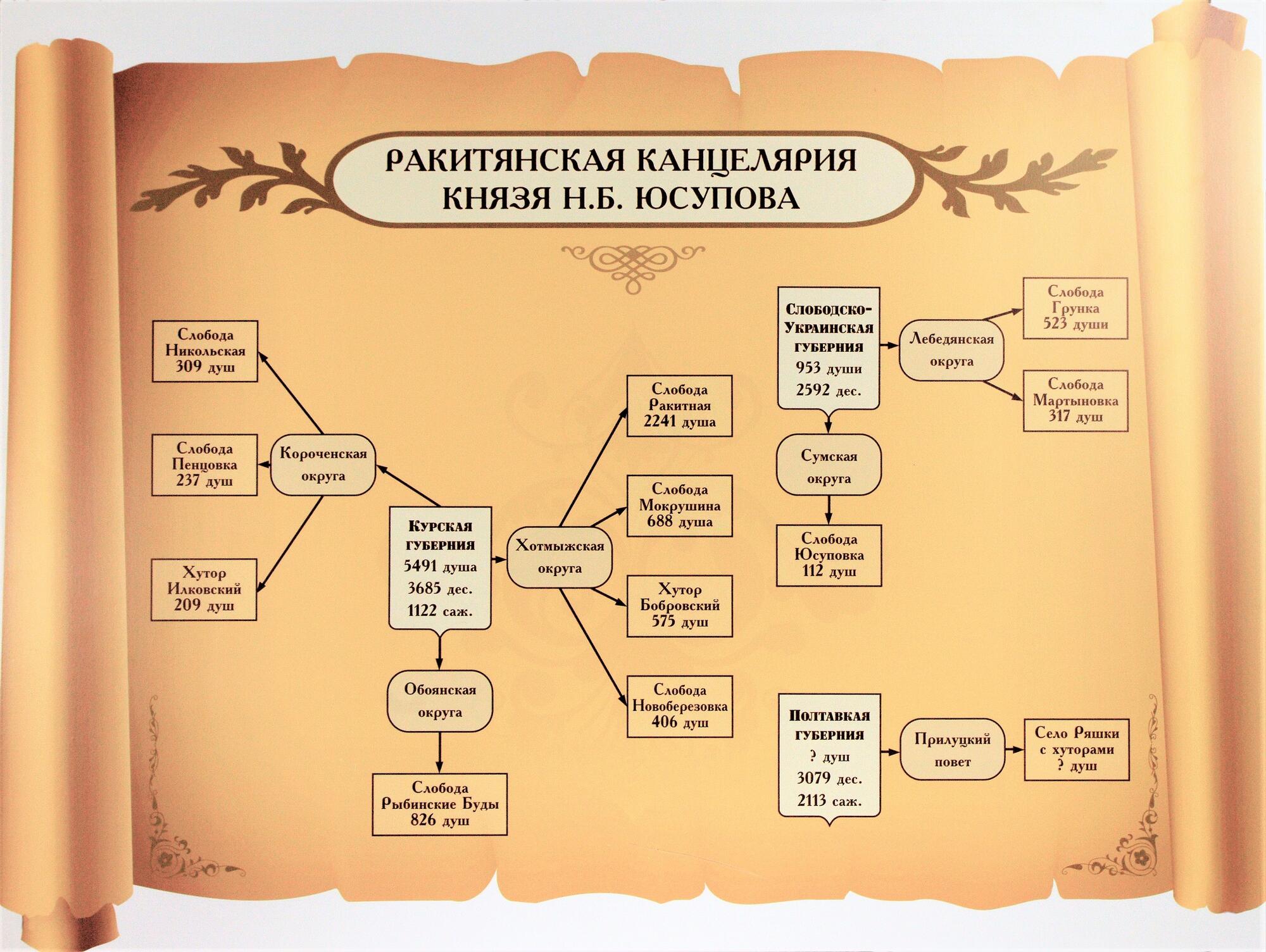

An administrative office is the word for a subdivision of the household that deals with accounting and documentation. The administrative office of Prince Nikolay Yusupov Sr. in Rakitnoye was a large institution. The “Main Administration of Rakitnoye” was located in Rakitnoye village; the number of Yusupov’s estates in different governorates — Kursk, Kharkov, Voronezh and Poltava — were subordinated to it.

Each estate had its own specialization of labor. Weaving flourished in Rakitnoye village. In 1797, the first carpet factory opened there, and the prince ordered Kondratovich, a clerk in the estate there, to “recruit from all departments of his estates those who are able to pay state taxes and my tribute, as well as orphans, who are used to work for the rich… All of them without a trace from all places to be drawn to the factory.”

In the archives of the Yusupov family, there are many documents that give an idea of the standard of living of these workers. The earliest paper refers to 1815 listing freelance courtiers, who worked in the karaseya (weaving), broadcloth, carpet, sewing and lace production.

For instance, the carpet factory employed 12 young apprentices and a 60-year-old supervisor, Anisya Kurochkina. The record says the workers were to receive “a salary of 5 rubles, 2 rubles and 82 kopecks a month for food, 3 parts of flour and 6 parts of groats”, as well as about 11 kilos of salt, 2 rubles for a cloak, 2 rubles for shirts, 1 ruble for a skirt and 3.5 meters of karaseya (a piece of rare woolen cloth) for other items. Apparently, female workers received 5 rubles in wages for a year of work and not monthly. In some cases, female workers were paid more; most likely, it depended on their qualifications.

Such an income was considered very low. The war with Napoleon in 1812 had a bad impact on the purchasing power of the ruble: in the capital, a kilo of rye flour cost 28 kopecks, while the best meat cost 1.5 rubles.

However, the prince could also assign additional payments to his female workers. The data of 1819 contain a report that a carpet-maker, Fedora Trusova, arrived at the carpet factory in Rakitnoye from Moscow. Noting her work as a supervisor, Prince Yusupov wrote to the manager:

Each estate had its own specialization of labor. Weaving flourished in Rakitnoye village. In 1797, the first carpet factory opened there, and the prince ordered Kondratovich, a clerk in the estate there, to “recruit from all departments of his estates those who are able to pay state taxes and my tribute, as well as orphans, who are used to work for the rich… All of them without a trace from all places to be drawn to the factory.”

In the archives of the Yusupov family, there are many documents that give an idea of the standard of living of these workers. The earliest paper refers to 1815 listing freelance courtiers, who worked in the karaseya (weaving), broadcloth, carpet, sewing and lace production.

For instance, the carpet factory employed 12 young apprentices and a 60-year-old supervisor, Anisya Kurochkina. The record says the workers were to receive “a salary of 5 rubles, 2 rubles and 82 kopecks a month for food, 3 parts of flour and 6 parts of groats”, as well as about 11 kilos of salt, 2 rubles for a cloak, 2 rubles for shirts, 1 ruble for a skirt and 3.5 meters of karaseya (a piece of rare woolen cloth) for other items. Apparently, female workers received 5 rubles in wages for a year of work and not monthly. In some cases, female workers were paid more; most likely, it depended on their qualifications.

Such an income was considered very low. The war with Napoleon in 1812 had a bad impact on the purchasing power of the ruble: in the capital, a kilo of rye flour cost 28 kopecks, while the best meat cost 1.5 rubles.

However, the prince could also assign additional payments to his female workers. The data of 1819 contain a report that a carpet-maker, Fedora Trusova, arrived at the carpet factory in Rakitnoye from Moscow. Noting her work as a supervisor, Prince Yusupov wrote to the manager: