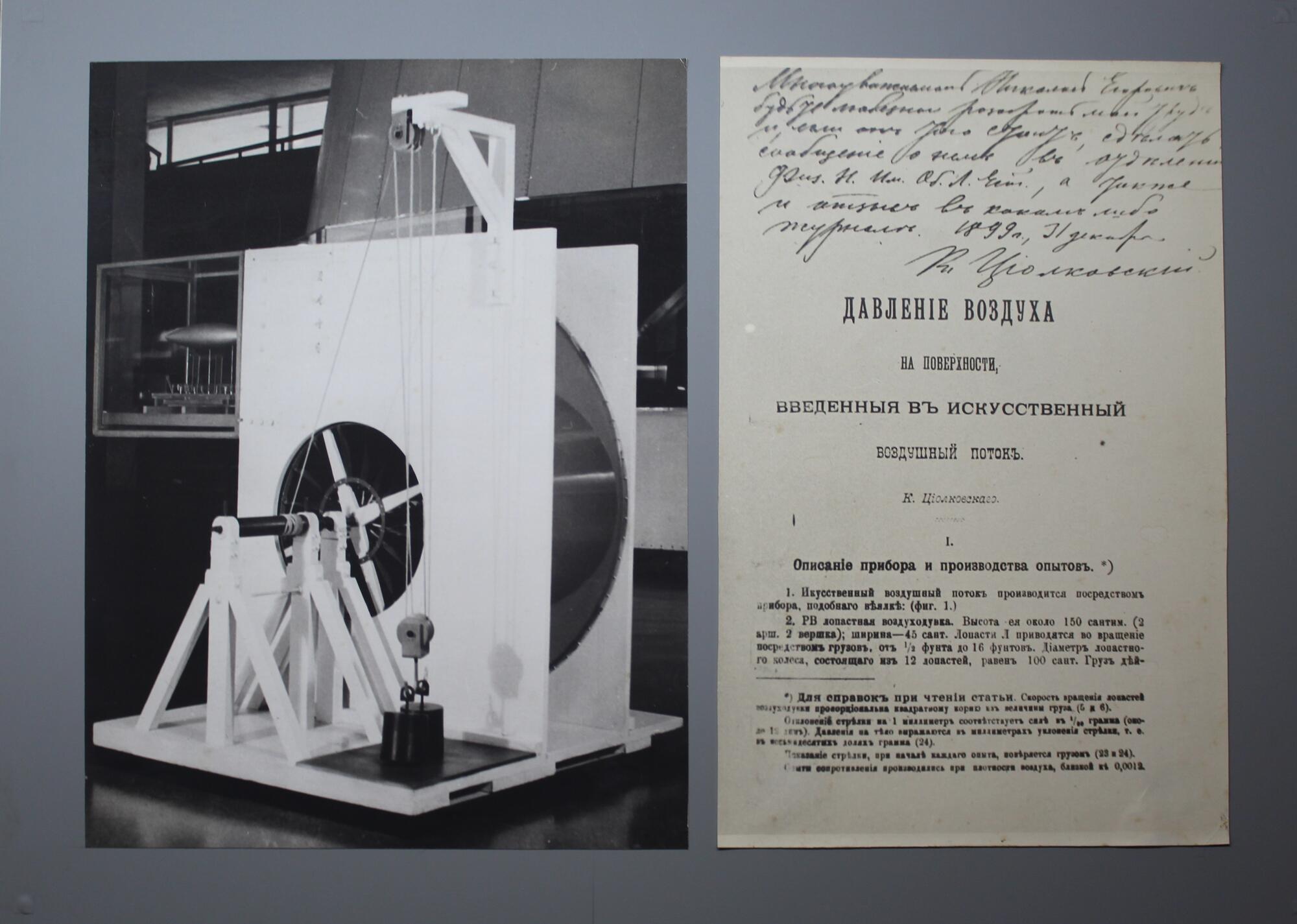

In 1897 Konstantin Tsiolkovsky built an aerodynamic pipe based on his own design. He submitted the design in a letter to the member of the Presidium of the Russian Physico-Chemical Society, Professor Alexander GershUn. This pipe was intended for research in the fields of aviation and aeronautics.

In the same year, Tsiolkovsky published an article ‘Autonomous horizontal motion of a controllable balloon’ in the journal ‘Newsletter of experienced physics and elementary mathematics’. In the material, he reported that he had created a ‘bucket-wheel blower’ for conducting experiments to study air resistance. The scientist wrote: ‘Recently, I have come up with a completely new method to do them with the use of artificial wind (bucket-wheel blower is a type of a big fanning mill)’.

Tsiolkovsky designed an aerodynamic pipe to test in the artificial air flow bodies of various geometric forms, as well as models of aircraft, which the scientist made himself out of dense paper and glue. His daughter, LyubOv, recalled: ‘The aerodynamic tube occupied a quarter of the room. Father had to sleep on a workbench. He twisted the handle of the machine, kept the account, which he recorded on paper. It was strictly forbidden to enter the room at that time’. And the scientist himself said: ‘I used to look the room with a hook so they wouldn’t distract me or disrupt the correctness of air currents. The letter-carrier knocks on the door, and it is not allowed to open the door until the end of the observation’.

Tsiolkovsky wrote and sketched all the results of the research on the sheets of writing paper, which he collected in a voluminous notebook. A single copy was sent by Tsiolkovsky to Professor Nikolai Zhukovsky.

Later, Tsiolkovsky built a larger aerodynamic pipe. He published the results of the experiments delivered with the help of this pipe in the article “Air Resistance and Aeronautics” and also used them in the works on aircraft design: whole-metal airship and aircraft with jet engine.

In the same year, Tsiolkovsky published an article ‘Autonomous horizontal motion of a controllable balloon’ in the journal ‘Newsletter of experienced physics and elementary mathematics’. In the material, he reported that he had created a ‘bucket-wheel blower’ for conducting experiments to study air resistance. The scientist wrote: ‘Recently, I have come up with a completely new method to do them with the use of artificial wind (bucket-wheel blower is a type of a big fanning mill)’.

Tsiolkovsky designed an aerodynamic pipe to test in the artificial air flow bodies of various geometric forms, as well as models of aircraft, which the scientist made himself out of dense paper and glue. His daughter, LyubOv, recalled: ‘The aerodynamic tube occupied a quarter of the room. Father had to sleep on a workbench. He twisted the handle of the machine, kept the account, which he recorded on paper. It was strictly forbidden to enter the room at that time’. And the scientist himself said: ‘I used to look the room with a hook so they wouldn’t distract me or disrupt the correctness of air currents. The letter-carrier knocks on the door, and it is not allowed to open the door until the end of the observation’.

Tsiolkovsky wrote and sketched all the results of the research on the sheets of writing paper, which he collected in a voluminous notebook. A single copy was sent by Tsiolkovsky to Professor Nikolai Zhukovsky.

No reply was received. Tsiolkovsky worried, tried to find the manuscript, but did not succeed. Later, it turned out that the notebook was simply lost among the papers of Zhukovsky. It was not found until after the death of the professor.

Later, Tsiolkovsky built a larger aerodynamic pipe. He published the results of the experiments delivered with the help of this pipe in the article “Air Resistance and Aeronautics” and also used them in the works on aircraft design: whole-metal airship and aircraft with jet engine.