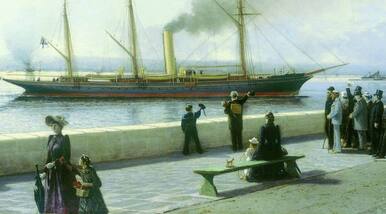

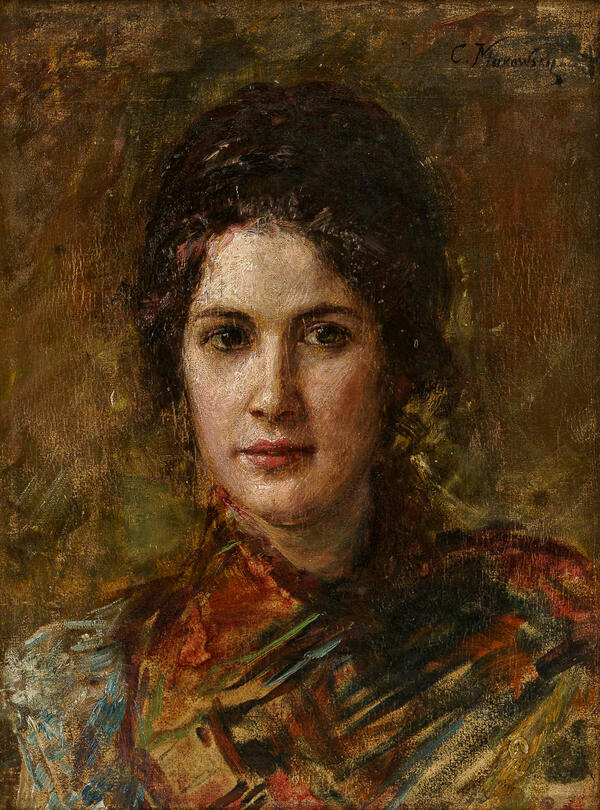

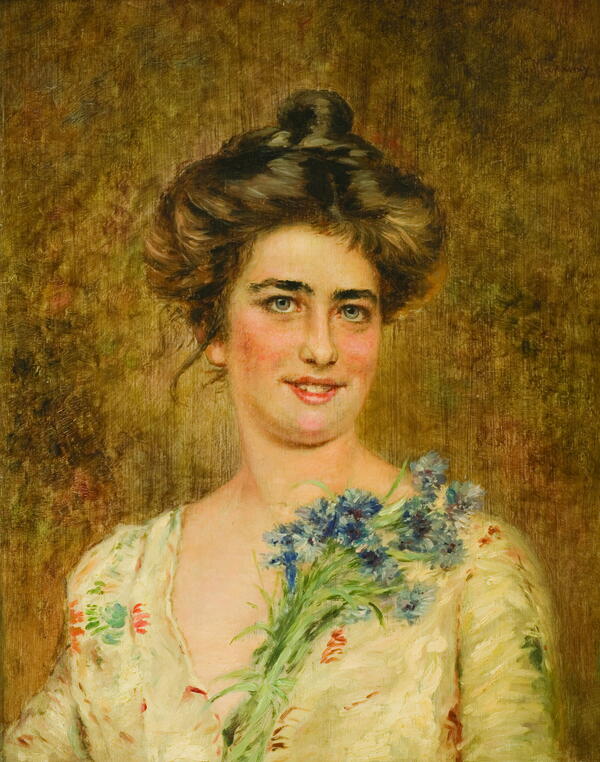

Konstantin Yegorovich Makovsky is one of the most prominent Russian painters and portraitists of the 19th century. He studied at Moscow School of Arts, Sculpture and Architecture, and then in the Imperial Academy of Arts in Saint Petersburg. He was on the first participants of the exhibitions of Itinerants artistic association.

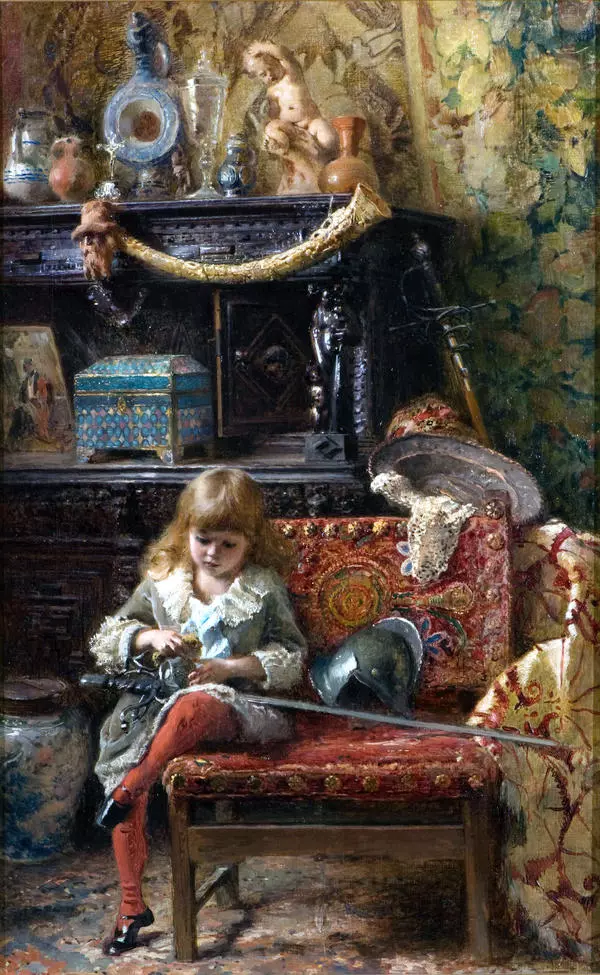

In 1880-s and 1890-s, Konstantin Makovsky turned to the subjects of pre-Peter Russia. This topic was very popular among artists at that time. The masters were rereading historic research materials about old Russian living; they used Russian museums funds and private collections for studying weapons, utensils, clothes and furniture of the 16th-17th centuries.

It should be noted that some painters had a rather simplified approach to historic realities. They put special focus on old items, and the personages were just for demonstrating them. Their paintings often looked like showcases exhibiting typical boyars, sextons and Streltsy (Russian guardsmen).

The painting Getting Married depicts the pre-wedding preparation of the bride in the boyar family of the 16th-17th centuries. The action takes place in the ample rooms on the top floor of the tower-house. Those were the rooms for women and children before 7 years of age. Women are combing the bride’s plait as a symbol of saying goodbye to her maidenhood. In the Old Russia, young girls were wearing one plait, and married women had their hair styled in two plaits.

A girl is sitting at the bride’s feet looking bewitchingly into her face. Their clasped hands symbolize the maidenhood and marriage. Women surrounding the bride wear ceremonial headgear – the kokoshniks (traditional headbands). The man standing in the doorway wearing a white towel tied across his left shoulder is druzhka, the Russian word for the best man. He represents the groom and brings a little chest with his presents to the bride. His most important objective during the wedding ceremony was to protect the newlyweds from bad spell and evil eye.

Makovsky thoroughly reproduced the details of the old interior, but he also added the household realities familiar to the public of the 19th century: in the pre-Peter Russian households did not have floor carpets or window curtains. Even in wealthy families, carpets were believed to be too beautiful and expensive to walk on them. The bride wearing white (the color for the deadly shroud) would have caused the strongest shock; in those days, brides wore red pinafore dresses.

The overall palette of the painting is a bright, but very much fragmented combination of colorful spots. In his future work, Makovsky was able to overcome such motley.

In 1880-s and 1890-s, Konstantin Makovsky turned to the subjects of pre-Peter Russia. This topic was very popular among artists at that time. The masters were rereading historic research materials about old Russian living; they used Russian museums funds and private collections for studying weapons, utensils, clothes and furniture of the 16th-17th centuries.

It should be noted that some painters had a rather simplified approach to historic realities. They put special focus on old items, and the personages were just for demonstrating them. Their paintings often looked like showcases exhibiting typical boyars, sextons and Streltsy (Russian guardsmen).

The painting Getting Married depicts the pre-wedding preparation of the bride in the boyar family of the 16th-17th centuries. The action takes place in the ample rooms on the top floor of the tower-house. Those were the rooms for women and children before 7 years of age. Women are combing the bride’s plait as a symbol of saying goodbye to her maidenhood. In the Old Russia, young girls were wearing one plait, and married women had their hair styled in two plaits.

A girl is sitting at the bride’s feet looking bewitchingly into her face. Their clasped hands symbolize the maidenhood and marriage. Women surrounding the bride wear ceremonial headgear – the kokoshniks (traditional headbands). The man standing in the doorway wearing a white towel tied across his left shoulder is druzhka, the Russian word for the best man. He represents the groom and brings a little chest with his presents to the bride. His most important objective during the wedding ceremony was to protect the newlyweds from bad spell and evil eye.

Makovsky thoroughly reproduced the details of the old interior, but he also added the household realities familiar to the public of the 19th century: in the pre-Peter Russian households did not have floor carpets or window curtains. Even in wealthy families, carpets were believed to be too beautiful and expensive to walk on them. The bride wearing white (the color for the deadly shroud) would have caused the strongest shock; in those days, brides wore red pinafore dresses.

The overall palette of the painting is a bright, but very much fragmented combination of colorful spots. In his future work, Makovsky was able to overcome such motley.