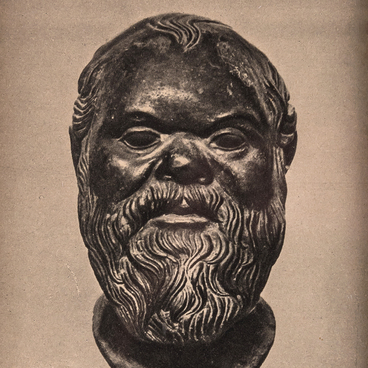

The director had this a photographic copy of one of the earliest portraits of the 16-th century Russian Tsar Ivan the Fourth (1530–1584) hung under the portrait of Toussaint LouvertUre on the bookshelf. Eisenstein obtained it while preparing to direct the movie Ivan the Terrible. He kept the painted portrait of the Tsar in his apartment as a memory of the unfinished and banned film: the second episode of Ivan the Terrible was prohibited; the footage of the third episode, partially filmed, was destroyed in 1951.

Eisenstein, though scrupulously studied the historical sources, was far from meticulous imitation of Ivan the Terrible. He primarily sought to create an expressive image of the autocrat: to show how unlimited power inevitably destroys the state and the sovereign. As the famous movie expert LeonId KozlOv put it, this film by Eisenstein is ‘not so much a story as a theory of autocratic power.’ In this sense, the movie went beyond the 15th century and beyond Russia.

In preparing for the film, Eisenstein drew hundreds of sketches for different scenes in which the image of Ivan the Terrible was changing. A teenager, frightened by the boyars (members of the highest rank of the feudal nobility, second only to the ruling princes from the 10th century to the 17th century), became a romantic young man who had himself crowned with the Monomakh’s Cap “for the sake of the great Russian kingdom” and finally freed Moscow from the Tatar-Mongol yoke. His suspicion, cruelty, and impunity change him dramatically. Some historians criticized the director for deviating from the facts known to science, but Eisenstein was convinced that art is not an illustration of a history textbook, but a way to emotionally relive and understand the meaning of historical processes and personalities through powerful images. Alexander Pushkin adhered to this exact principle in his tragedy Boris Godunov, where he figuratively embodied the inevitable mental anguish of the ruler responsible for all the blood, although perhaps in reality Tsar Boris was not guilty of the death of Tsarevich Dmitry. He also created a convincing image of Salieri as a sinful envious man, although the real-life composer did not actually poison Mozart. In his movie about Tsar Ivan, Sergei Eisenstein consciously followed Pushkin’s tradition.

When Eisenstein showed the photographic copy of Tsar Ivan’s painted portrait to Nikolai Cherkasov, he jestly teased the great actor: “You look nothing like him!” However, the product of their artistic union,

the tragic image of the first Russian autocrat forever joined the classics of world art.

Eisenstein, though scrupulously studied the historical sources, was far from meticulous imitation of Ivan the Terrible. He primarily sought to create an expressive image of the autocrat: to show how unlimited power inevitably destroys the state and the sovereign. As the famous movie expert LeonId KozlOv put it, this film by Eisenstein is ‘not so much a story as a theory of autocratic power.’ In this sense, the movie went beyond the 15th century and beyond Russia.

In preparing for the film, Eisenstein drew hundreds of sketches for different scenes in which the image of Ivan the Terrible was changing. A teenager, frightened by the boyars (members of the highest rank of the feudal nobility, second only to the ruling princes from the 10th century to the 17th century), became a romantic young man who had himself crowned with the Monomakh’s Cap “for the sake of the great Russian kingdom” and finally freed Moscow from the Tatar-Mongol yoke. His suspicion, cruelty, and impunity change him dramatically. Some historians criticized the director for deviating from the facts known to science, but Eisenstein was convinced that art is not an illustration of a history textbook, but a way to emotionally relive and understand the meaning of historical processes and personalities through powerful images. Alexander Pushkin adhered to this exact principle in his tragedy Boris Godunov, where he figuratively embodied the inevitable mental anguish of the ruler responsible for all the blood, although perhaps in reality Tsar Boris was not guilty of the death of Tsarevich Dmitry. He also created a convincing image of Salieri as a sinful envious man, although the real-life composer did not actually poison Mozart. In his movie about Tsar Ivan, Sergei Eisenstein consciously followed Pushkin’s tradition.

When Eisenstein showed the photographic copy of Tsar Ivan’s painted portrait to Nikolai Cherkasov, he jestly teased the great actor: “You look nothing like him!” However, the product of their artistic union,

the tragic image of the first Russian autocrat forever joined the classics of world art.