Maria Nikolaevna Volkonskaya (born Raevskaya), was born in 1806. She was married to Sergey Grigoryevich Volkonsky (1788-1865).

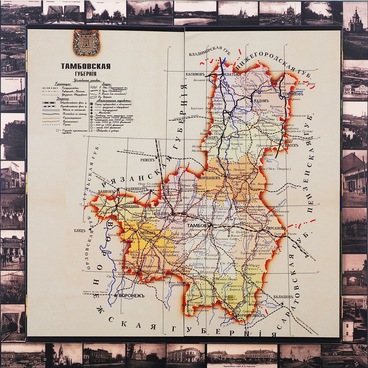

Sergey Volkonsky came from a princely family, he got a great education. The prince participated in the Patriotic War in 1812. For his distinguished service he was promoted to the rank of Mayor General. However, in the course of time the prince got disappointed in the existing political system and joined the ranks of the Decembrists in 1819. The arrest for the anti-state activity followed in 1826. He was sentenced to penal servitude for twenty years in Siberia.

In this hard period for the Volkonsky family Maria Nikolaevna made a decision to follow her husband to Siberia. These were hard and long years both for Sergey Volkonsky and his wife. During the servitude they lost their son, then their daughter, only two of their children managed to survive.

Amnesty, which followed the emperor’s Alexander II enthronement, bettered the married couple’s lot and let them return back home.

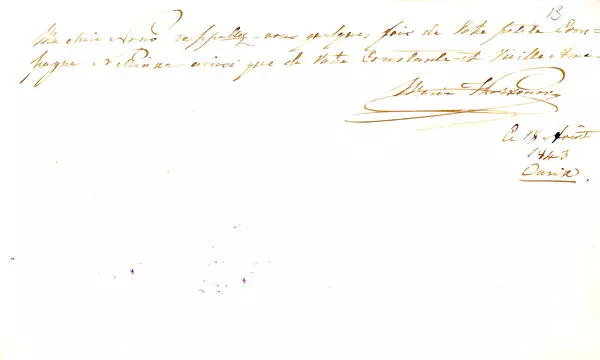

Maria Nikolaevna passed away in 1863 and left her family the notes she was making from 1825 till 1855 in French.

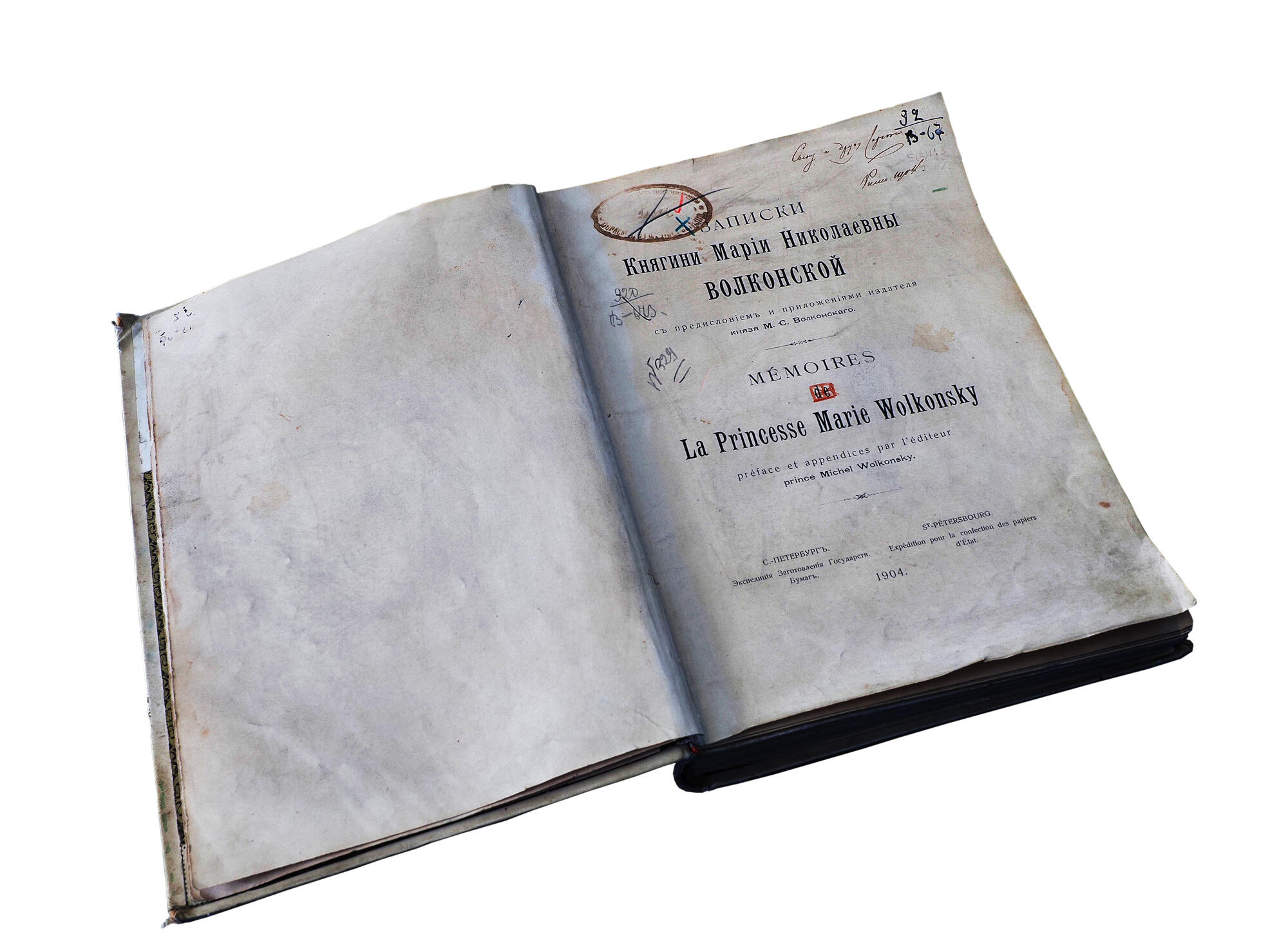

This edition of a book entitled The Notes of Princess Maria Nikolaevna Volkonskaya was issued in 1904 in Saint Petersburg, and for a long time it was kept in the home library of the Volkonsky family, in their estate in Pavlovka. On the front page there’s a dedicatory inscription “To my son and my friend. Rome. 1904” from prince Mikhail Sergeevich Volkonsky. The edition contains many illustrations, reproductions of paintings, engravings and drawings.

In her notes Maria Nikolaevna described the events of her life, lives of the Decembrists and their wives. Here’s what she wrote about the moment when she found out about the penal servitude: ‘My husband lost his title, finance, and civil rights, and was sentenced to penal servitude for twenty years and banishment for life. On July 26 he was sent to Siberia with prince Trubetskoy and prince Obolensky, Davydov, Artamon Murav’ev, Borisov brothers, and Yakubovich. When I found out about it from my brother, I declared to him that I’d follow my husband.’ How emblematic is her bravery and love to Sergey Grigoryevich and how strong was her determination despite the difficulties of being around him.

The book was very popular among the readers, as they could read an autobiographical story told by a fragile woman. The Notes isn’t just a book, but an artifact, an evidence of a tragic, but interesting period in the history of the Russian Empire.