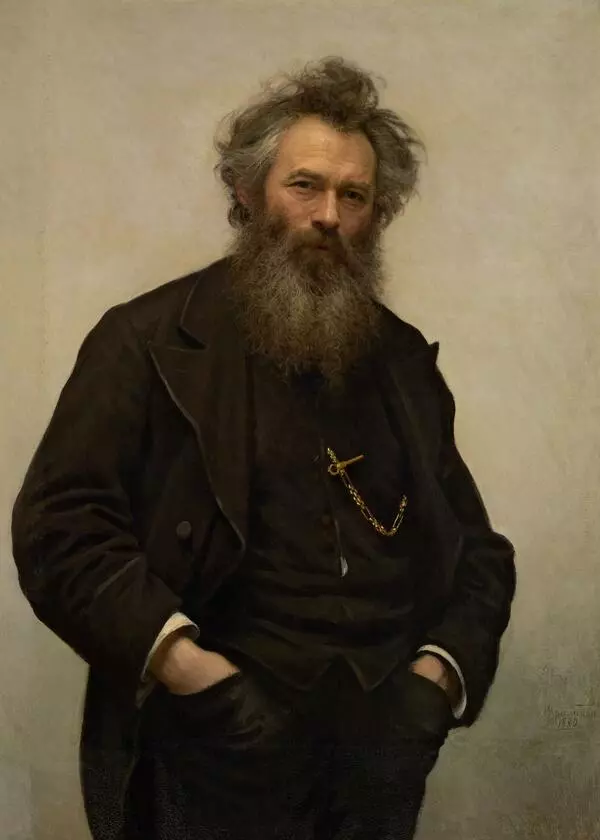

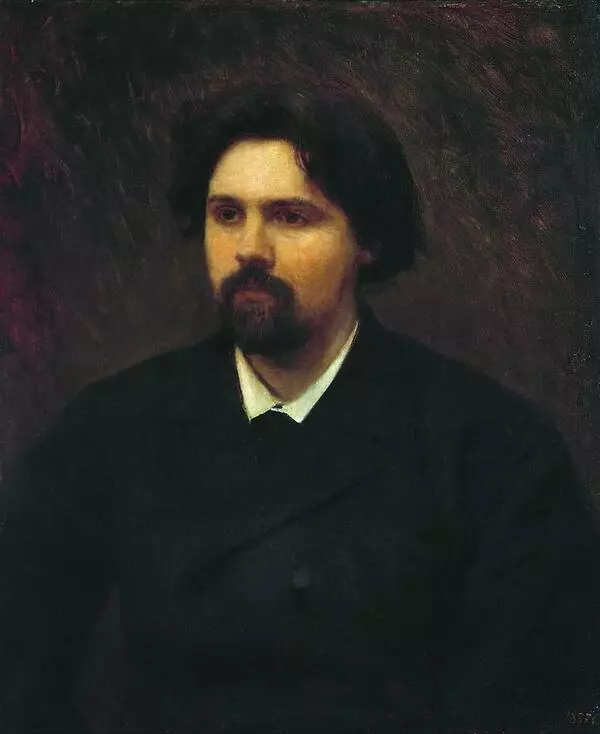

Ivan Nikolaevich Kramskoi not only stood at the origins of many changes in the art of the second half of the 19th century - we can say that he himself created them directly. The initiator of the sensational ‘Revolt of Fourteen’, the ideological inspirer of the Company of Itinerant Art Exhibitions, Kramskoi, thanks to his ascetic work, made him one of the most powerful and resilient creative organizations in the history of Russian art.

The famous artist Alexander Benois admitted: ‘It is very likely that if there hadn’t been Kramskoi, there would have been […] perhaps no direction, since the talented young artists scattered, without firm convictions, without a program, would have gone unnoticed […]. Kramskoi’s mind and energy united them all into one whole, gave their intentions one common, definite goal, and developed a doctrine for them to stand for.’

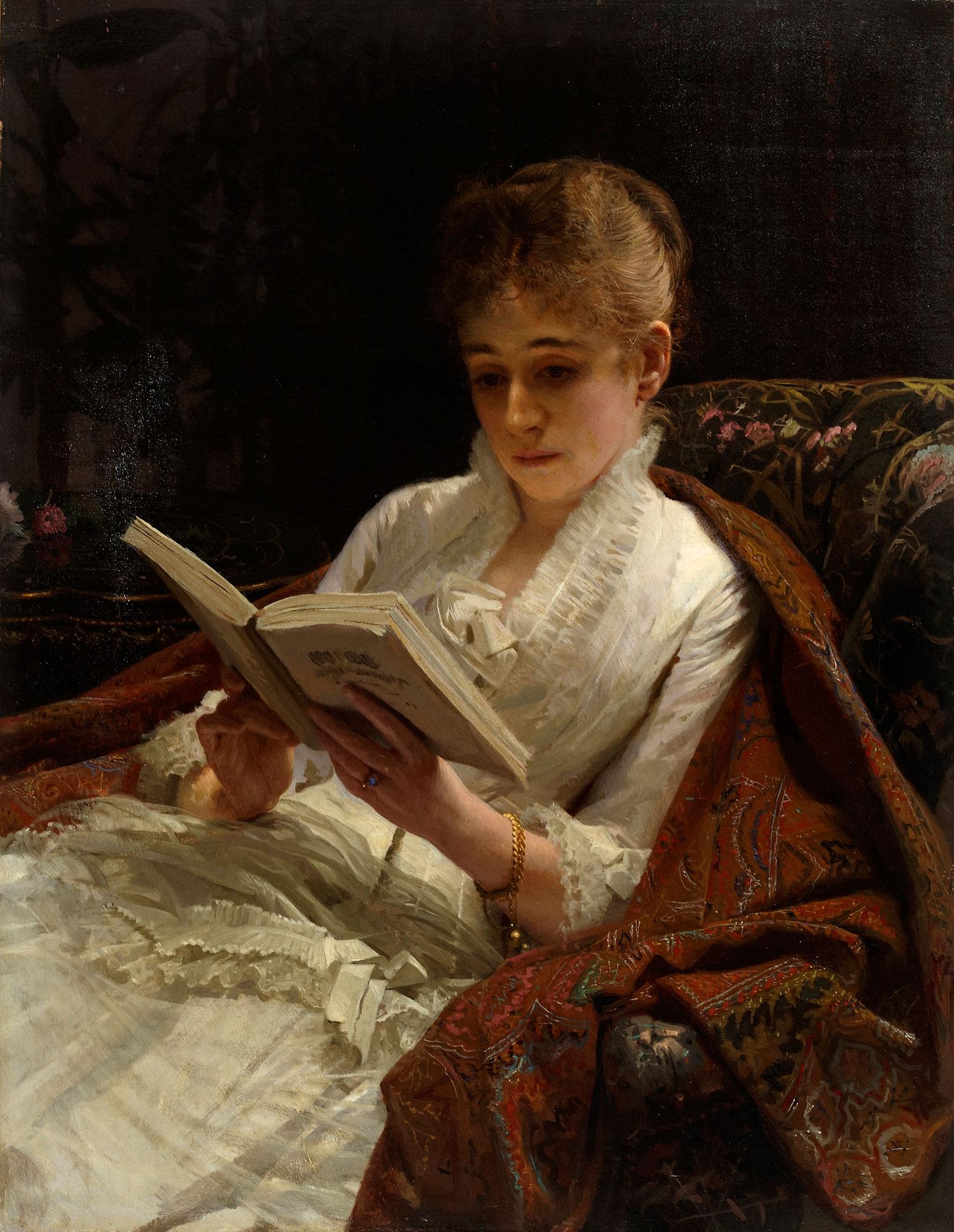

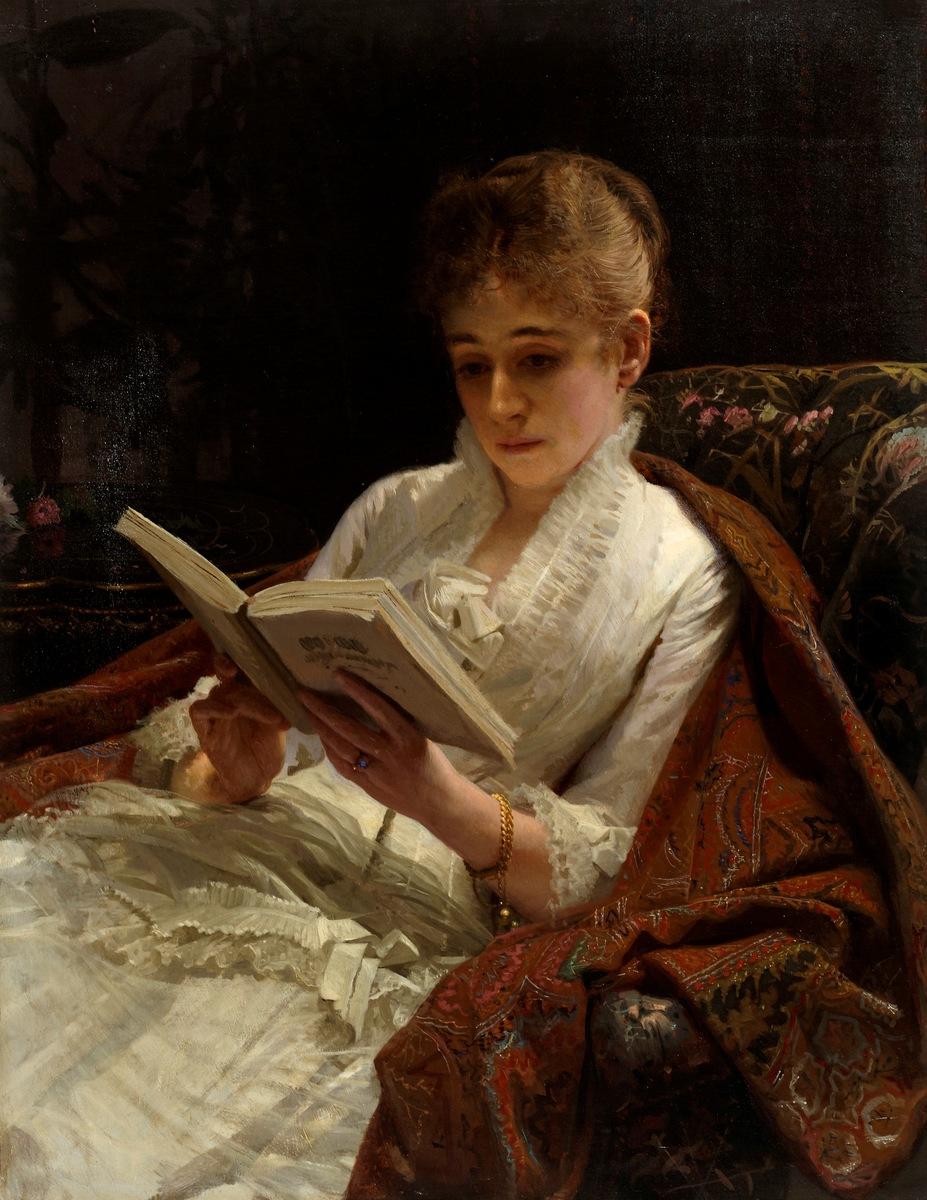

Kramskoi’s own work was not so highly appreciated by art critics, but all of them recognized his talent as an outstanding portrait painter. This is evidenced by the presented portrait, which allegedly depicts Louise Horatsievna Ginzburg - the daughter of Horace Osipovich Ginzburg, the owner of the largest banking and industrial house in St. Petersburg, a well-known philanthropist.

Kramskoi was friends with the Ginzburg family, often visited their house, and painted portraits of the owner. Among the artist’s correspondence there is a letter dated September 27, 1884, where he writes to Ginzburg that he also has two portraits of Louise Horatievna. Researchers believe that one of them may be the ‘Portrait of a Woman’ from the collection of the Yekaterinburg Museum of Fine Arts.

The image of the baroness should be recognized as one of the best female images created by Kramskoi. Often being in the house and observing the habits of the household, the master well studied the characteristic, natural posture and facial expression of the portrayed, completely immersed in reading. An exquisite dress, a rich shawl, finely selected accessories characterize her as a woman of high society, and an accurate drawing that reproduces the volumes, their careful modeling with chiaroscuro, soft color transitions ensure the integrity and unity of the portrait image.

The famous artist Alexander Benois admitted: ‘It is very likely that if there hadn’t been Kramskoi, there would have been […] perhaps no direction, since the talented young artists scattered, without firm convictions, without a program, would have gone unnoticed […]. Kramskoi’s mind and energy united them all into one whole, gave their intentions one common, definite goal, and developed a doctrine for them to stand for.’

Kramskoi’s own work was not so highly appreciated by art critics, but all of them recognized his talent as an outstanding portrait painter. This is evidenced by the presented portrait, which allegedly depicts Louise Horatsievna Ginzburg - the daughter of Horace Osipovich Ginzburg, the owner of the largest banking and industrial house in St. Petersburg, a well-known philanthropist.

Kramskoi was friends with the Ginzburg family, often visited their house, and painted portraits of the owner. Among the artist’s correspondence there is a letter dated September 27, 1884, where he writes to Ginzburg that he also has two portraits of Louise Horatievna. Researchers believe that one of them may be the ‘Portrait of a Woman’ from the collection of the Yekaterinburg Museum of Fine Arts.

The image of the baroness should be recognized as one of the best female images created by Kramskoi. Often being in the house and observing the habits of the household, the master well studied the characteristic, natural posture and facial expression of the portrayed, completely immersed in reading. An exquisite dress, a rich shawl, finely selected accessories characterize her as a woman of high society, and an accurate drawing that reproduces the volumes, their careful modeling with chiaroscuro, soft color transitions ensure the integrity and unity of the portrait image.