A renowned animalist and graphic artist, Alexey Komarov created the painting ‘Driving the Cattle to the Rear’. He was born on October 14, 1879, in the village of Skorodnoe, Tula governorate, in a family of merchants.

In 1898, Komarov entered the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture, where he studied for only two years, and enrolled in the class of a painter Nikolay Kasatkin. Later, he attended an art studio of Alexey Stepanov, a master of animal painting.

Since 1900, Komarov worked for the publishing houses of Alexei Stupin, Joseph Knebel, and others. He cooperated with state, pedagogical and children’s publishing houses and illustrated magazines, such as “Hound and Gun Hunting”, “the Hunter”s Herald”, “Family of Hunters”, and others.

After the October Revolution of 1917, the artist created illustrations for children’s books and magazines ‘Svetlyachok’ and ‘Murzilka’ and in the 1930s — book designs for the Ivan Sytin publishing house. During the Great Patriotic War, Komarov created posters in support of children’s health.

Komarov lived in the Kolomna District, where his art studio was, for more than 40 years. He painted not only classical landscapes, but also agricultural sketches.

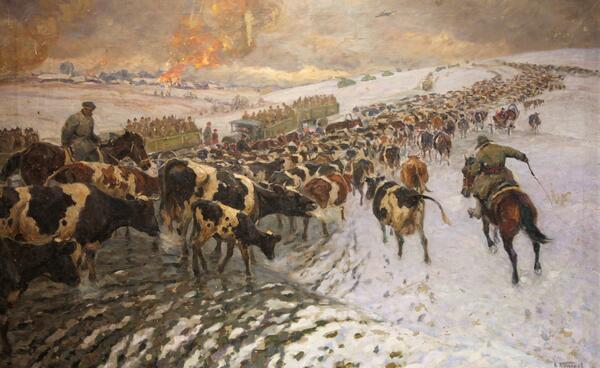

The painting “Driving the Cattle to the Rear” illustrates the difficult evacuation of animals to safe areas of 1941. Cows, horses, and pigs were of great value: some provided food for the population, while others were used to transport goods. There were not enough echelons (trains) even for people, so the cattle were driven right under the bombs, falling from German planes. German pilots often deliberately descended to fly lower and turn on their sirens. The frightened cows scattered, fell into pits and got injured; their milk was lost. Many calves, in particular, were killed.

The herds had to be watered, fed and guarded during stops, and the strays had to be picked up. The losses were enormous. Even when the herders reached safe areas, they had to find something to feed the herds: they did not have any supplies.

The animals were also moved so that the Germans would not get them. On the way to the East, the herders gave their horses over to the army. During the evacuation, some of the livestock was sold for meat. Herds were relocated to the Stavropol Krai, the Republic of Dagestan, the Stalingrad Oblast, and the Northern Caucasus. But it was an impossible task to transfer all the cattle from the occupied zones to the eastern districts. As a result, the Germans got 7 million horses, 17 million cows and bulls, 20 million pigs, as well as 27 million goats and sheep and 110 million poultry. Some of these animals were killed, and some were taken to Germany.

In 1898, Komarov entered the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture, where he studied for only two years, and enrolled in the class of a painter Nikolay Kasatkin. Later, he attended an art studio of Alexey Stepanov, a master of animal painting.

Since 1900, Komarov worked for the publishing houses of Alexei Stupin, Joseph Knebel, and others. He cooperated with state, pedagogical and children’s publishing houses and illustrated magazines, such as “Hound and Gun Hunting”, “the Hunter”s Herald”, “Family of Hunters”, and others.

After the October Revolution of 1917, the artist created illustrations for children’s books and magazines ‘Svetlyachok’ and ‘Murzilka’ and in the 1930s — book designs for the Ivan Sytin publishing house. During the Great Patriotic War, Komarov created posters in support of children’s health.

Komarov lived in the Kolomna District, where his art studio was, for more than 40 years. He painted not only classical landscapes, but also agricultural sketches.

The painting “Driving the Cattle to the Rear” illustrates the difficult evacuation of animals to safe areas of 1941. Cows, horses, and pigs were of great value: some provided food for the population, while others were used to transport goods. There were not enough echelons (trains) even for people, so the cattle were driven right under the bombs, falling from German planes. German pilots often deliberately descended to fly lower and turn on their sirens. The frightened cows scattered, fell into pits and got injured; their milk was lost. Many calves, in particular, were killed.

The herds had to be watered, fed and guarded during stops, and the strays had to be picked up. The losses were enormous. Even when the herders reached safe areas, they had to find something to feed the herds: they did not have any supplies.

The animals were also moved so that the Germans would not get them. On the way to the East, the herders gave their horses over to the army. During the evacuation, some of the livestock was sold for meat. Herds were relocated to the Stavropol Krai, the Republic of Dagestan, the Stalingrad Oblast, and the Northern Caucasus. But it was an impossible task to transfer all the cattle from the occupied zones to the eastern districts. As a result, the Germans got 7 million horses, 17 million cows and bulls, 20 million pigs, as well as 27 million goats and sheep and 110 million poultry. Some of these animals were killed, and some were taken to Germany.