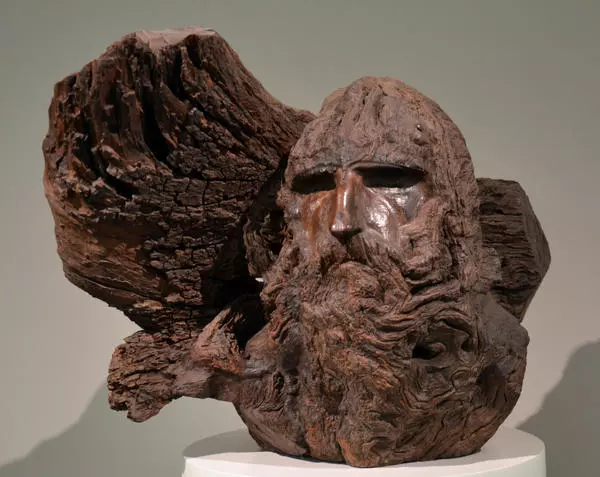

Stepan Dmitrievich Erzia (Nefedov) (1876-1959) was a painter and sculptor who descended from a Mari ethnic group of Erzia. He chose the name of his native ethnic group for his artistic pseudonym and made it world-famous. Over his artistic life, the master worked in Russia, specifically, in Moscow, Yekaterinburg, Batumi, Baku, and Novorossiysk, as well as Europe, in Italy and France. He spent three years in Argentina, where he discovered a unique material for his artwork: locally grown quebracho and algarrobo wood. He took such a fancy to that material as to stay in South America for a long time. In Mordovia, Stepan Dmitrievich Erzia is an enduring brand and the museum named after him is the symbol of the Republic.

Stepan Erzia was born to a family of Mordovian peasants in the village of Bayevo, Alatyr District, Simbirsk Province. He graduated from the Moscow School of Painting and Sculpture where he studied under sculptors Sergey Volnukhin and Pavel Trubetskoy. After graduation, he went on a creative travel of Europe and successfully participated in international exhibitions in Venice, Milano, and Paris, which brought him international fame. He was dubbed ‘Russian Rodin’ who combined folk culture with a revolutionary vision of artistic images and unusual plastic art.

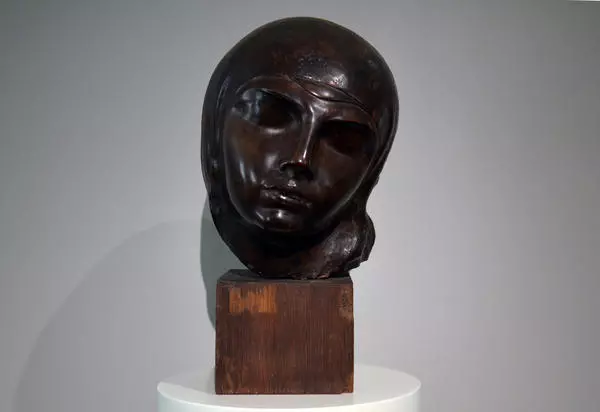

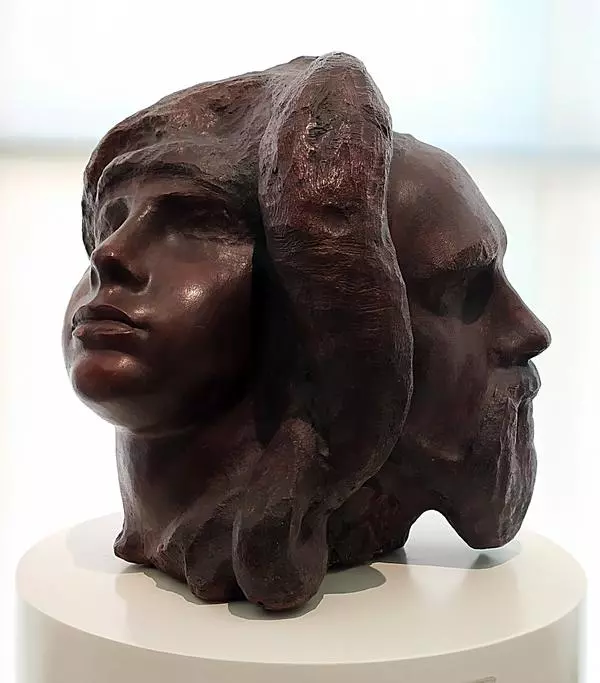

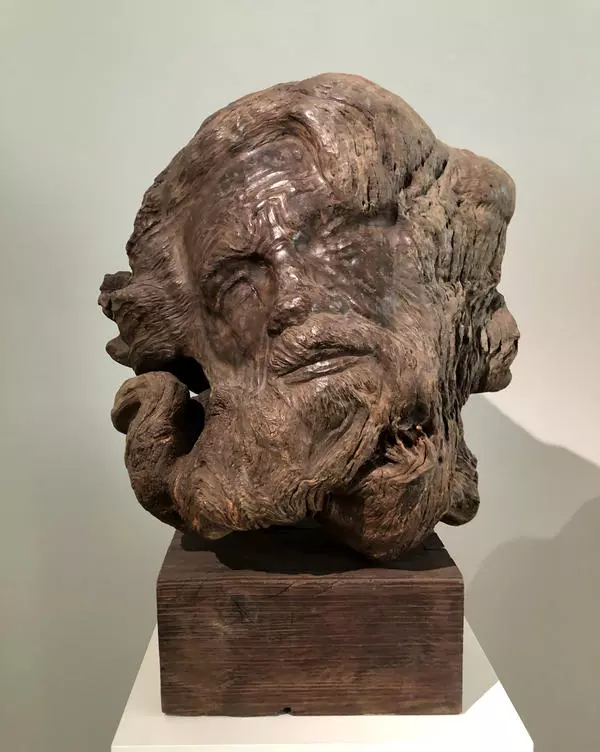

Stepan Erzia’s Self-Portrait was painted in the master’s early artistic period, the Italian period. Abroad, he studied the art of sculpture and mastered materials new to him, attempted to do without preliminary sketches cutting artful shapes from stone in one go. For that sculpture’s material the master experimented with tinted cement widely used at the time.

His life in Italy was full of hardships and travails in quest for his creative ideal. In the Self-Portrait, the master depicted himself as a tired man with a scrawny face and sorrowfully wrinkled brows, lost in sad thought.

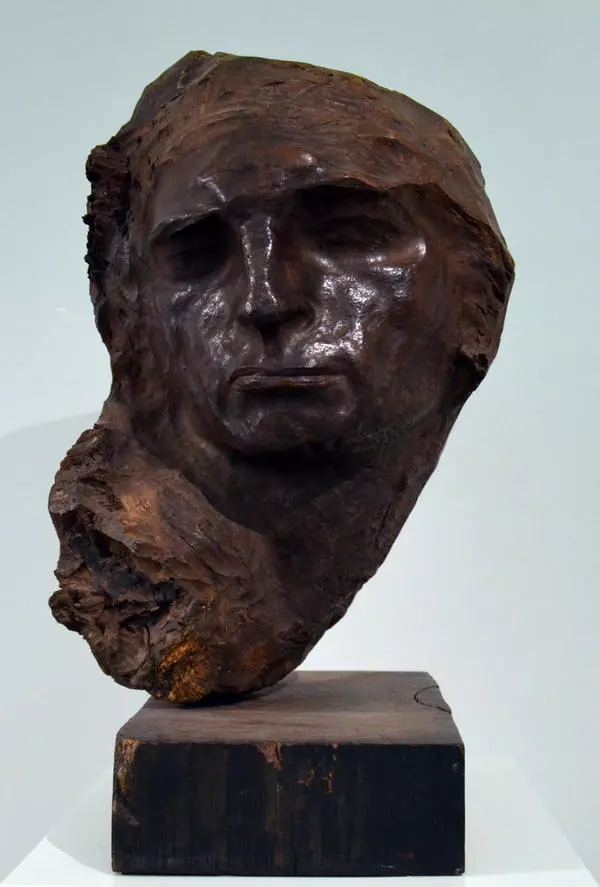

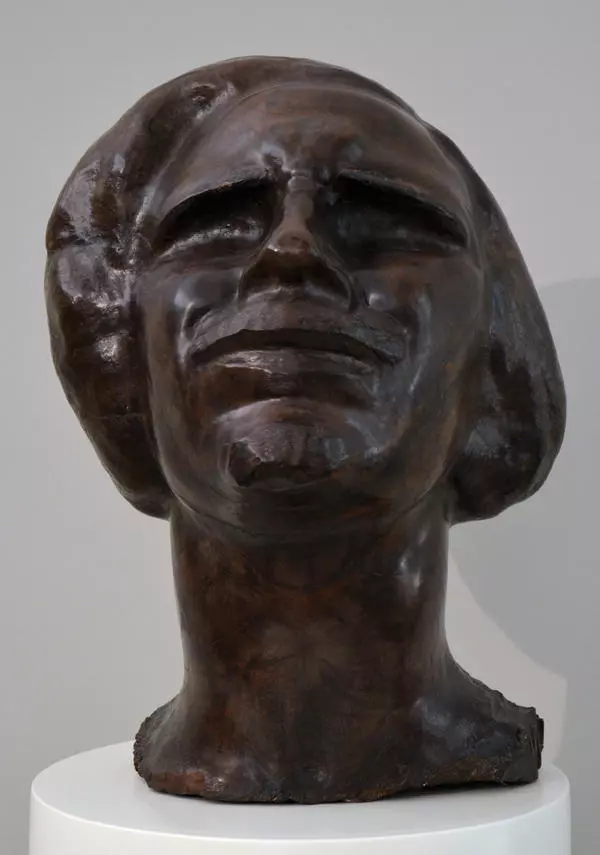

The inscription on the backside of one of the sculpture’s photos in the author’s handwriting says Cristo (Christ). The mournful image of the figure indeed puts to mind Jesus Christ. The spirit world was close to Stepan Erzia’s heart since childhood: he attended a parochial school in the village of Altyshevo (presently, the Alatyr District, Chuvash Republic), and studied painting in icon painting workshops in Alatyr and later Kazan. Stepan Erzia knew the iconography of the Savior very well and was fascinated with it all his life. The master repeatedly returned to its interpretation in his artwork.

Stepan Erzia was born to a family of Mordovian peasants in the village of Bayevo, Alatyr District, Simbirsk Province. He graduated from the Moscow School of Painting and Sculpture where he studied under sculptors Sergey Volnukhin and Pavel Trubetskoy. After graduation, he went on a creative travel of Europe and successfully participated in international exhibitions in Venice, Milano, and Paris, which brought him international fame. He was dubbed ‘Russian Rodin’ who combined folk culture with a revolutionary vision of artistic images and unusual plastic art.

Stepan Erzia’s Self-Portrait was painted in the master’s early artistic period, the Italian period. Abroad, he studied the art of sculpture and mastered materials new to him, attempted to do without preliminary sketches cutting artful shapes from stone in one go. For that sculpture’s material the master experimented with tinted cement widely used at the time.

His life in Italy was full of hardships and travails in quest for his creative ideal. In the Self-Portrait, the master depicted himself as a tired man with a scrawny face and sorrowfully wrinkled brows, lost in sad thought.

The inscription on the backside of one of the sculpture’s photos in the author’s handwriting says Cristo (Christ). The mournful image of the figure indeed puts to mind Jesus Christ. The spirit world was close to Stepan Erzia’s heart since childhood: he attended a parochial school in the village of Altyshevo (presently, the Alatyr District, Chuvash Republic), and studied painting in icon painting workshops in Alatyr and later Kazan. Stepan Erzia knew the iconography of the Savior very well and was fascinated with it all his life. The master repeatedly returned to its interpretation in his artwork.