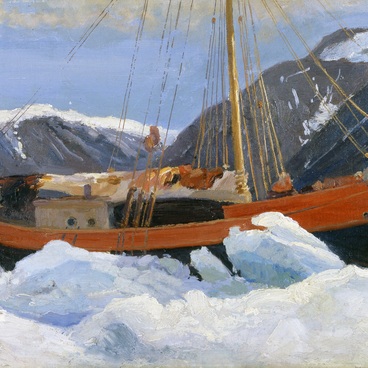

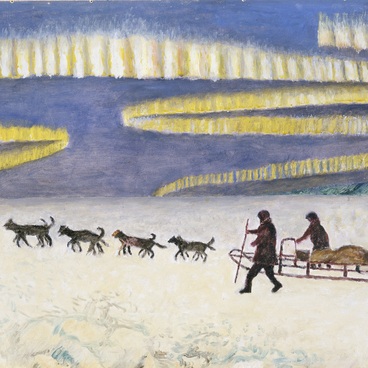

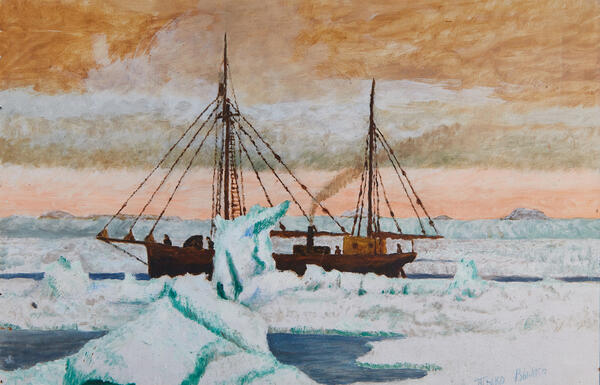

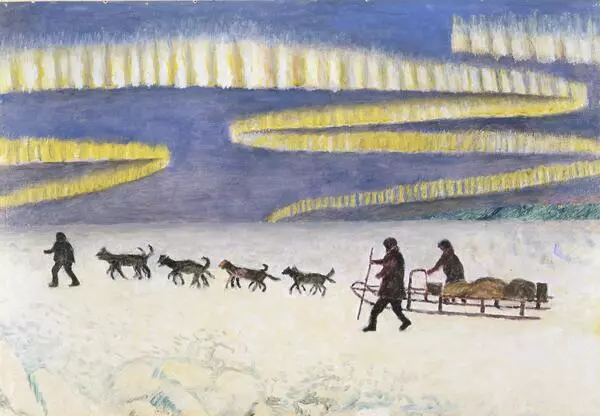

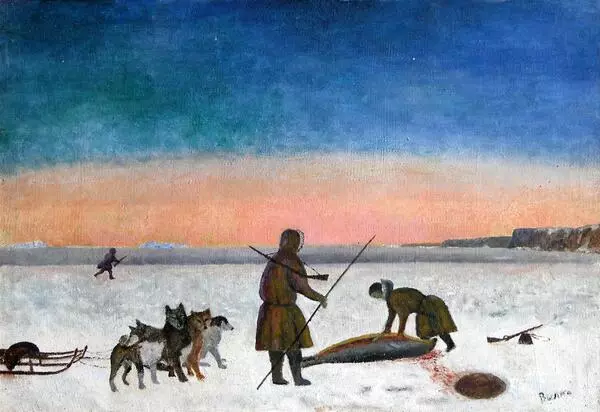

The decisive event in Tyko Vylka’s life was meeting Vladimir Rusanov (1875-1913), a Russian Arctic explorer, and joining his expeditions as a guide. Not only Rusanov noticed and appreciated Vylka’s talent, but also promoted his art so that it could be shown to the public.

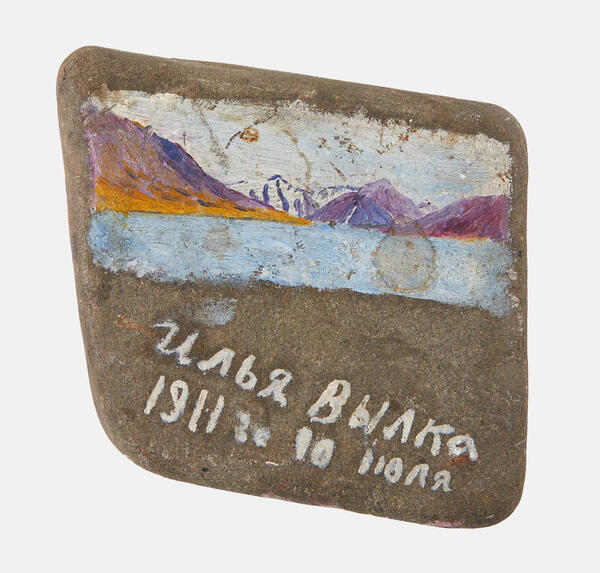

In 1910, an exhibition with the title ‘Russian North’ was organized in Arkhangelsk. Almost immediately, it caught the public eye. Among other pictures, a few landscapes by Vylka were exhibited. The best of them were sent as a gift to the Russian emperor Nicolas II and were later moved to the State Russian Museum.

Rusanov thought that Vylka needed training, and so he took the young Nenets to Moscow. He was taught by two masterful artists, Abram Arkhipov and Vasily Pereplyotchikov, who instructed him in basic artistic skills.

However, those classes took little effect on the Vylka’s unique and peculiar style. Arkhipov and Pereplyotchikov taught him about the tonality, showed him how to mix colours, how to render the volume of objects using light and shadows. But when the young Nenets tried repeating what he was taught, he failed again and again.

His mentors and teachers strived to make his work “better”, thinking that the striking uniqueness of Vylka’s paintings was due to lack of skill. Had they been able to eliminate the ‘flaws’ of his style, there would have been nothing left of the merits, of the exceptional integrity that Vylka’s professors could only dream of.

When painting his friend Rusanov, Vylka had to look at his photos: it was much more difficult to paint a portrait than a landscape. As for the latter, he was a very skillful landscape painter, able to render all the minor tones by memory. Vylka never forgot about his deceased friend.

As an old man, he used to tell stories about Rusanov: “He was a hospitable, cheerful man. This is how we lived: we had one heart and two heads. I spent my days with Rusanov with great pleasure. I taught him how to hunt. Sometimes, in the North of Novaya Zemlya, we were on the verge of death. Sometimes, we saw icebergs. We were the heroes of the Arctic. We have opened all the paths. We have shown the way. We were not afraid of dangers. We loved what we did.”

In 1910, an exhibition with the title ‘Russian North’ was organized in Arkhangelsk. Almost immediately, it caught the public eye. Among other pictures, a few landscapes by Vylka were exhibited. The best of them were sent as a gift to the Russian emperor Nicolas II and were later moved to the State Russian Museum.

Rusanov thought that Vylka needed training, and so he took the young Nenets to Moscow. He was taught by two masterful artists, Abram Arkhipov and Vasily Pereplyotchikov, who instructed him in basic artistic skills.

However, those classes took little effect on the Vylka’s unique and peculiar style. Arkhipov and Pereplyotchikov taught him about the tonality, showed him how to mix colours, how to render the volume of objects using light and shadows. But when the young Nenets tried repeating what he was taught, he failed again and again.

His mentors and teachers strived to make his work “better”, thinking that the striking uniqueness of Vylka’s paintings was due to lack of skill. Had they been able to eliminate the ‘flaws’ of his style, there would have been nothing left of the merits, of the exceptional integrity that Vylka’s professors could only dream of.

When painting his friend Rusanov, Vylka had to look at his photos: it was much more difficult to paint a portrait than a landscape. As for the latter, he was a very skillful landscape painter, able to render all the minor tones by memory. Vylka never forgot about his deceased friend.

As an old man, he used to tell stories about Rusanov: “He was a hospitable, cheerful man. This is how we lived: we had one heart and two heads. I spent my days with Rusanov with great pleasure. I taught him how to hunt. Sometimes, in the North of Novaya Zemlya, we were on the verge of death. Sometimes, we saw icebergs. We were the heroes of the Arctic. We have opened all the paths. We have shown the way. We were not afraid of dangers. We loved what we did.”