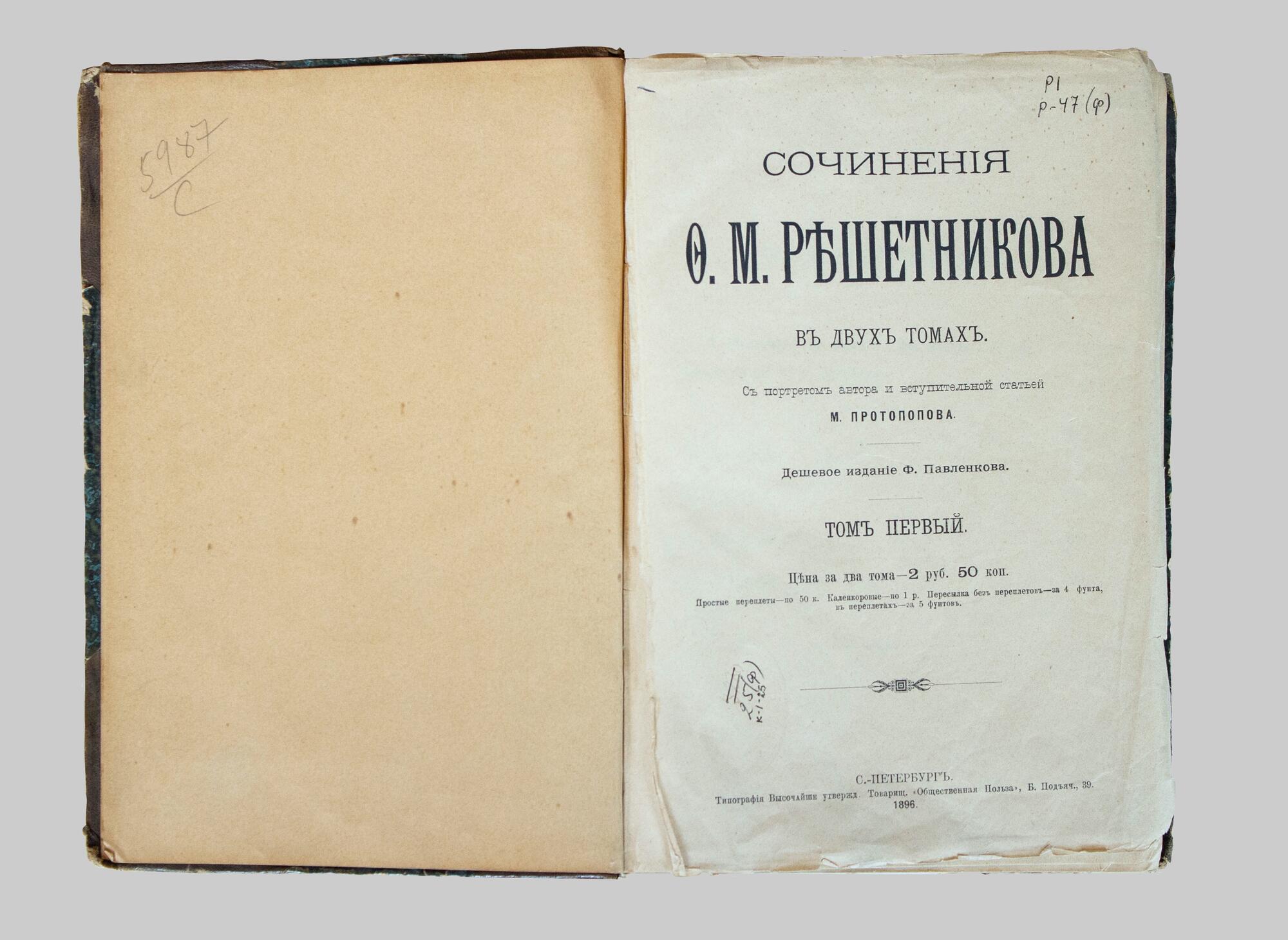

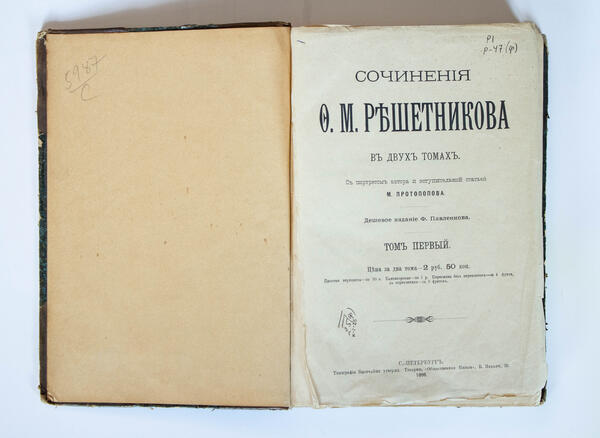

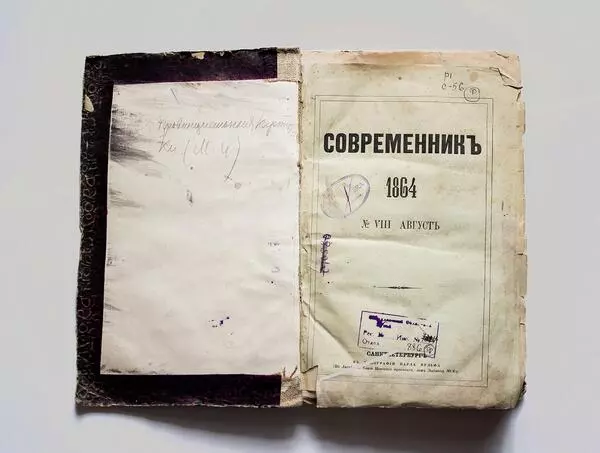

The exposition contains the first volume of the collected works by the Ural writer and essayist Fyodor Reshetnikov, which was published in 1896. The book includes a novel titled ‘Someplace Better’ that focuses on the life of miners. The novel was conceived in 1866, and it took the writer two years to complete it. Reshetnikov began writing Part Two while in Brest and finished it in St. Petersburg. The first chapters appeared in the literary journal Otechestvennye Zapiski (literally: Homeland Notes) around the same time. The novel was edited by MikhaIl Saltykov-ShchedrIn, who had received it in Ryazan. Having perused the manuscript, Saltykov-Shchedrin gave it a positive review, though later editing out a sizable chunk of the text.

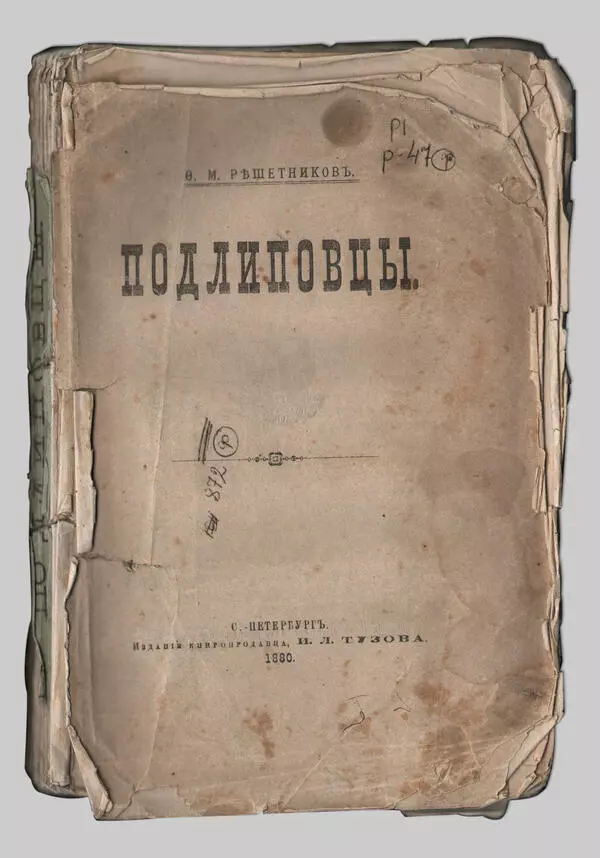

In 1868, Reshetnikov received an offer to publish ‘Someplace Better’ as a standalone book. The proposal came from the publisher, who had released another work by Reshetnikov the year before. It was a novella about the fate of the Perm peasants, titled ‘Podlipovtsy’. The writer charged 1,500 rubles for the novel. The novel was published as a standalone book in 1869. What exactly happened to the manuscript after the time it had spent in the Otechestvennye Zapiski editorial office, is unknown. The writer’s archive contains only a few draft notes and notes related to the text.

Reshetnikov’s novel echoes Nikolay Nekrasov’s poem “Who Lives Well in Russia?” Both publications highlight the processes that took place in Russia following the abolition of serfdom, and both narrate the fate of ordinary people. According to Ivan Veksler, a scholar who studies Reshetnikov’s legacy, the writer ‘realized his intention to describe the life of free miners’.

In assessing the working conditions, Reshetnikov relied on essays and articles of the time, as well as on his own experience: the writer reportedly worked at a number of plants. Veksler notes that Reshetnikov’s novel captured the general characteristics of the Ural region: “The reform slashed the number of workers at factories and kicked <…> the unprofitable human resources out of the factory teams”.

The answer to the novel’s major question is partly formulated by its characters, Petrov and Karavaev: ‘They often asked each other the question: Where is better? <…> and both came to the conclusion that humans were designed to get food on their own, and since humans really didn’t need much, they would be quite satisfied and at peace if they weren’t hurt by those who sought pleasure’.

In 1868, Reshetnikov received an offer to publish ‘Someplace Better’ as a standalone book. The proposal came from the publisher, who had released another work by Reshetnikov the year before. It was a novella about the fate of the Perm peasants, titled ‘Podlipovtsy’. The writer charged 1,500 rubles for the novel. The novel was published as a standalone book in 1869. What exactly happened to the manuscript after the time it had spent in the Otechestvennye Zapiski editorial office, is unknown. The writer’s archive contains only a few draft notes and notes related to the text.

Reshetnikov’s novel echoes Nikolay Nekrasov’s poem “Who Lives Well in Russia?” Both publications highlight the processes that took place in Russia following the abolition of serfdom, and both narrate the fate of ordinary people. According to Ivan Veksler, a scholar who studies Reshetnikov’s legacy, the writer ‘realized his intention to describe the life of free miners’.

In assessing the working conditions, Reshetnikov relied on essays and articles of the time, as well as on his own experience: the writer reportedly worked at a number of plants. Veksler notes that Reshetnikov’s novel captured the general characteristics of the Ural region: “The reform slashed the number of workers at factories and kicked <…> the unprofitable human resources out of the factory teams”.

The answer to the novel’s major question is partly formulated by its characters, Petrov and Karavaev: ‘They often asked each other the question: Where is better? <…> and both came to the conclusion that humans were designed to get food on their own, and since humans really didn’t need much, they would be quite satisfied and at peace if they weren’t hurt by those who sought pleasure’.