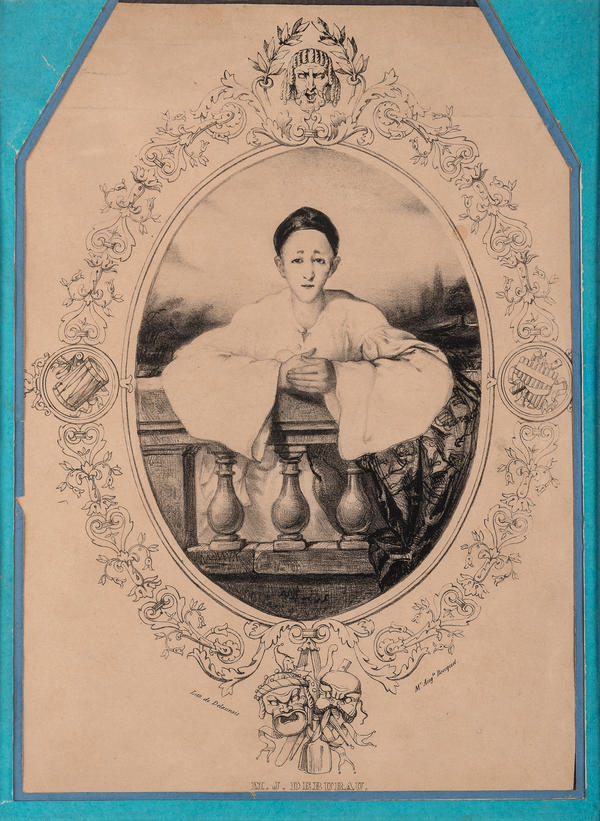

This portrait by AugUste Bouquet /bu’kei/ depicts the mime Jean-BaptIste-Gaspard /gas’par/ Deburau /debju’ro/ (1796–1846), one of the leading figures of the Parisian boulevard theater “FunambUEle” and creator of the famous Pierrot /pje’ro/ persona. Deburau revived the ancient pantomime and reintroduced the ‘eloquent silence’ to the theatre. His art and fame were promoted by the fact that at the beginning of the 19th century, only ‘silent’ performances were permitted at the Boulevard Temple: in 1806, Napoleon the First, fearing the ‘subversive’ influence of folk shows and their competition with the court theater, ordered to present only pantomimes, ballets and circus numbers on stage. But the plastic expressiveness of the pantomime actors turned out to be stronger than the outdated ‘high style’ of declamations in the Comédie Francaise theatre, and small boulevard theaters drew in the Parisian public. Even when Napoleon’s prohibition was lifted, and “talking” genres (melodrama, detective, folk comedy) were once again dominating the boulevard theatres, pantomimes — comic and lyrical — retained their popularity.

Contemporaries called Deburau “the greatest actor of his age.” He possessed a rare ability to combine humour and tragedy on stage, mixing the farcical with the lyrical. He turned a ramshackle performance that occupied the middle ground between theatre and circus, and turned it into “philosophy on stage”, accessible even to the simplest audiences. Deburau’s work was continued in the 20th century by the great comedians of silent films — Max Linder, Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, and others. Later, his traditions were revived in France by Jean-Louis Barrot and Marcel Marceau on stage, and by Jacques Tati and Pierre Etex in cinema.

Eisenstein knew and loved Deburau’s work as it was described to him by the actor’s contemporaries and theatre scholars in their studies. The image of the sad Pierrot, to whom has given psychological depth, appears in Deburau’s earliest theatrical sketches influenced by the Italian comedy of masks. Sergei Eisenstein was concerned with the issues of expressive movement from the earliest years of his career — the actor had to convey without words the deep movements and contradictions of the human soul. For that reason he often referred to Deburau’s works in his career as a film director as well as in his theoretical works and the lectures he gave at All-Union State Institute of Cinematography. Eisenstein had portraits of the great mime and his antipode friend FrederIc-LemAItre long before the French director MarcEl Carnet /kar’ne/ made his film Children of the Rayk (1945) about them.

Contemporaries called Deburau “the greatest actor of his age.” He possessed a rare ability to combine humour and tragedy on stage, mixing the farcical with the lyrical. He turned a ramshackle performance that occupied the middle ground between theatre and circus, and turned it into “philosophy on stage”, accessible even to the simplest audiences. Deburau’s work was continued in the 20th century by the great comedians of silent films — Max Linder, Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, and others. Later, his traditions were revived in France by Jean-Louis Barrot and Marcel Marceau on stage, and by Jacques Tati and Pierre Etex in cinema.

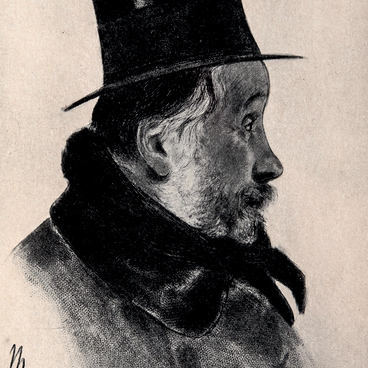

Eisenstein knew and loved Deburau’s work as it was described to him by the actor’s contemporaries and theatre scholars in their studies. The image of the sad Pierrot, to whom has given psychological depth, appears in Deburau’s earliest theatrical sketches influenced by the Italian comedy of masks. Sergei Eisenstein was concerned with the issues of expressive movement from the earliest years of his career — the actor had to convey without words the deep movements and contradictions of the human soul. For that reason he often referred to Deburau’s works in his career as a film director as well as in his theoretical works and the lectures he gave at All-Union State Institute of Cinematography. Eisenstein had portraits of the great mime and his antipode friend FrederIc-LemAItre long before the French director MarcEl Carnet /kar’ne/ made his film Children of the Rayk (1945) about them.