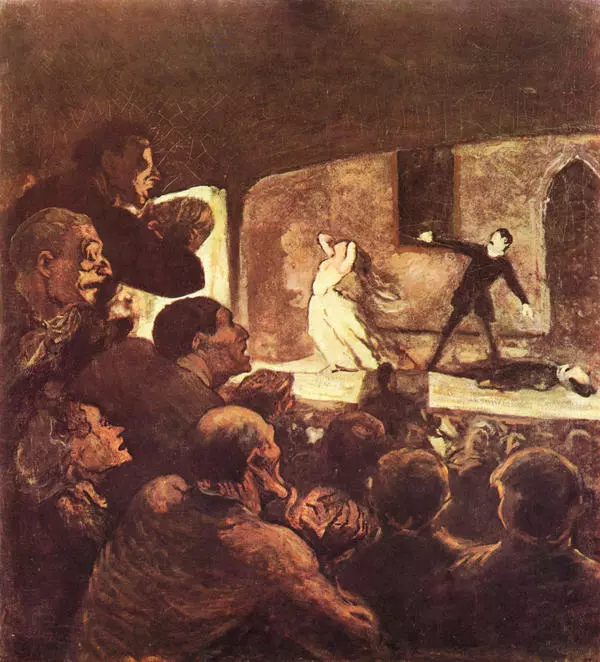

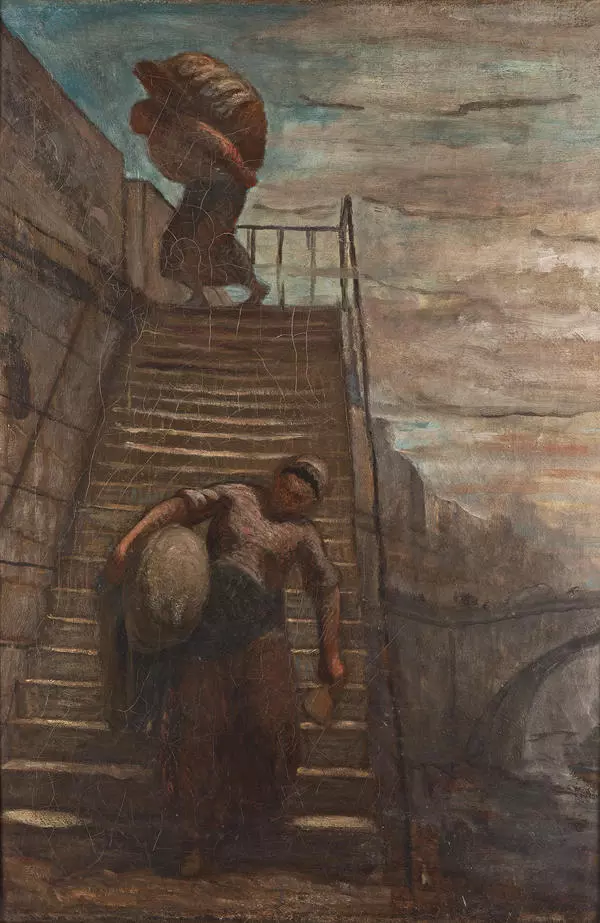

One of the two large-size facsimile (the most accurate) reproductions of paintings by the French artist Honoré /onorE/ Daumier /domjE/. The director bought them for his new apartment on PotYlikha Street in 1935. Both paintings are dedicated to the theater but could be a bridge to the cinema. Crispin and Scapin are the characters from A Comedy of Masks which he loved from his youth and which became the prototype of Eisenstein’s archetype films.

Daumier worked on this painting in 1858-1860, but it was only after his death that the painting was recognized as a masterpiece of art and exhibited in the Louvre. Today, it is on display at the Paris D’Orsay Museum.

The two characters in the painting are theatrical. Crispin /krispEn/ is a cunning, though clumsy servant from the play The Student of SalamAnca, or Noble Enemies (1654) by the French comedy dramatist Paul ScarrOn. Many other play writers took this character and made it a household name. He is always played in his distinctive costume — a black short caftan with large white collar, belt and lace cuffs. Scapin /skapEn/ is the character of Moliere’s comedy The Tricks of Scapin. The great French playwright based the character of Scapin — who he was the first to play at the Palais Royal Theater in 1671 — on the trickster Brighella from the Italian folk comedy.

The Italian commedia dell’arte, which Eisenstein loved from childhood, has permanent characters (masks) with a certain set of traits: the mischievous Harlequin, the charming Colombine, the fictitious scientist Bologna Doctor, the scrappy Captain and other embodiments of human traits and weaknesses. The mask of the simpleton Pedrolino transformed in the French theater into the image of Pierrot, sad and eternally in love. The audience always knows what social and psychological type the characters represent on stage. However, the actors always improvise, invent unexpected actions and jokes, make fun of current events, enter into communication with the audience and refresh the old known stories.

Back in his youth, while engaged in the theater, Sergei Eisenstein developed different takes on the themes of Italian folk comedy and its masks. When he came to the cinema, he used the same principles and traditions in the theory and practice of the archetype. It wasn’t just a “guy next door, ” non-professional role performer that Eisenstein called an archetype, but a person whose appearance can instantly reveal the character, belonging to a certain social or ethnic group. From Daumier”s paintings and graphics, he learned how to choose the expressive appearance of characters for his films. The double portrait of Crispin and Scapin is also an example of expressive light accents on faces. Eisenstein called them “light masks” and masterfully applied them in the movie Ivan the Terrible.

Daumier worked on this painting in 1858-1860, but it was only after his death that the painting was recognized as a masterpiece of art and exhibited in the Louvre. Today, it is on display at the Paris D’Orsay Museum.

The two characters in the painting are theatrical. Crispin /krispEn/ is a cunning, though clumsy servant from the play The Student of SalamAnca, or Noble Enemies (1654) by the French comedy dramatist Paul ScarrOn. Many other play writers took this character and made it a household name. He is always played in his distinctive costume — a black short caftan with large white collar, belt and lace cuffs. Scapin /skapEn/ is the character of Moliere’s comedy The Tricks of Scapin. The great French playwright based the character of Scapin — who he was the first to play at the Palais Royal Theater in 1671 — on the trickster Brighella from the Italian folk comedy.

The Italian commedia dell’arte, which Eisenstein loved from childhood, has permanent characters (masks) with a certain set of traits: the mischievous Harlequin, the charming Colombine, the fictitious scientist Bologna Doctor, the scrappy Captain and other embodiments of human traits and weaknesses. The mask of the simpleton Pedrolino transformed in the French theater into the image of Pierrot, sad and eternally in love. The audience always knows what social and psychological type the characters represent on stage. However, the actors always improvise, invent unexpected actions and jokes, make fun of current events, enter into communication with the audience and refresh the old known stories.

Back in his youth, while engaged in the theater, Sergei Eisenstein developed different takes on the themes of Italian folk comedy and its masks. When he came to the cinema, he used the same principles and traditions in the theory and practice of the archetype. It wasn’t just a “guy next door, ” non-professional role performer that Eisenstein called an archetype, but a person whose appearance can instantly reveal the character, belonging to a certain social or ethnic group. From Daumier”s paintings and graphics, he learned how to choose the expressive appearance of characters for his films. The double portrait of Crispin and Scapin is also an example of expressive light accents on faces. Eisenstein called them “light masks” and masterfully applied them in the movie Ivan the Terrible.