In 1870s, Konstantin Makovsky traveled around Serbia and Egypt. Those trips made a notable contribution into his world perception and his art. Social problems and psychological dilemmas were replaced with scaled-down subjects and intimate images. Besides, the focus of his paintings shifted towards the form and the color.

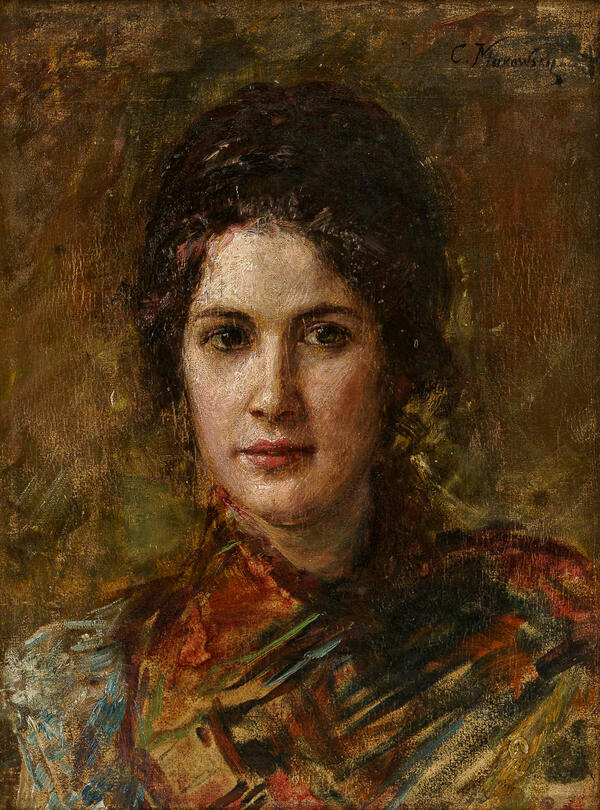

The Head of a Girl painted in 1880s can serve as an example of that modified approach to art. The artist painted the portrait with oil on wood. The background is painted with intentionally negligent brushstrokes for the sake of creating an effect of unsteadiness and even fluctuation. This is a quite common solution for plotless romantic sketches used for interior decoration.

In the center of the composition, there is a young lady in a motley flamboyant dress with a high neckline. Long hair of the girl is let down the shoulders instead of being set into a stylish hairdo. Her look is direct but slightly distrustful. Her cheeks are covered with modest blush. All these details exemplify the atmosphere of exoticism and mysteriousness.

It is noteworthy that the painter perfectly succeeded with it. The point is that art experts are still not sure of the identity of the model. Supposedly, the artist’s model for The Head of a Girl was Alexandra Bugayeva, as she more than once acted as the painter’s muse, including for his paintings The Boyar Wedding Feast of the 17th Century dated 1883 and Leading to the Altar dated 1890.

In late 19th century, Konstantin Makovsky was at the peak of his financial success. A lot of society ladies and gentlemen wanted to supplement their private collections or revamp the walls of their chambers with his paintings.

This was mainly due to the fact that the genre of ornamental portraits did not imply realistic representation of human appearance. On the contrary, the person was pictured younger, healthier and more glamorous than he or she really was. Especially popular were idealized female characters.

That man had an eye for beauty. Konstantin Makovsky was married three times: to Elena Burkova, to Yulia Letkova and Maria Matavtina. Each of his wives was recognized exceptionally attractive by his contemporaries. For example, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, a famous writer, had a liking for the second wife.

Nevertheless, the glory of the portrait artist was brought along not only by his evident talent, but also by appropriate publicity, like publishing the works in the Neva, the most circulated journal in the pre-revolutionary Russia, or the painter’s visit to the World Fair in France.

The Head of a Girl painted in 1880s can serve as an example of that modified approach to art. The artist painted the portrait with oil on wood. The background is painted with intentionally negligent brushstrokes for the sake of creating an effect of unsteadiness and even fluctuation. This is a quite common solution for plotless romantic sketches used for interior decoration.

In the center of the composition, there is a young lady in a motley flamboyant dress with a high neckline. Long hair of the girl is let down the shoulders instead of being set into a stylish hairdo. Her look is direct but slightly distrustful. Her cheeks are covered with modest blush. All these details exemplify the atmosphere of exoticism and mysteriousness.

It is noteworthy that the painter perfectly succeeded with it. The point is that art experts are still not sure of the identity of the model. Supposedly, the artist’s model for The Head of a Girl was Alexandra Bugayeva, as she more than once acted as the painter’s muse, including for his paintings The Boyar Wedding Feast of the 17th Century dated 1883 and Leading to the Altar dated 1890.

In late 19th century, Konstantin Makovsky was at the peak of his financial success. A lot of society ladies and gentlemen wanted to supplement their private collections or revamp the walls of their chambers with his paintings.

This was mainly due to the fact that the genre of ornamental portraits did not imply realistic representation of human appearance. On the contrary, the person was pictured younger, healthier and more glamorous than he or she really was. Especially popular were idealized female characters.

That man had an eye for beauty. Konstantin Makovsky was married three times: to Elena Burkova, to Yulia Letkova and Maria Matavtina. Each of his wives was recognized exceptionally attractive by his contemporaries. For example, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, a famous writer, had a liking for the second wife.

Nevertheless, the glory of the portrait artist was brought along not only by his evident talent, but also by appropriate publicity, like publishing the works in the Neva, the most circulated journal in the pre-revolutionary Russia, or the painter’s visit to the World Fair in France.