This sundial is part of the settings of the memorial obelisk installed in the center of the cathedral square of the Trinity Lavra of St. Sergius in 1792. At that time, four oval copper plaques with texts stamped on them were fixed on the pedestal from four sides. The texts were dedicated to the merits of the monastery of St. Sergius to the Fatherland in the “unfortunate times for Russia.” The medallions referred to the contribution of the monastery to the cause of liberation from the Poles in the Time of Troubles, the help provided by the Lavra to overcome the Streltsy rebellions of the late 17th century, the St. Sergius’s blessing of princes led by Dmitry Donskoy on the Kulikovo Battle for the fateful battle for Rus and other important events.

The sundial was attached to the three sides of the obelisk, by which it was possible to determine not only the time, but also the month. The idea of the sun-dial, as well as the obelisk itself, belonged to the church hierarch — Metropolitan of Moscow Platon (Levshin), Father Superior of the Trinity Lavra of St. Sergius in 1737-1812.

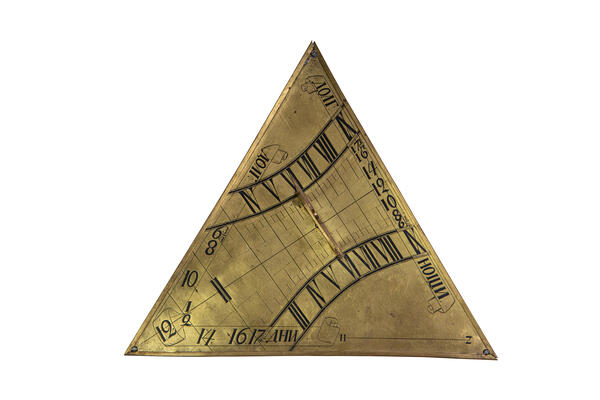

The mechanical clocks on the bell tower, which measured the time, were checked against the sundials. The clock was a triangular-shaped copper plate with “gilded through the fire pointers” — gnomons. The only facet that did not have a clock was the northern one, since it was not illuminated by the sun. However, it also allowed the installation of an additional board with a dial “for pleasant symmetry.”

The Lavra’s sundial is one of the variants of a vertical sundial oriented to the cardinal directions. They allowed not only to determine the time of day, by the hour, half-hour and fifteen-minute divisions, but also the duration of the day and night at any time of the year. The author of such a finely calculated mechanism is not known with absolute certainty. However, some sources mention the name of Mikhail Pankevich (1757-1812), a teacher of mathematics and astronomy at the Moscow University. He had a reputation in Moscow as a “knowledgeable mechanic and engineer.” His works included the sundial of the Moscow Donskoy Monastery.

In the thirties of the 20th century, the copper oval boards and the ball on the obelisk disappeared, and the sundial was transferred to the museum. After the Great Patriotic War, during the overall restoration of the Lavra, copies of the lost oval boards were made, and a new copper ball was installed at the top of it. In 2000, a new sundial was made — an exact copy of the previous ones.

The sundial was attached to the three sides of the obelisk, by which it was possible to determine not only the time, but also the month. The idea of the sun-dial, as well as the obelisk itself, belonged to the church hierarch — Metropolitan of Moscow Platon (Levshin), Father Superior of the Trinity Lavra of St. Sergius in 1737-1812.

The mechanical clocks on the bell tower, which measured the time, were checked against the sundials. The clock was a triangular-shaped copper plate with “gilded through the fire pointers” — gnomons. The only facet that did not have a clock was the northern one, since it was not illuminated by the sun. However, it also allowed the installation of an additional board with a dial “for pleasant symmetry.”

The Lavra’s sundial is one of the variants of a vertical sundial oriented to the cardinal directions. They allowed not only to determine the time of day, by the hour, half-hour and fifteen-minute divisions, but also the duration of the day and night at any time of the year. The author of such a finely calculated mechanism is not known with absolute certainty. However, some sources mention the name of Mikhail Pankevich (1757-1812), a teacher of mathematics and astronomy at the Moscow University. He had a reputation in Moscow as a “knowledgeable mechanic and engineer.” His works included the sundial of the Moscow Donskoy Monastery.

In the thirties of the 20th century, the copper oval boards and the ball on the obelisk disappeared, and the sundial was transferred to the museum. After the Great Patriotic War, during the overall restoration of the Lavra, copies of the lost oval boards were made, and a new copper ball was installed at the top of it. In 2000, a new sundial was made — an exact copy of the previous ones.