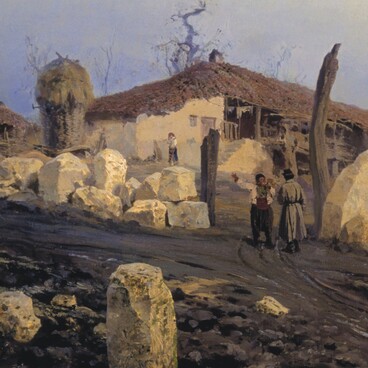

The exhibition contains a painting by the painter Leonid Solomatkin “Estate Manager”s Party”. The painter depicted a company of men: citizens, officials, clerks. There are framed lithographs and a wag-on-the-wall clock on the walls. On the right, you can see a set table with a samovar, bottles, and glasses; next to it, there is a plate with sushki (small, crunchy bread rings eaten for dessert, usually with tea). A floppy-eared dog peeps out from under the table. A violinist and a guitarist are playing in front of the audience, one of the characters is singing, and the other is dancing.

Solomatkin painted the ridiculous, bigheaded figures of the characters, whose gestures and facial expressions are exaggerated. However, the author’s position is kind; his intonation is distinguished by soft humor. At the same time, Solomatkin very accurately depicted the details of the furnishings and clothes: a plank floor, a simple teapot, the styles of frock coats, striped wallpaper that came off in places.

Leonid Solomatkin orphaned at an early age. He did not remember his parents. According to him, in his early childhood he endured ‘everything that falls to the poor orphan”s lot.’ Once Solomatkin learned that the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture accepts young people of all classes, he went from the Kursk governorate to Moscow.

He walked to Moscow on foot for several months. In order to earn money for food, the young painter took on any job. Solomatkin managed to enter the School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture. He was sheltered in a state apartment by Nikolai Ramazanov, the director of the school.

The teaching methods in Moscow could be characterized as liberating: students were not constrained by the strict requirements of the academic program, as in the St. Petersburg Academy of Fine Arts. However, in February 1861, Solomatkin submitted a transfer request to the Academy of Fine Arts, where he enrolled as a non-matriculated student.

Painter’s contemporaries remembered him as “kind, ingenuous to the point of naivety and so frank that it sometimes caused problems.” Solomatkin quickly became a favorite among teachers and comrades. Since the 1860s, he took part in academic exhibitions and received two silver medals for the paintings “Sexton”s Name Day” and “Policemen-Slavilshchiki” (also known as “The Glorifying Policemen” or “Christmas Chorus”).

The critic Vladimir Stasov praised Solomatkin’s work. His paintings were compared with the works of Nikolay Gogol and Fyodor Dostoevsky. Contemporaries noted the exact transmission of articulation and gestures, accuracy in the depiction of everyday details. Solomatkin always painted ‘alia prima’, that means from Italian ‘very quickly, without waiting for the previous paint layer to dry’.

However, already in the 1870s, the name of the master began to be mentioned less and less in the press, he stopped participating in exhibitions, and people began to forget about him. The publicist and artist Alexandre Benois in the History of Russian Painting in the 19th century’ wrote about Solomatkin as the author of one painting:

Solomatkin painted the ridiculous, bigheaded figures of the characters, whose gestures and facial expressions are exaggerated. However, the author’s position is kind; his intonation is distinguished by soft humor. At the same time, Solomatkin very accurately depicted the details of the furnishings and clothes: a plank floor, a simple teapot, the styles of frock coats, striped wallpaper that came off in places.

Leonid Solomatkin orphaned at an early age. He did not remember his parents. According to him, in his early childhood he endured ‘everything that falls to the poor orphan”s lot.’ Once Solomatkin learned that the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture accepts young people of all classes, he went from the Kursk governorate to Moscow.

He walked to Moscow on foot for several months. In order to earn money for food, the young painter took on any job. Solomatkin managed to enter the School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture. He was sheltered in a state apartment by Nikolai Ramazanov, the director of the school.

The teaching methods in Moscow could be characterized as liberating: students were not constrained by the strict requirements of the academic program, as in the St. Petersburg Academy of Fine Arts. However, in February 1861, Solomatkin submitted a transfer request to the Academy of Fine Arts, where he enrolled as a non-matriculated student.

Painter’s contemporaries remembered him as “kind, ingenuous to the point of naivety and so frank that it sometimes caused problems.” Solomatkin quickly became a favorite among teachers and comrades. Since the 1860s, he took part in academic exhibitions and received two silver medals for the paintings “Sexton”s Name Day” and “Policemen-Slavilshchiki” (also known as “The Glorifying Policemen” or “Christmas Chorus”).

The critic Vladimir Stasov praised Solomatkin’s work. His paintings were compared with the works of Nikolay Gogol and Fyodor Dostoevsky. Contemporaries noted the exact transmission of articulation and gestures, accuracy in the depiction of everyday details. Solomatkin always painted ‘alia prima’, that means from Italian ‘very quickly, without waiting for the previous paint layer to dry’.

However, already in the 1870s, the name of the master began to be mentioned less and less in the press, he stopped participating in exhibitions, and people began to forget about him. The publicist and artist Alexandre Benois in the History of Russian Painting in the 19th century’ wrote about Solomatkin as the author of one painting: