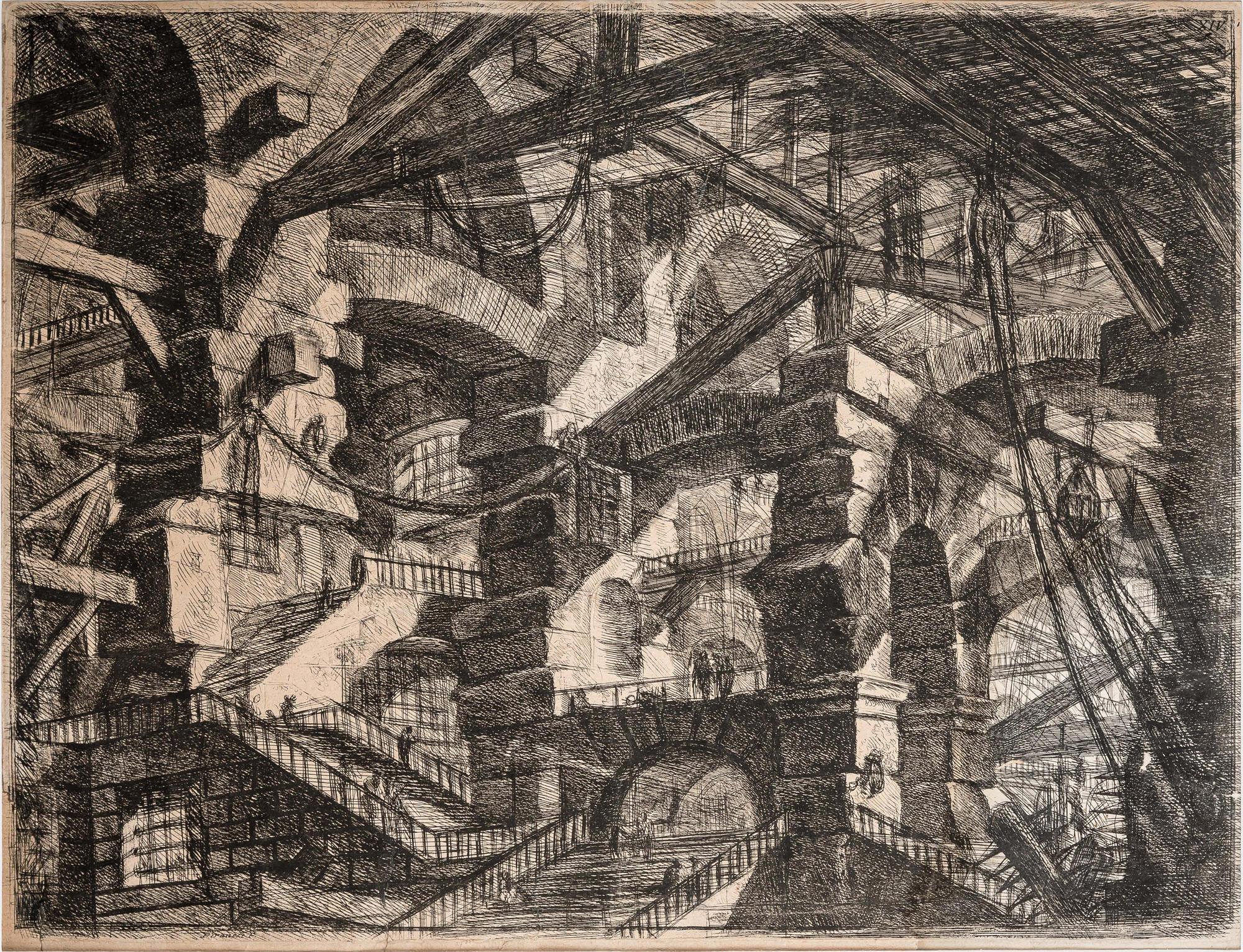

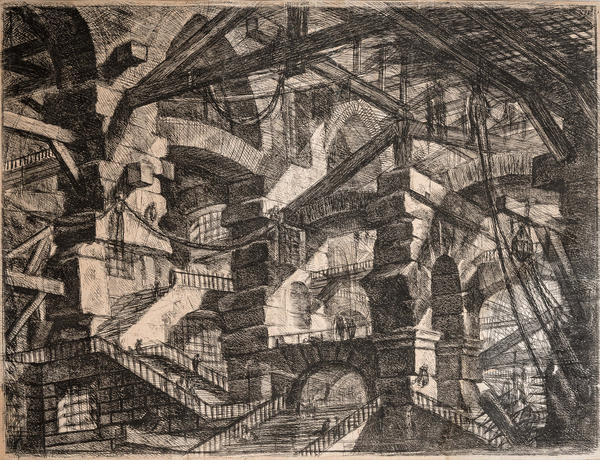

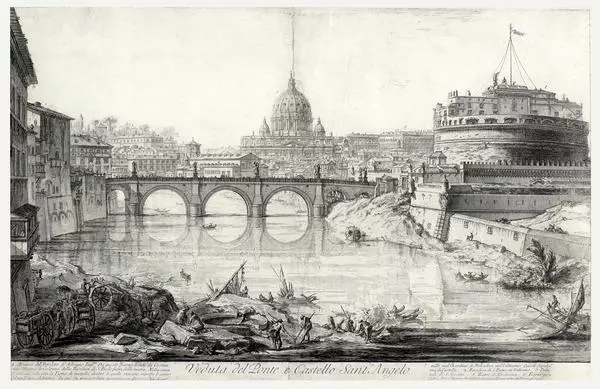

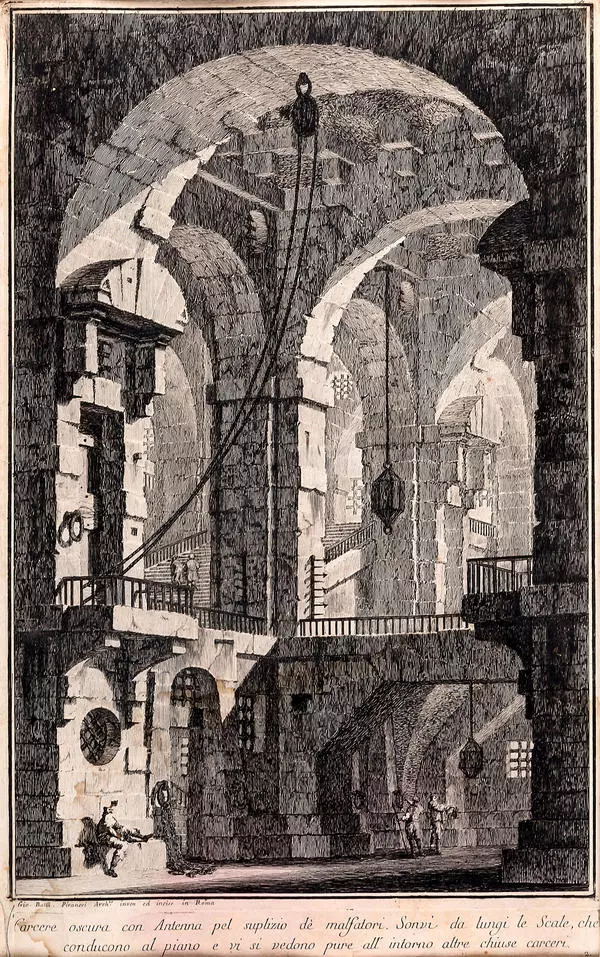

Italian archaeologist and artist GiovAnni BattIsta PiranEsi created his ‘Imaginary Prisons’ (‘Carceri d’Invenzione’) series in 1761. The series comprises 16 prints, and the fourteenth print ended up in Eisenstein’s apartment on PotYlikha Street.

In ‘Compassionate nature, ’ Eisenstein wrote that everything in that print ‘seemed to be demolished by a hurricane’, and that ‘in place of a modest and lyrically timid page of the early Prison, there is a great storm that pulls everything out of place: ropes, staircases leading in all directions, exploding arches, huge boulders toppling from one another…’ Every object within this print is bursting out of the static and transitioning to a new dynamic state. Eisenstein has describes it thusly in the chapter titled ‘Piranesi: the Fluidity of the Form’ of his work, ‘Pathos’:‘The nature of the architectural fantasies themselves, where one system of views flows into others; where certain plans unfold endlessly behind others and beckon the sight to follow them into the unknown; where staircases go up one cliff after another, ascending straight into heavens, or cascade down from there along the same cliffs. Some interpret the “Carceri” as the delusions of an archaeologist who took the stern romanticism and former glory of ruins of Rome a little too close to heart. Others see them as manifestations of persecution mania that plagued the artist at that stage of his life. Real reasons are listed for this occurrence, but many prefer the imaginary reasons to real ones. I think that over these few years Piranesi… has a flash of inspiration.’

In the grim Imaginary Prisons, with the hallways leading nowhere in particular, with overseers — or perhaps prisoners? — wandering through them; where light is swallowed by the darkness. These are not landscapes, and these are not architectural fantasies — these are the images of Italy during the tragic age of decline, wars, and fears. Shakespeare once said that the world is a stage. Piranesi is saying that the world is a prison. But his ecstatic art was the way to overcome the tragic nature of his time. Having analyzed Piranesi’s prints, Eisenstein derived a “Pathos formula” from them. He tested this formula against the works of writers, such as GOgol and Emile ZolA, and artists such as El GrEco and PicAsso. He himself used this formula to create the “IvAn GrOzny” cinematic tragedy.

In ‘Compassionate nature, ’ Eisenstein wrote that everything in that print ‘seemed to be demolished by a hurricane’, and that ‘in place of a modest and lyrically timid page of the early Prison, there is a great storm that pulls everything out of place: ropes, staircases leading in all directions, exploding arches, huge boulders toppling from one another…’ Every object within this print is bursting out of the static and transitioning to a new dynamic state. Eisenstein has describes it thusly in the chapter titled ‘Piranesi: the Fluidity of the Form’ of his work, ‘Pathos’:‘The nature of the architectural fantasies themselves, where one system of views flows into others; where certain plans unfold endlessly behind others and beckon the sight to follow them into the unknown; where staircases go up one cliff after another, ascending straight into heavens, or cascade down from there along the same cliffs. Some interpret the “Carceri” as the delusions of an archaeologist who took the stern romanticism and former glory of ruins of Rome a little too close to heart. Others see them as manifestations of persecution mania that plagued the artist at that stage of his life. Real reasons are listed for this occurrence, but many prefer the imaginary reasons to real ones. I think that over these few years Piranesi… has a flash of inspiration.’

In the grim Imaginary Prisons, with the hallways leading nowhere in particular, with overseers — or perhaps prisoners? — wandering through them; where light is swallowed by the darkness. These are not landscapes, and these are not architectural fantasies — these are the images of Italy during the tragic age of decline, wars, and fears. Shakespeare once said that the world is a stage. Piranesi is saying that the world is a prison. But his ecstatic art was the way to overcome the tragic nature of his time. Having analyzed Piranesi’s prints, Eisenstein derived a “Pathos formula” from them. He tested this formula against the works of writers, such as GOgol and Emile ZolA, and artists such as El GrEco and PicAsso. He himself used this formula to create the “IvAn GrOzny” cinematic tragedy.