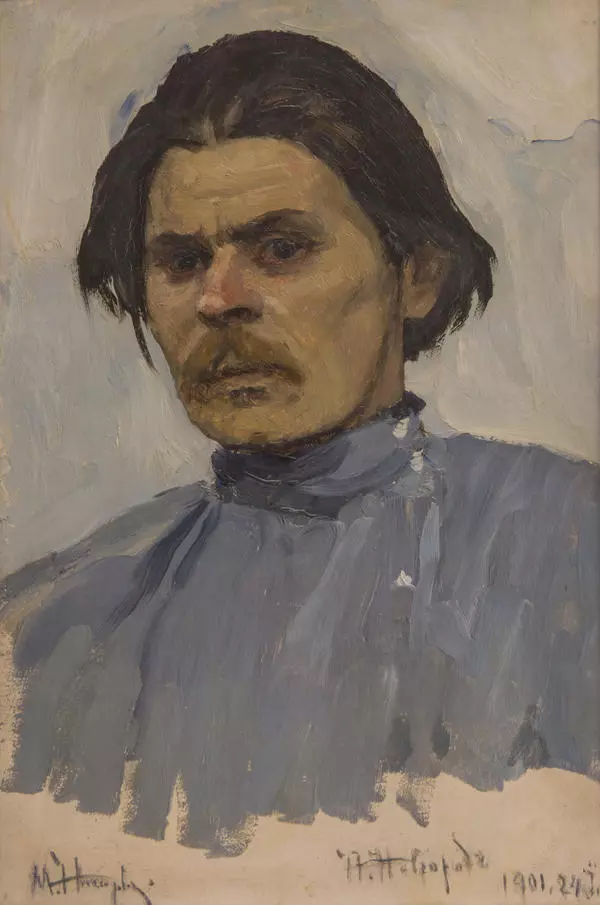

In 1877, Mikhail Vasilyevich Nesterov entered the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture, where he matured as an artist. Then Nesterov studied at the St. Petersburg Academy of Arts, several other art schools, and at the same time he worked hard and participated in numerous exhibitions that made him famous in the Russian artistic circles.

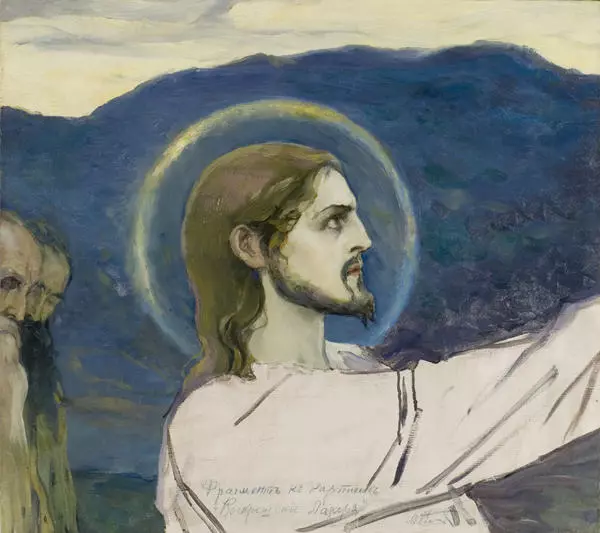

But the true glory came to the artist with the painting Vision to the Youth Bartholomew, created on an episode from the life of Reverend Sergius of Radonezh, which he himself considered the pinnacle of his work. That painting became not only one of the most outstanding works of the master, but also played a significant role in his life. Professor Prakhov, who at that time was in charge of painting of Vladimir Cathedral in Kiev, saw The Youth Bartholomew. The painting struck him so much with its depth and significance that the professor immediately invited Nesterov to paint the cathedral.

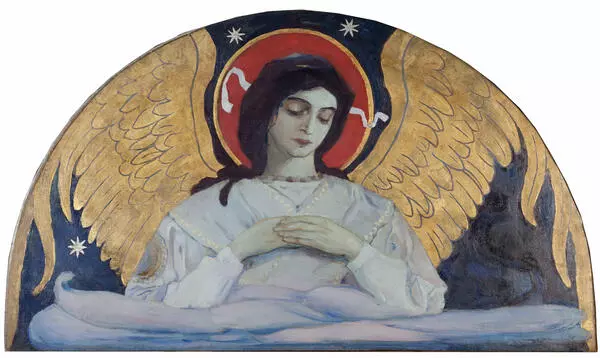

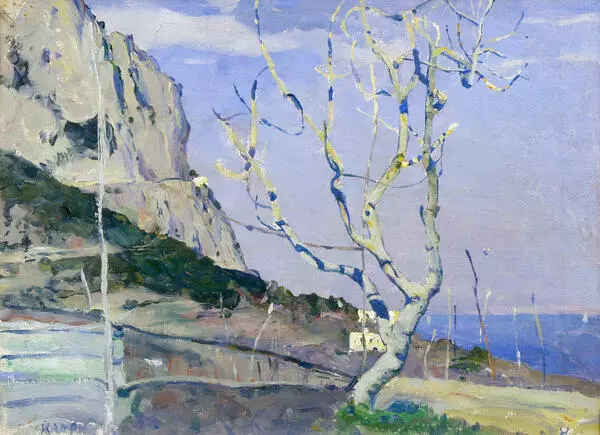

That was followed by work in other temples, including the palace church of Alexander Nevsky in Abastumani in Georgia, where Nesterov worked on the frescoes at the invitation of George, the younger brother of Emperor Nicholas II.

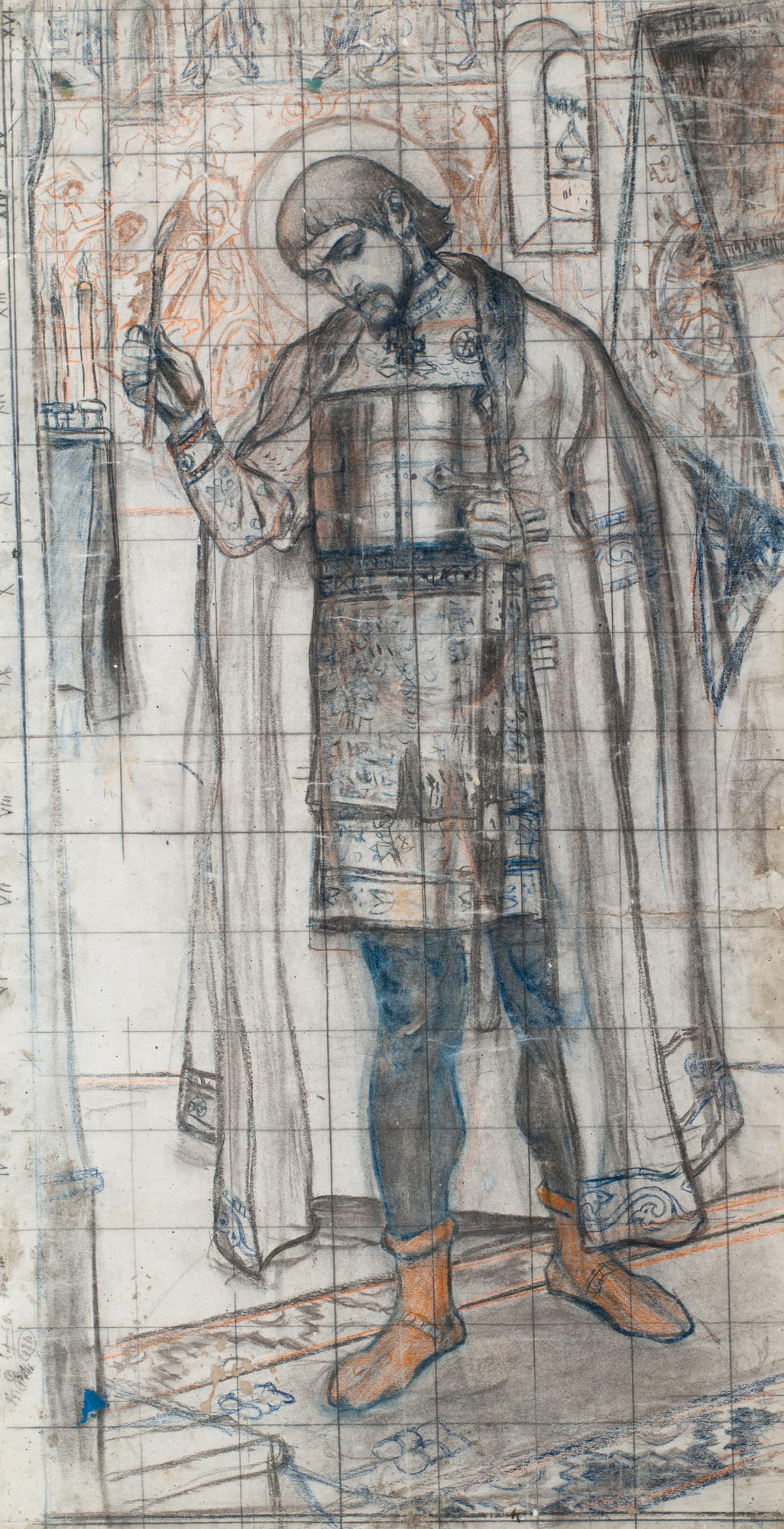

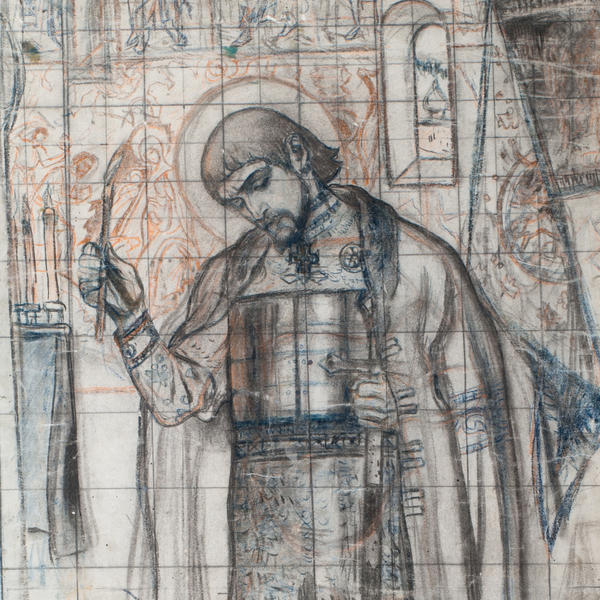

The work took five years and lasted from 1899 to 1904. That period is represented in the museum’s collection with a number of sketches, a special place among which belonging to the sketch Alexander Nevsky, which Mikhail Nesterov made in Abastumani. The drawing is made with colored pencils and differs significantly from the final image of Alexander on the wall of the church. Visitors of the temple see the prince facing half-turned to the right, making the sign of the cross and touching a large cross on his chest with his fingers, while in the sketch the figure of the saint is turned to the left, he holds a candle in his right hand in front of an icon, and a sword with his tightly clenched left hand.

But it is unlikely that the image corresponds to reality. First, Alexander accepted Christianity only shortly before his death, and second, he was not left-handed, so he held the sword with his right hand. Despite these obvious inaccuracies, the artist masterfully conveyed the spiritual beauty of one of the most revered Orthodox saints in Russia, his purity, and the inner drama inherent to Alexander’s personality.

The prince is drawn not in the common iconographic manner, but as a living person, though the sketch itself, and the corresponding fresco in the church are made in accordance with church canons. It is no coincidence that the image of Alexander, as well the other, the most famous, painting by Nesterov, Vision to the Youth Bartholomew, received and continue to receive a mixed reaction on the part of some churchmen.

But the true glory came to the artist with the painting Vision to the Youth Bartholomew, created on an episode from the life of Reverend Sergius of Radonezh, which he himself considered the pinnacle of his work. That painting became not only one of the most outstanding works of the master, but also played a significant role in his life. Professor Prakhov, who at that time was in charge of painting of Vladimir Cathedral in Kiev, saw The Youth Bartholomew. The painting struck him so much with its depth and significance that the professor immediately invited Nesterov to paint the cathedral.

That was followed by work in other temples, including the palace church of Alexander Nevsky in Abastumani in Georgia, where Nesterov worked on the frescoes at the invitation of George, the younger brother of Emperor Nicholas II.

The work took five years and lasted from 1899 to 1904. That period is represented in the museum’s collection with a number of sketches, a special place among which belonging to the sketch Alexander Nevsky, which Mikhail Nesterov made in Abastumani. The drawing is made with colored pencils and differs significantly from the final image of Alexander on the wall of the church. Visitors of the temple see the prince facing half-turned to the right, making the sign of the cross and touching a large cross on his chest with his fingers, while in the sketch the figure of the saint is turned to the left, he holds a candle in his right hand in front of an icon, and a sword with his tightly clenched left hand.

But it is unlikely that the image corresponds to reality. First, Alexander accepted Christianity only shortly before his death, and second, he was not left-handed, so he held the sword with his right hand. Despite these obvious inaccuracies, the artist masterfully conveyed the spiritual beauty of one of the most revered Orthodox saints in Russia, his purity, and the inner drama inherent to Alexander’s personality.

The prince is drawn not in the common iconographic manner, but as a living person, though the sketch itself, and the corresponding fresco in the church are made in accordance with church canons. It is no coincidence that the image of Alexander, as well the other, the most famous, painting by Nesterov, Vision to the Youth Bartholomew, received and continue to receive a mixed reaction on the part of some churchmen.