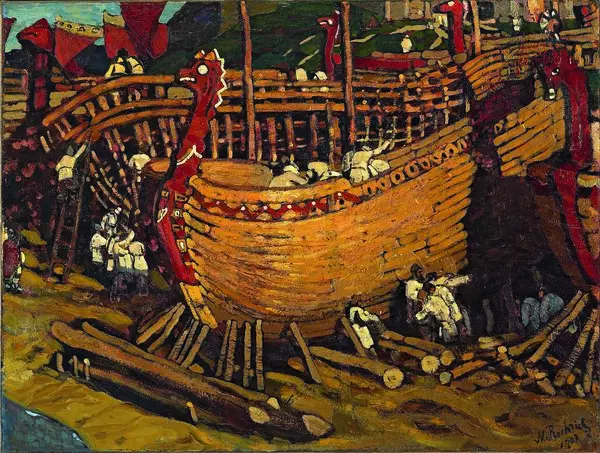

The artist Nicholas Konstantinovich Roerich decided to compose the panel “A Good Tree Has Grown” in an unusual way. If it is placed next to an identical paired work, a tree is formed in the middle. The halves cut off by the edges of the canvas invite the viewer’s imagination.

The Tree of Life has a powerful spreading crown with flowers and fruits that birds peck at. An endless garden full of trees is figuratively represented. In the lower part of the panel, the artist created a pattern in which one can distinguish the original folk principles.

Pictorial epics had previously been found in ancient Russian religious art. It featured animals, birds, griffins, pagan centaurs — creatures that were found on pre-Christian animal-style jewelry — depicted as decorations. The intertwining of Christianity and paganism symbolized tolerance.

The pattern in the lower part of the painting can be perceived as a foundation, a tradition from which powerful trees have grown, and now between them springs the future. In Art Nouveau, patterns were one of the main expressive means that gave completeness to the compositional structure of works.

The color of the panel is not similar to the color of the paints, which Nicholas Konstantinovich Roerich often resorted to, the ones that amaze with their saturation, brightness of combinations and sonority of tone. For this series of works, the Russian artist chose a tempera, pale olive background.

Russian art historian

and professor of the International Slavic Academy Evgeny Palladievich Matochkin

wrote that in the panel “A Good Tree Has Grown” the color “no longer so much

colors objects as highlights them from the inside. Birds and fruits, painted with

light touches of a ‘dry brush’ in red meerkat on a dim smoky background, seem

to consist of a fiery substance. Its flashes flicker like flames, creating the

effect of burning colors. <…>

The material form and volume completely disappear, leaving only a kind of

luminous primordial idea radiating its glowing red-hot fluids into space. The symbolism of the

image begins to be perceived not so much on the basis of sensory experience as

in a state of religious ecstasy.“