The ideas of Sufism got widely spread in the Muslim world as far back as in the 12th century. This religious movement professing asceticism and stepped in mysticism was popular in the Volga-Ural region. The affiliation with Sufi brotherhood was confirmed by Silsilah, a document testifying to the transfer of theosophical knowledge from teacher to student.

Such documents were necessitated by the persecution of Islam, which, after the weakening of Kazan Khanate and its submission to Moscow, ceased to be an official religion. It was practiced secretly through the establishment of Sufi brotherhoods. In the Volga region, there was a whole Naqshbandi movement that advocated the tariqah (path) to knowledge and improvement through a close spiritual contact between the teacher and the student.

This teaching implied that its followers had to go through ten spiritual stations called maqaams. Each of them was a kind of feat, the overcoming of certain vices. In Naqshbandi, the first of such steps was tawba (repentance). Once it has been completed, a student had to gradually go through abstinence from all worldly temptations and poverty, learn to be patient and meek, learn to trust higher forces and thank Allah for everything he receives in this life. There was also the eleventh maqaam, which meant an overcome in parallel with the other ones and represented the transfer of knowledge from a teacher to a student through joint spiritual practices. They were often of occult nature including elements of alchemy.

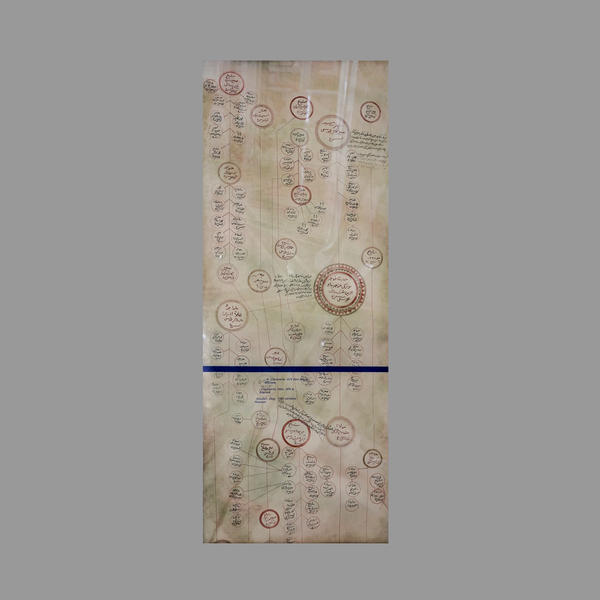

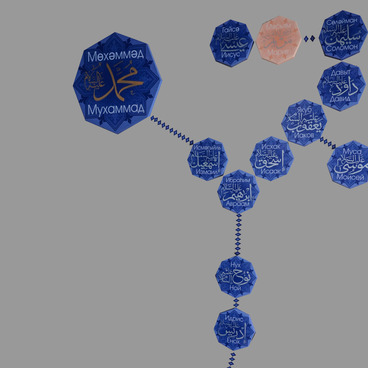

A Silsilah that translates from Arabic as a ‘chain’ was a kind of genealogical document clearly showing the connection between a teacher and his followers. Listed first in the chain were usually prophets Muhammad or Khidr, who transferred their knowledge and spiritual practices to their closest companions. For example, prophet Muhammad’s student was his cousin, the fourth righteous caliph Ali ibn Abu Talib. The knowledge was further transferred to the sheikh, who was included in the silsilah and was the only person to decide how to handle it further. It is noteworthy that the sheikh became a teacher, who chose his students and included them in the Silsilah. If his student (murid) eventually became a sheikh, he could also transfer the knowledge down the chain. A murid, who became a sheikh, could have several teachers (ishans) at the same time. But if he did not reach the sheikh’s level, the silsilah ended with him.

Such a documented spiritual chain could have a great number of branches and at times consisted of dozens of names. The practice of making silsilahs has been preserved in many Arab countries to this day.

Such documents were necessitated by the persecution of Islam, which, after the weakening of Kazan Khanate and its submission to Moscow, ceased to be an official religion. It was practiced secretly through the establishment of Sufi brotherhoods. In the Volga region, there was a whole Naqshbandi movement that advocated the tariqah (path) to knowledge and improvement through a close spiritual contact between the teacher and the student.

This teaching implied that its followers had to go through ten spiritual stations called maqaams. Each of them was a kind of feat, the overcoming of certain vices. In Naqshbandi, the first of such steps was tawba (repentance). Once it has been completed, a student had to gradually go through abstinence from all worldly temptations and poverty, learn to be patient and meek, learn to trust higher forces and thank Allah for everything he receives in this life. There was also the eleventh maqaam, which meant an overcome in parallel with the other ones and represented the transfer of knowledge from a teacher to a student through joint spiritual practices. They were often of occult nature including elements of alchemy.

A Silsilah that translates from Arabic as a ‘chain’ was a kind of genealogical document clearly showing the connection between a teacher and his followers. Listed first in the chain were usually prophets Muhammad or Khidr, who transferred their knowledge and spiritual practices to their closest companions. For example, prophet Muhammad’s student was his cousin, the fourth righteous caliph Ali ibn Abu Talib. The knowledge was further transferred to the sheikh, who was included in the silsilah and was the only person to decide how to handle it further. It is noteworthy that the sheikh became a teacher, who chose his students and included them in the Silsilah. If his student (murid) eventually became a sheikh, he could also transfer the knowledge down the chain. A murid, who became a sheikh, could have several teachers (ishans) at the same time. But if he did not reach the sheikh’s level, the silsilah ended with him.

Such a documented spiritual chain could have a great number of branches and at times consisted of dozens of names. The practice of making silsilahs has been preserved in many Arab countries to this day.