In the second half of the 19th century, needlework was considered an important part of the upbringing and education of girls. Usually, women were taught crafts from the age of three. Bead embroidery and knitting all kinds of handbags, cases, boxes, and decorative panels was a favorite pastime of young noblewomen. All those things were created in a cozy atmosphere and then given as gifts to show affection.

Needlework was common within a family circle and during social events. Many ladies brought their needlework even to soirees.

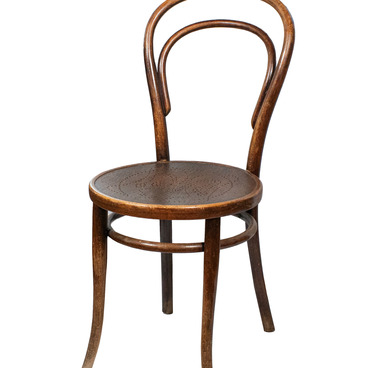

Such an interest in embroidery greatly influenced the appearance of needlework tables. There was even a tacit competition among the ladies for the best table. The tables came in a variety of shapes and designs. They were considered an exquisite piece of furniture for a noble house, they were used to adorn a drawing-room, a lady’s sanctum or a study, and since they were light and portable, they could be rearranged in different rooms: during the day they stood closer to a window, and in the evening, they were moved to a sofa.

Various compartments were used to store all the necessary needlework items — embroidery threads, needles, marbles, beads, scissors, and fabrics. A frame was pulled out from below to stretch the fabric on.

The museum houses an Oriental needlework table with Japanese motifs, performed in a complex technique of lacquer painting with shell inlay.

Lacquer art is one of the national treasures of Japan. Experts and collectors consider the Japanese lacquer technique to be “of the finest taste and the most exquisite applied art of the world”. The main features of the lacquer painting technique — shell inlay and volume carving — were borrowed from China. From the mid-6th century, due to the spread of Buddhism, the demand for lacquered altars and other ritual objects increased, therefore the lacquer technique was in demand in the areas where temples were built. When lacquer began to be used to decorate large surfaces, the technique became simpler. The stage of detailed preparatory draftsmanship was now skipped, and drawings were now freely applied to the varnish base.

Needlework was common within a family circle and during social events. Many ladies brought their needlework even to soirees.

Such an interest in embroidery greatly influenced the appearance of needlework tables. There was even a tacit competition among the ladies for the best table. The tables came in a variety of shapes and designs. They were considered an exquisite piece of furniture for a noble house, they were used to adorn a drawing-room, a lady’s sanctum or a study, and since they were light and portable, they could be rearranged in different rooms: during the day they stood closer to a window, and in the evening, they were moved to a sofa.

Various compartments were used to store all the necessary needlework items — embroidery threads, needles, marbles, beads, scissors, and fabrics. A frame was pulled out from below to stretch the fabric on.

The museum houses an Oriental needlework table with Japanese motifs, performed in a complex technique of lacquer painting with shell inlay.

Lacquer art is one of the national treasures of Japan. Experts and collectors consider the Japanese lacquer technique to be “of the finest taste and the most exquisite applied art of the world”. The main features of the lacquer painting technique — shell inlay and volume carving — were borrowed from China. From the mid-6th century, due to the spread of Buddhism, the demand for lacquered altars and other ritual objects increased, therefore the lacquer technique was in demand in the areas where temples were built. When lacquer began to be used to decorate large surfaces, the technique became simpler. The stage of detailed preparatory draftsmanship was now skipped, and drawings were now freely applied to the varnish base.