Andrey Nikolaevich Makarov (1923–1987) was born in Prague, where his parents were on a business trip. In 1941, after finishing high school, he volunteered for the front. He was wounded four times and demobilized due to disability in 1945. He was awarded the Orders of the Red Star and Glory, 3rd class, as well as other medals.

In 1946, Andrey Makarov began studying at an art studio for disabled war veterans in Moscow. However, already in 1947, he managed to enter the Surikov Moscow State Art Institute. In 1954, he took part in an exhibition of young artists.

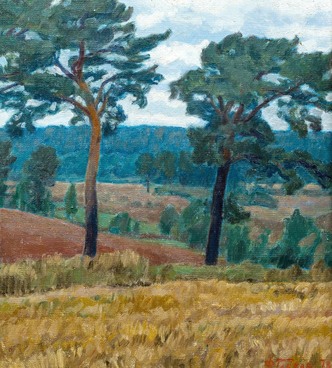

In the 1960s, landscape became Andrey Makarov’s favorite genre. He painted mainly the Russian North, where he regularly traveled to find inspiration. The antithesis of the north was Suzdal, the views of which were much warmer.

In the 1970s and 1980s, Makarov worked a lot in other regions — near Tver and Yaroslavl. At the same time, he always retained interest in the changing states of nature, depicting a bright motif on a faded background and comprehending the formula and meaning of the Russian landscape.

In terms of his artistic principles, Andrey Makarov followed the traditions of the Moscow school of painting, which is characterized by a love of modest, unassuming subjects. Moscow painting, ever since the 19th-century landscapists and painters of the association “Union of Russian Artists”, has been distinguished by a profound psychological approach not only in the transmission of states of nature, but also in the expressions of human feelings.

Makarov’s communication of innermost feelings acquired social power. As other landscape artists of his generation who went through the Great Patriotic War in their youth, he understood the price of life.

In 1984, the landscape

“Green May” was displayed at the Moscow spring exhibition. The artist loved

painting this particular month. In this work, he managed to depict the dim,

modest beauty of a day in May. Everything in Andrey Makarov’s canvas has fused

into a single image, where human presence is invisible. The outskirts, the

shed, the fence — everything speaks of the usual, measured life of people.