a high forehead, deep-set eyes, and brows dolefully knit together, - the artist still put an emphasis on the emotional intensity of the image. One can read a complex range of feelings in the turned up face: the heart rending notes of painful craving, suffering and desperation. Still, there is impassioned hope shining through all that.

The realistic principle combined with thoughtful penetration into the man’s inner world adds particular loftiness and spirituality to the image. The self-portrait demonstrates the sculptor’s ability to disclose the nuances of human feelings by animating a mass of wood.

The sculpture was made of quebracho, which is the name of the bark and wood of several varieties of trees that grow in South America. Its color varies from light yellow to dark brown, red or almost black. Stepan Erzia most frequently worked with the algaroba wood. Quebracho is unusually dense and hard, and it requires much skill and experience from the sculptor.

Quebracho became the artist’s favorite material for many years, and he spent twenty-three years in Argentina for the sake of it. Over that period, Stepan Erzia made more than three hundred sculptures and developed his own artistic technique that combined plasticity and expressiveness of shape. The sculptor was skilled in bringing together smooth surfaces as if cast in glass and the natural texture of wood. Gnarled algabora wood stirred the imagination of the artist and prompted the sophisticated shapes of the statues.

Stepan Erzia regarded wood carving as a continuation of Mordovian folk traditions, where the forest and the wood were the sources of inspiration and a material for building and decorating homes, handcrafting and making household items. Every peasant in Mordovia, Stepan Erzia being no exception, had the skills of a woodworker and a carpenter. Even when he lived in the Caucasus, the sculptor made attempts at wood sculpting, and created a few works of wood: Leda and the Swan, The Portrait of a Woman, The Whisper.

Life in Argentina, full of artistic explorations, was not easy. The artist was longing for his motherland. The quebracho self-portrait is rather the portrait of his soul: the old sculptor portrayed himself as a suffering young man with his head thrown back looking upwards - into the still bright future. Or maybe into the Eternity.