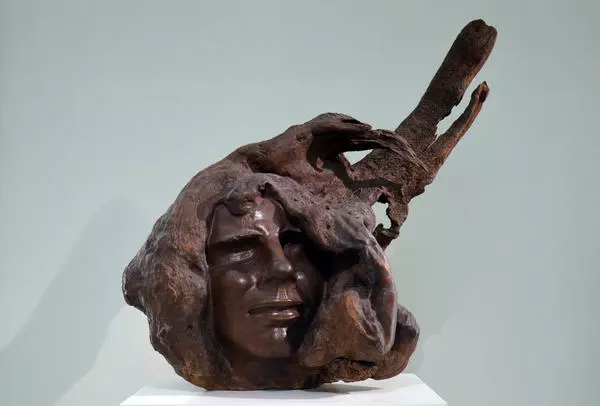

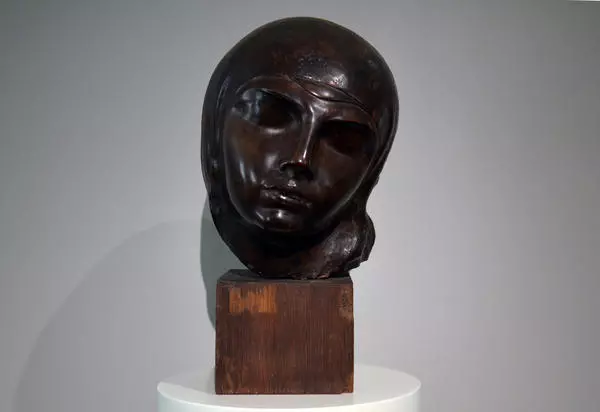

Shaken Akhmetzhanova’s sculptural portrait Kazakh woman, made by Stepan Erzia, was to become a part of a large series of works that unfortunately was not fulfilled by the master. Looking at the beautiful and inspired face of a woman worker carved from wood, it is easy to comprehend the author’s idea to create images of people of the new Russia.

It’s not just the similarity of appearance with the prototype - a simple milkmaid, awarded the title of Hero of Socialist Labor. Erzia revealed and conveyed to the viewer the main thing - the character of the woman. Calm and wise, she looks at the viewer with self-esteem, but not pride. An open look, a light smile demonstrate confidence in a bright future, joy of belonging to a common big cause.

The master created the portrait of the Kazakh woman after his coming back to the Soviet Union, where he returned after many years abroad. In Buenos Aires, where the sculptor spent more than twenty years, he discovered special breeds of wood: Urundai, Quebracho and Algarrobo, which have a peculiar texture, amazing hardness and density, beautiful shades. The locals used those breeds of wood to make sleepers, and Stepan Erzia honed his own skills on it.

His whole life was devoted to art. Wherever the master lived, his soul was desperate to get back to the Motherland. Remaining a citizen of the Soviet Union, he did not accept Argentine citizenship. Hoping to return to Russia one day, the sculptor carefully kept the long-expired Soviet passport.

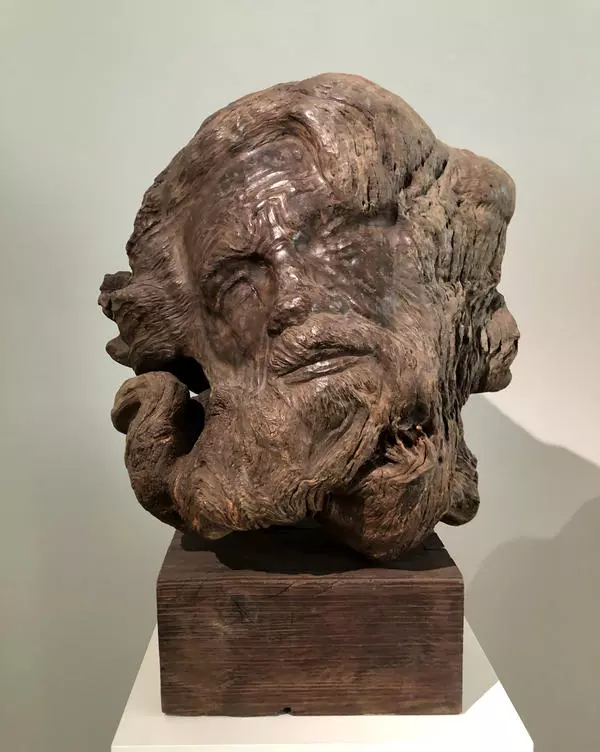

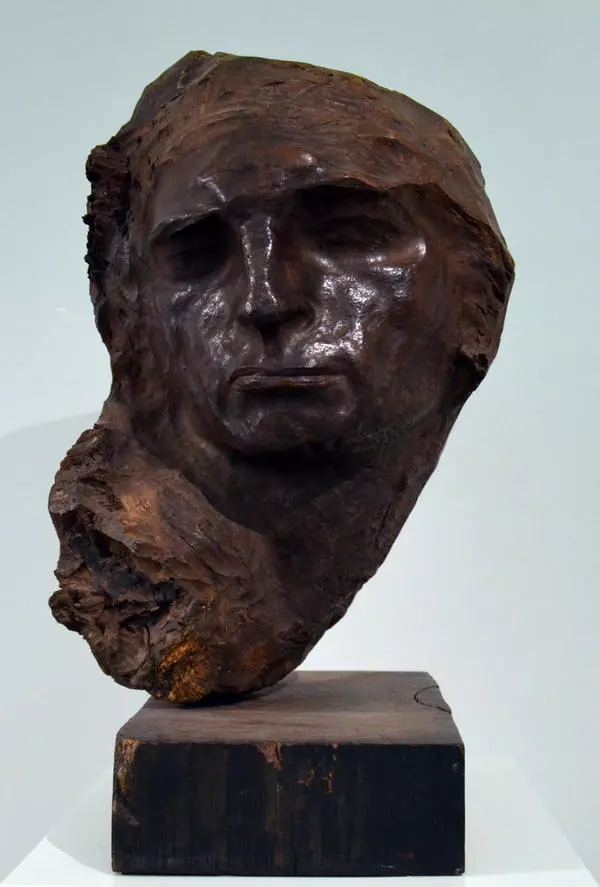

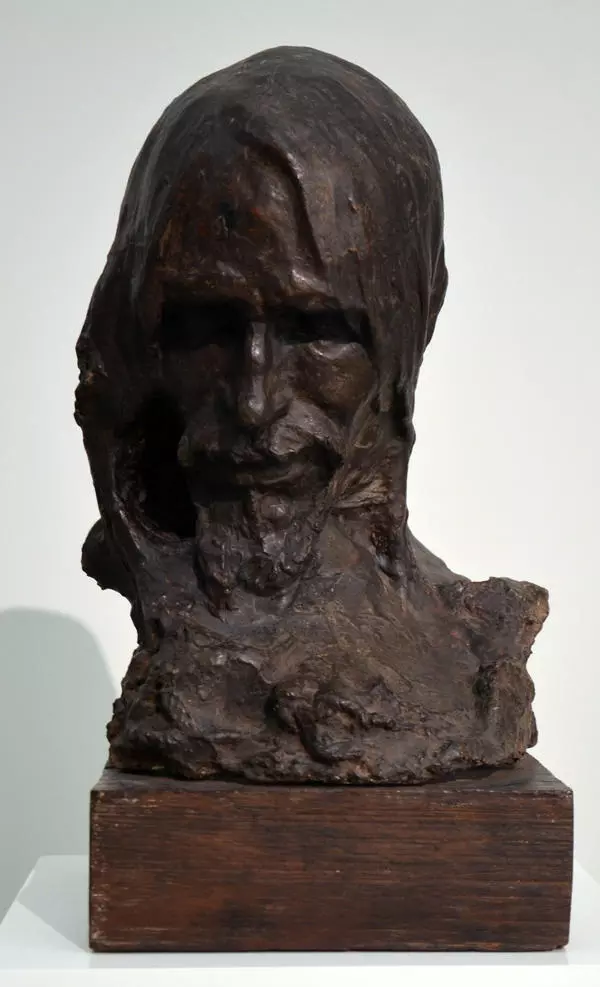

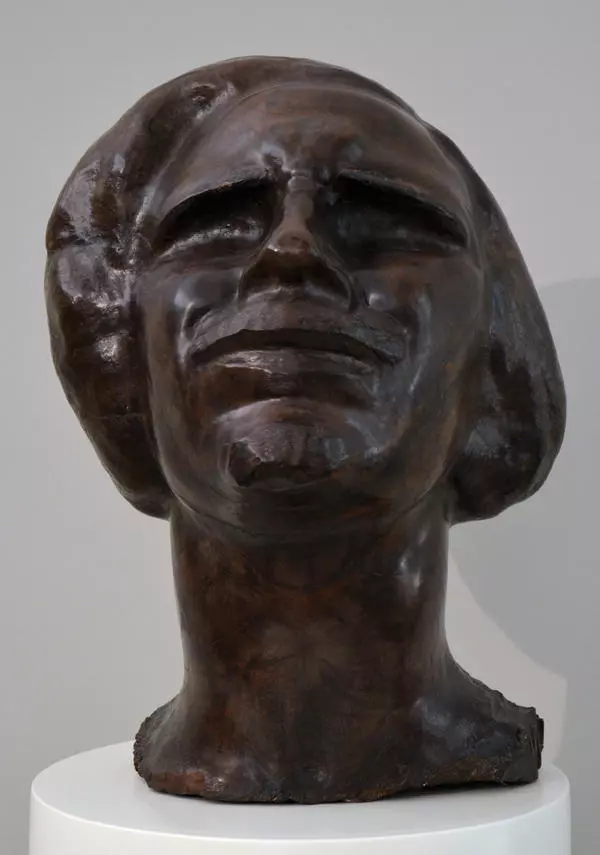

Many works created in the foreign land are imbued with a sense of despair and hopelessness, tragedy and internal contradictions. But it was the long-term Argentine period that became the most significant in Erzia’s work: the artist found his own theme, developed his own unique style.

The artist returned to his homeland in 1951. He brought with him a collection of sculptural works and the favorite exotic natural material. The solo exhibition, held in 1954 in the exhibition hall on the Kuznetsky Bridge, aroused the most acute interest among the audience and critics. Erzia feared that the Soviet public would not accept his authentic art. But the anxiety was in vain: the sculptor got triumphal reception.

Kazakh woman is made of the Algarrobo wood in a new manner of the master. Previously he had created ‘in co-authorship with nature, ’ subjecting only a small piece of wood to processing. Carefully showing the face and occasionally hands, the sculptor organically ‘weaved’ the remaining natural part into the hairstyles of the characters, hats, details of fluttering clothes.

Akhmetzhanova’s portrait was fully worked out, from pupils to hair. Having studied and subjugated the wood, the master gave up his usual expressive external effects. They were replaced by a smooth flow of wood fibers. The use of this technique gave the image of the young milkmaid more freedom and internal deliverance. This is one of the first portraits where the character is smiling, though the smile is restrained.

Surprisingly, Stepan Erzia was one of the few masters who created his works from memory, without preliminary sketches. Even his early sculptures were created by the method of direct carving in stone. Being a fine psychologist with superb visual memory and having excellent skills of processing of the material, the sculptor masterfully conveyed the deepest shades of human feelings without any drafts. The image of the woman, full of life and peace of mind, eloquently confirms this.

It’s not just the similarity of appearance with the prototype - a simple milkmaid, awarded the title of Hero of Socialist Labor. Erzia revealed and conveyed to the viewer the main thing - the character of the woman. Calm and wise, she looks at the viewer with self-esteem, but not pride. An open look, a light smile demonstrate confidence in a bright future, joy of belonging to a common big cause.

The master created the portrait of the Kazakh woman after his coming back to the Soviet Union, where he returned after many years abroad. In Buenos Aires, where the sculptor spent more than twenty years, he discovered special breeds of wood: Urundai, Quebracho and Algarrobo, which have a peculiar texture, amazing hardness and density, beautiful shades. The locals used those breeds of wood to make sleepers, and Stepan Erzia honed his own skills on it.

His whole life was devoted to art. Wherever the master lived, his soul was desperate to get back to the Motherland. Remaining a citizen of the Soviet Union, he did not accept Argentine citizenship. Hoping to return to Russia one day, the sculptor carefully kept the long-expired Soviet passport.

Many works created in the foreign land are imbued with a sense of despair and hopelessness, tragedy and internal contradictions. But it was the long-term Argentine period that became the most significant in Erzia’s work: the artist found his own theme, developed his own unique style.

The artist returned to his homeland in 1951. He brought with him a collection of sculptural works and the favorite exotic natural material. The solo exhibition, held in 1954 in the exhibition hall on the Kuznetsky Bridge, aroused the most acute interest among the audience and critics. Erzia feared that the Soviet public would not accept his authentic art. But the anxiety was in vain: the sculptor got triumphal reception.

Kazakh woman is made of the Algarrobo wood in a new manner of the master. Previously he had created ‘in co-authorship with nature, ’ subjecting only a small piece of wood to processing. Carefully showing the face and occasionally hands, the sculptor organically ‘weaved’ the remaining natural part into the hairstyles of the characters, hats, details of fluttering clothes.

Akhmetzhanova’s portrait was fully worked out, from pupils to hair. Having studied and subjugated the wood, the master gave up his usual expressive external effects. They were replaced by a smooth flow of wood fibers. The use of this technique gave the image of the young milkmaid more freedom and internal deliverance. This is one of the first portraits where the character is smiling, though the smile is restrained.

Surprisingly, Stepan Erzia was one of the few masters who created his works from memory, without preliminary sketches. Even his early sculptures were created by the method of direct carving in stone. Being a fine psychologist with superb visual memory and having excellent skills of processing of the material, the sculptor masterfully conveyed the deepest shades of human feelings without any drafts. The image of the woman, full of life and peace of mind, eloquently confirms this.