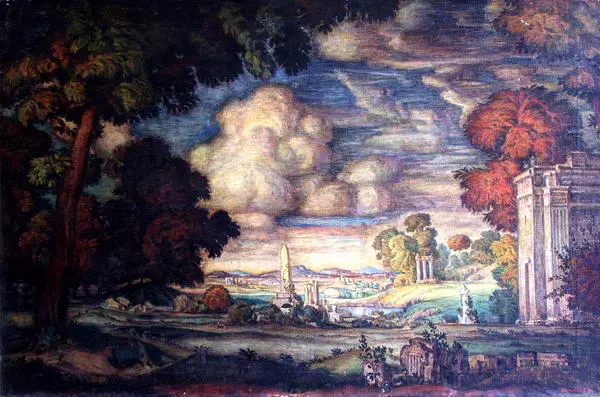

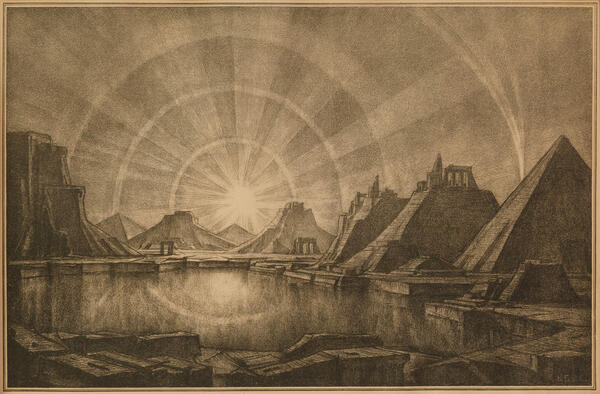

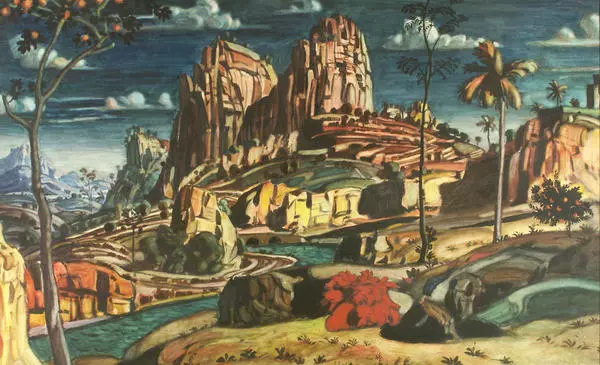

In the collection of the Sevastopol Art Museum named after Mikhail Pavlovich Kroshitsky, there are two landscapes by Konstantin Fyodorovich Bogaevsky — “The Last Rays” and “Southern Country”. One is about the distant past, the other a kind of prophecy of the distant future. The landscapes are referred to different stages in the artist’s work. In “The Last Rays”, the decorative form, the origins of which can be found in the art of his teacher Arkhip Kuindzhi, is combined with the “tragedy of thought”. The painting conveys an almost oppressive silence. The silence of the earth gives a sense of fragility, short-lived peoples and civilizations: there are only wild stones on the ground, reminiscent of the Tatar burial hills, and white clouds, floating in the sky as if slightly alarmed, but still indifferent.

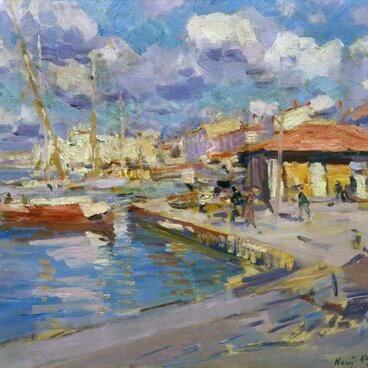

The whole artistic life of the Crimean artist Konstantin Bogaevsky (1872–1943) was associated with Feodosia, the city filled with the glory of Ivan Konstantinovich Aivazovsky. The artistic atmosphere that always reigned there, invited to art, yet constrained, and often just suppressed independent creativity. Therefore, even such a talented artist as Bogaevsky had to find a theme of his own. Probably, the very nature of the Crimea, its geological structure — desert saline steppes, wormwood hills of Koktebel, “sullen” rocks with scanty vegetation, as well as the sea, the ruins of Scythian, Greek, and Genoese colonies — pointed Bogaevsky to a theme of painting. They helped to find the proper pictorial form for paintings — monumental, majestic, and calm, appearing static, but sometimes filled with inner drama.

The Crimea was commonly treated as an exotic resort land. Numerous artists, coming to the south to rest, did not bother themselves with any research and just sent to all corners of Russia “greetings from the Crimea” — postcard views with a strip of sea, a cypress tree, and the scorching sun. Yet, at the same time, at the beginning of the 20th century, many educated people of Russia — scientists, poets, artists — regarded the Crimea as “a piece of antiquity”, as “a corner saturated with its spirit and bringing antique dreams”. It was then that researchers began to conduct systematic excavations of the Greek colonies of Chersonesus and Pantikapaion. For Bogaevsky, it was not so much the scientific evidence of archaeological discoveries that was important, as new opportunities for dreams and conjectures.