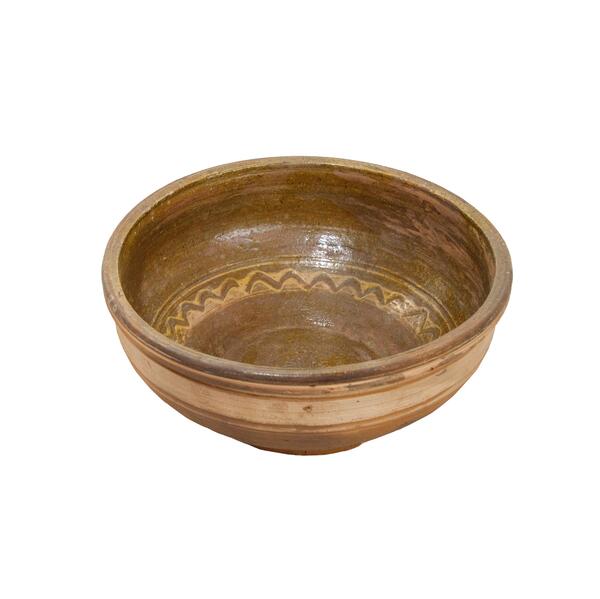

Kuzma Shitikhin, a potter from the village Shishkeevo, Ruzaevsky District, presented this lunch bowl to the museum in 1976. The bowl has a deep form and is made of light clay. Its inner surface is covered with lead coating — glazing. There is a carved ornament on the bottom and walls of the inner side of the bowl. In the center of the bottom, you can see a multibeam solar sign that is a symbol of the Universe. There is also a continuous wavy line on the walls. A milky colored band is depicted on the inner side of the bowl with liquid clay of different shades.

The first references about the Russian village Shishkeevo in the Republic of Mordovia date back to 1638. Until 1928, it was a part of the Insarsky District, Penza Province. Thanks to rich clay deposits of good quality, the village very soon became one of the pottery centers of the region, along with Bolshoi Kazarinov in Nizhny Novgorod Province, Sukhoi Karsun in Simbirsk Province, and Abashevo in Penza Province. “We are sitting on clay. Is it possible not to become a potter?” local craftsmen said.

Pottery was a seasonal craft in Shishkeevo. Most craftsmen worked in autumn, when farming was finished. Pottery was a family business. Children were taught to make pottery from the age of 8-10. Whole dynasties of craftsmen worked in the village. Shitikhins, Lazarevs, Lyautkins, Musyrkins were among them.

Women helped prepare clay, load the wares into the furnace, and grind pigments for the glaze. Clay used to be dug in late autumn. Then it was kneaded by feet and left to freeze. A necessary amount of clay was brought in the hut and put under the benches and on the shelves. As the clay thawed, it was mixed with water and kneaded by hands until clay turn into homogeneous mass.

Until 1918, Shishkeevo craftsmen used hand-spun pottery wheels. First of all, the walls of pots and dishes were made up with special coils, and then they were worked on with a wooden knife, while the wheel was rotated with one hand. In 1918, several families of potters from Samara Province came to the village and brought a new kick wheel technology. The earthenware was pulled on it from a single piece of clay.

The finished dishes had to be dried during 2-4 days, and then they were fired for 4-8 hours in Russian stoves at a temperature of 600-700 degrees, on the hearthstone that is the lower surface of the stove. Goods made by the Shishkeevo craftsmen were sold at fairs in Saransk, Lada, Romodanovo, as well as in Spassk and Mokshan in Penza Region and Pochinki in Nizhny Novgorod

The first references about the Russian village Shishkeevo in the Republic of Mordovia date back to 1638. Until 1928, it was a part of the Insarsky District, Penza Province. Thanks to rich clay deposits of good quality, the village very soon became one of the pottery centers of the region, along with Bolshoi Kazarinov in Nizhny Novgorod Province, Sukhoi Karsun in Simbirsk Province, and Abashevo in Penza Province. “We are sitting on clay. Is it possible not to become a potter?” local craftsmen said.

Pottery was a seasonal craft in Shishkeevo. Most craftsmen worked in autumn, when farming was finished. Pottery was a family business. Children were taught to make pottery from the age of 8-10. Whole dynasties of craftsmen worked in the village. Shitikhins, Lazarevs, Lyautkins, Musyrkins were among them.

Women helped prepare clay, load the wares into the furnace, and grind pigments for the glaze. Clay used to be dug in late autumn. Then it was kneaded by feet and left to freeze. A necessary amount of clay was brought in the hut and put under the benches and on the shelves. As the clay thawed, it was mixed with water and kneaded by hands until clay turn into homogeneous mass.

Until 1918, Shishkeevo craftsmen used hand-spun pottery wheels. First of all, the walls of pots and dishes were made up with special coils, and then they were worked on with a wooden knife, while the wheel was rotated with one hand. In 1918, several families of potters from Samara Province came to the village and brought a new kick wheel technology. The earthenware was pulled on it from a single piece of clay.

The finished dishes had to be dried during 2-4 days, and then they were fired for 4-8 hours in Russian stoves at a temperature of 600-700 degrees, on the hearthstone that is the lower surface of the stove. Goods made by the Shishkeevo craftsmen were sold at fairs in Saransk, Lada, Romodanovo, as well as in Spassk and Mokshan in Penza Region and Pochinki in Nizhny Novgorod