Aristarkh Lentulov was a Russian painter, one of the founders of the famous association of avant-garde artists ‘Jack of Diamonds’.

Lentulov was born in Penza Governorate and from an early age dreamed of becoming an artist. At first, he entered the Penza Art School, then the Kiev Art School, and took exams at the Academy of Arts in St. Petersburg, but could not stay for a long time at any of the educational institutions. Teachers criticized him because of his passion for experimentations, and the artist often argued with them and even tried to correct their own works instead.

In 1908, Lentulov moved to Moscow and met artists Mikhail Larionov, Pyotr Konchalovsky and Alexander Kuprin. Two years later, they organized an exhibition called ‘The Jack of Diamonds’. It presented paintings in different styles. The artists collectively denounced salon art, academism and realism of the 19th century. The exhibition received negative reviews, only poet Maximilian Voloshin praised the displayed works. He wrote that he saw ‘a lot of true talent’ in the paintings.

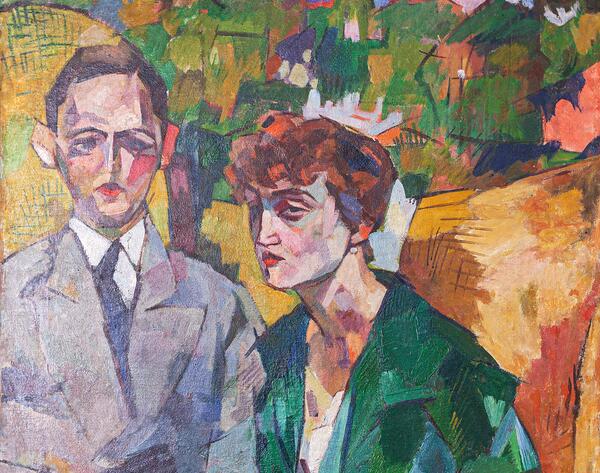

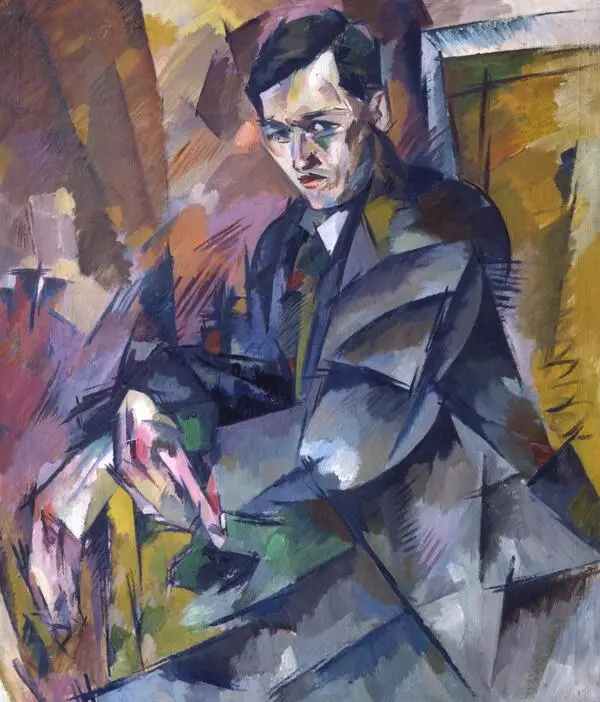

The ‘Double portrait’ by Aristarkh Lentulov expressively demonstrates the attitude of the ‘Jack of Diamonds’ artists to shape and color. This work has been reproduced in many books published in recent years about the Russian avant-garde. After his trip to Paris in 1911, the artist developed an interest in the creative discoveries of Paul Cézanne and Cubo-futurists. At the same time, he persistently worked on his own style, experimenting with colors and shapes of objects, for example, depicting three-dimensional objects as flat ones. French artists called his works ‘cubism a la ruse’.

Lentulov organically introduced Cubist elements into the pictorial fabric of this portrait. A certain hint of the canvas’s depth is provided by the different interpretation of male and female figures. The female figure, pushed forward, is created by clearer areas of saturated shades of green. The figure of a man in the background is painted with spots of gray with the most complex shades without clear contouring. The overall background consists of separate sections of additional colors: yellows and blues, reds and greens. Their bold juxtapositions and the sharpness of contrasts turn the painting into a mosaic, practically depriving it of life-like forms.

‘I resist pale painting’, the artist said. For the most daring canvases, he used the kaleidoscope principle — an arbitrary combination of colors — as an artistic solution. For the more restrained ones, such as the portrait from the museum collection, the kaleidoscope principle is only partially applied.

Aristarkh Lentulov believed that a photographic, realistic depiction of people is not necessary:

Lentulov was born in Penza Governorate and from an early age dreamed of becoming an artist. At first, he entered the Penza Art School, then the Kiev Art School, and took exams at the Academy of Arts in St. Petersburg, but could not stay for a long time at any of the educational institutions. Teachers criticized him because of his passion for experimentations, and the artist often argued with them and even tried to correct their own works instead.

In 1908, Lentulov moved to Moscow and met artists Mikhail Larionov, Pyotr Konchalovsky and Alexander Kuprin. Two years later, they organized an exhibition called ‘The Jack of Diamonds’. It presented paintings in different styles. The artists collectively denounced salon art, academism and realism of the 19th century. The exhibition received negative reviews, only poet Maximilian Voloshin praised the displayed works. He wrote that he saw ‘a lot of true talent’ in the paintings.

The ‘Double portrait’ by Aristarkh Lentulov expressively demonstrates the attitude of the ‘Jack of Diamonds’ artists to shape and color. This work has been reproduced in many books published in recent years about the Russian avant-garde. After his trip to Paris in 1911, the artist developed an interest in the creative discoveries of Paul Cézanne and Cubo-futurists. At the same time, he persistently worked on his own style, experimenting with colors and shapes of objects, for example, depicting three-dimensional objects as flat ones. French artists called his works ‘cubism a la ruse’.

Lentulov organically introduced Cubist elements into the pictorial fabric of this portrait. A certain hint of the canvas’s depth is provided by the different interpretation of male and female figures. The female figure, pushed forward, is created by clearer areas of saturated shades of green. The figure of a man in the background is painted with spots of gray with the most complex shades without clear contouring. The overall background consists of separate sections of additional colors: yellows and blues, reds and greens. Their bold juxtapositions and the sharpness of contrasts turn the painting into a mosaic, practically depriving it of life-like forms.

‘I resist pale painting’, the artist said. For the most daring canvases, he used the kaleidoscope principle — an arbitrary combination of colors — as an artistic solution. For the more restrained ones, such as the portrait from the museum collection, the kaleidoscope principle is only partially applied.

Aristarkh Lentulov believed that a photographic, realistic depiction of people is not necessary: