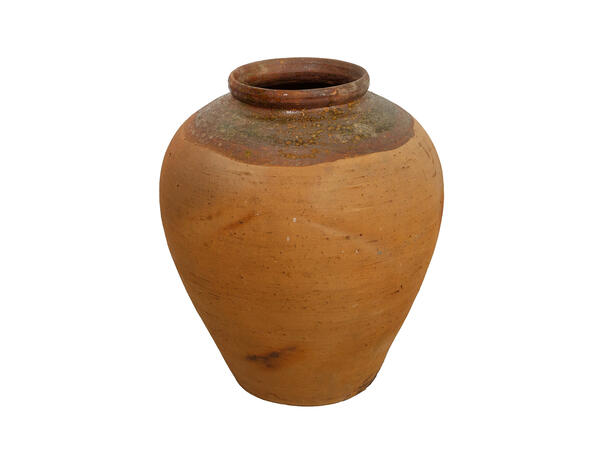

The earthenware pot (korchaga) for storing brew was given to the museum by the potter Kuzma Shitikhin from the village of Shishkeevo, Ruzaevsky District, Mordovian ASSR. He created it about 1946. He created it about 1946. The pot was used for storing kvass and oil.

The korchaga inside and outside by the neck are covered with greenish enamel —special composition that, when fired, turned into a glassy alloy, glaze.

All the dishes in Shishkeevo were made on a hand-spun potter’s wheel until 1918. Later, the craftsmen gradually began to master a foot-driven wheel — a “machine”. It rotated faster, so the walls of the pots came out thinner and neater. On such a wheel, the item was not gradually built up with coils of rolled clay, but as if it was pulled from a single piece. At the same time, the masters from Shishkeevo did not completely abandon the usual hand-spun wheel, since it was more convenient to make large dishes on it: it was easier to create massive walls with coils than to pull from a single piece.

People mined white, yellow and red clay near the village. Various impurities determined its color. The technique of making dishes depended on the type of clay and the amount of sand contained in it. Red, “low-sand” clay was considered the most plastic, “greasy”. It was used mainly for glazed dishes, ceramics covered with glaze.

On a hand-spun wheel, masters made gray crockery from clay with a large amount of impurities that make the material less greasy. The clay brought from the mining place was not used immediately, people dumped it in the yard and let it lie down for a year. Russian potters called this method “letovanie”. Under the influence of cold and heat, the clay changed its crystal structure, it “cleaned out”. The dirt contained in it, the roots of the plants, the remnants of grass rotted. The “matured” clay was split, chopped, stirred in water, sedimented, stones and debris were carefully removed. Then the water was drained, and the prepared material was covered with a cloth and put in the shade. The excess moisture gradually evaporated, the clay acquired the consistency of dough, from which it was already possible to sculpt dishes. It was laid out for storage in the huts where the masters worked and lived.

Ethnographer N. Runovsky, who studied the pottery craft, said:

The korchaga inside and outside by the neck are covered with greenish enamel —special composition that, when fired, turned into a glassy alloy, glaze.

All the dishes in Shishkeevo were made on a hand-spun potter’s wheel until 1918. Later, the craftsmen gradually began to master a foot-driven wheel — a “machine”. It rotated faster, so the walls of the pots came out thinner and neater. On such a wheel, the item was not gradually built up with coils of rolled clay, but as if it was pulled from a single piece. At the same time, the masters from Shishkeevo did not completely abandon the usual hand-spun wheel, since it was more convenient to make large dishes on it: it was easier to create massive walls with coils than to pull from a single piece.

People mined white, yellow and red clay near the village. Various impurities determined its color. The technique of making dishes depended on the type of clay and the amount of sand contained in it. Red, “low-sand” clay was considered the most plastic, “greasy”. It was used mainly for glazed dishes, ceramics covered with glaze.

On a hand-spun wheel, masters made gray crockery from clay with a large amount of impurities that make the material less greasy. The clay brought from the mining place was not used immediately, people dumped it in the yard and let it lie down for a year. Russian potters called this method “letovanie”. Under the influence of cold and heat, the clay changed its crystal structure, it “cleaned out”. The dirt contained in it, the roots of the plants, the remnants of grass rotted. The “matured” clay was split, chopped, stirred in water, sedimented, stones and debris were carefully removed. Then the water was drained, and the prepared material was covered with a cloth and put in the shade. The excess moisture gradually evaporated, the clay acquired the consistency of dough, from which it was already possible to sculpt dishes. It was laid out for storage in the huts where the masters worked and lived.

Ethnographer N. Runovsky, who studied the pottery craft, said: