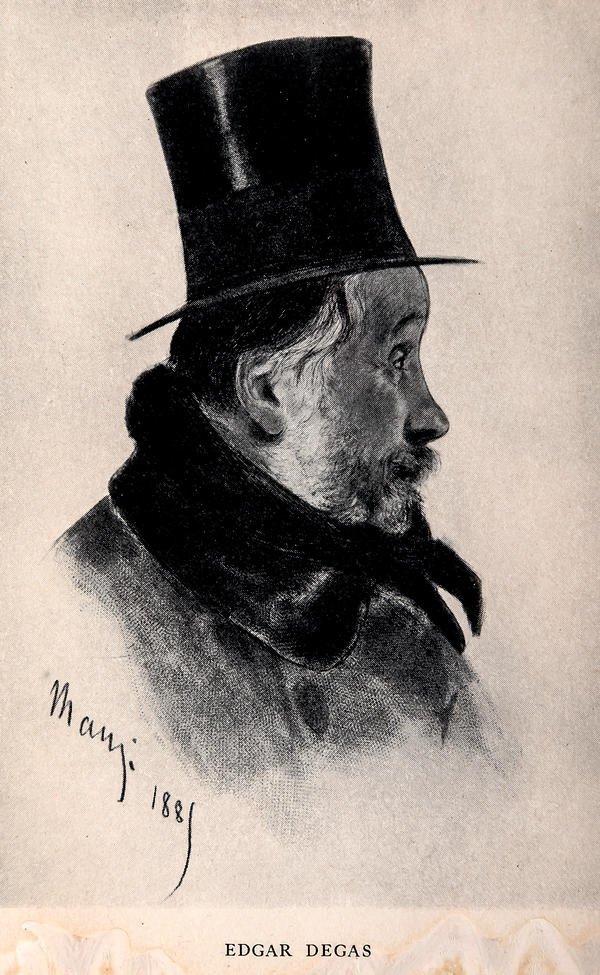

This profile portrait of the French painter Edgar Degas was created in 1885 by his friend, an artist, a typographer, and a pioneer of photomechanical printing: Michel Manzi (1849–1915).

The French post-impressionist Edgar Degas /de’ga/ was one of Sergei Eisenstein’s favorite artists. The director considered him an equal to titans of the Renaissance—El Greco, Titian, Tintoretto—and the masters of the New Time: Daumier, Van Gogh, and Valentin Serov. In his theoretical works and at lectures at All-Union State Institute of Cinematography, Eisenstein often referred to the works of Degas to illustrate the masterful composition skills of the artist, the way he combined different phases of movement in the gestures of the characters, and how the ‘impressionistically captured instantaneousness of immediate impression’ and the harmony of the general structure was balanced in the paintings. Sergei Eisenstein believed that his students could learn to build compositions of frames Degas’s paintings; to “open” the frame of the image, and let the viewers perceive the objects outside of the picture’s scope.

Eisenstein amassed a big collection of Degas' albums and monographs about him in Russian, French, English and German; he carefully read memoirs about Edgar Degas and artist’s own letters in order to understand his character, his creative aspirations, his life circumstances, and friendships. A complex approach to the works and personal affairs of the artist have allowed Sergei Eisenstein to show that Degas' stylistically innovative masterpieces had predecessors that developed similar principles, and that the artist’s discoveries were rooted in profound psychological premises. Eisenstein’s method became a completely new approach to analyzing the composition of a work and the creative process itself. His analysis of Degas’s ‘Bathing women’ series of paintings has foretold some of the ideas and methods in the history and theory of art of the late XX and early XXI centuries.

In Eisenstein’s apartment, a portrait of Degas hung in the library right beneath a photograph of the 19th-century French actor FrederIc LemAItre. The director believed that with the help of new technology cinema realizes the oldest aspiration of art — to preserve moving forms of life in the unity of space and time. Many expressive means of cinematography carry on the centuries of worlds' cultural heritage.

The French post-impressionist Edgar Degas /de’ga/ was one of Sergei Eisenstein’s favorite artists. The director considered him an equal to titans of the Renaissance—El Greco, Titian, Tintoretto—and the masters of the New Time: Daumier, Van Gogh, and Valentin Serov. In his theoretical works and at lectures at All-Union State Institute of Cinematography, Eisenstein often referred to the works of Degas to illustrate the masterful composition skills of the artist, the way he combined different phases of movement in the gestures of the characters, and how the ‘impressionistically captured instantaneousness of immediate impression’ and the harmony of the general structure was balanced in the paintings. Sergei Eisenstein believed that his students could learn to build compositions of frames Degas’s paintings; to “open” the frame of the image, and let the viewers perceive the objects outside of the picture’s scope.

Eisenstein amassed a big collection of Degas' albums and monographs about him in Russian, French, English and German; he carefully read memoirs about Edgar Degas and artist’s own letters in order to understand his character, his creative aspirations, his life circumstances, and friendships. A complex approach to the works and personal affairs of the artist have allowed Sergei Eisenstein to show that Degas' stylistically innovative masterpieces had predecessors that developed similar principles, and that the artist’s discoveries were rooted in profound psychological premises. Eisenstein’s method became a completely new approach to analyzing the composition of a work and the creative process itself. His analysis of Degas’s ‘Bathing women’ series of paintings has foretold some of the ideas and methods in the history and theory of art of the late XX and early XXI centuries.

In Eisenstein’s apartment, a portrait of Degas hung in the library right beneath a photograph of the 19th-century French actor FrederIc LemAItre. The director believed that with the help of new technology cinema realizes the oldest aspiration of art — to preserve moving forms of life in the unity of space and time. Many expressive means of cinematography carry on the centuries of worlds' cultural heritage.