Australopithecines are a group of several ancient genera of great apes that can be described as an intermediate stage between apes and humans. The extinct species (Australopithecus africanus) lived in South Africa (modern RSA) about 3,6—2,4 million years ago.

Some species of Australopithecines were the direct ancestors of modern people. They were already walking upright, but they were not able to make real tools yet. The proportions of the bodies of these primates are far from human: they had relatively short legs and long arms, but the structure of the pelvis was similar to that of modern humans. Australopithecines were about one and a half meters in height and weighed between 20 and 45 kilograms. Another feature that made Australopithecines similar to humans was small canines of a size practically not more than the size of the other teeth.

The scientists define three groups of these great apes. Early Australopithecines existed in the period of 7—4 million years ago. They had just mastered upright walking and retained the ability to climb trees. Their descendants, also known as the Gracile Australopithecines, were upright walking and lived 4—2,5 million years ago. The Australopithecus africanus also belonged to this group. The Massive Australopithecines, or Paranthropus, as well as the very first people derived from the Gracile Australopithecines.

The first Australopithecus to be discovered by scientists was an African. The Australian anthropologist Raymond Dart described him in 1924 thanks to a fossilized skull found in the Taung quarry in South Africa.

The Australopithecus africanus was upright walking but spent a lot of time in trees. As all Gracile Australopithecines, these primates were omnivores. However, plant food prevailed in their diet.

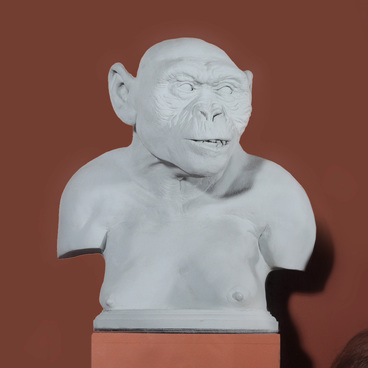

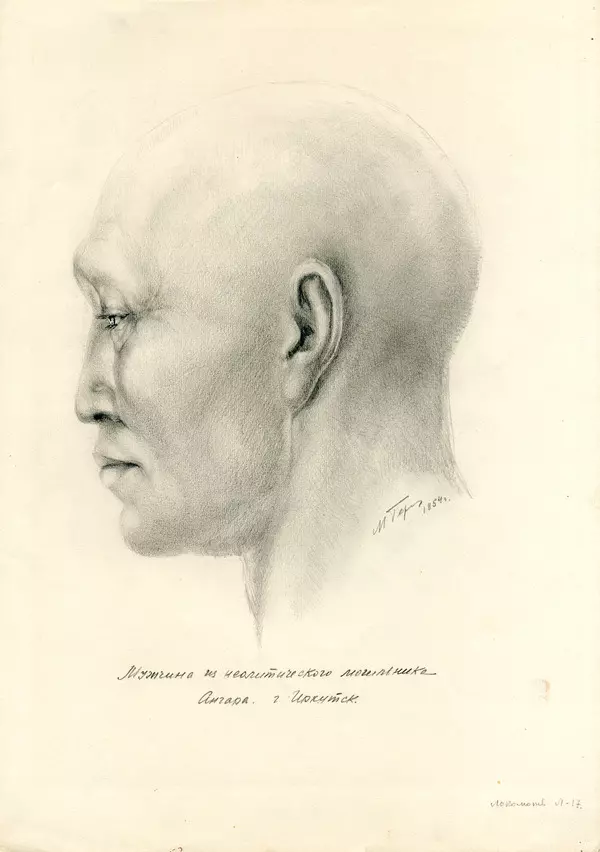

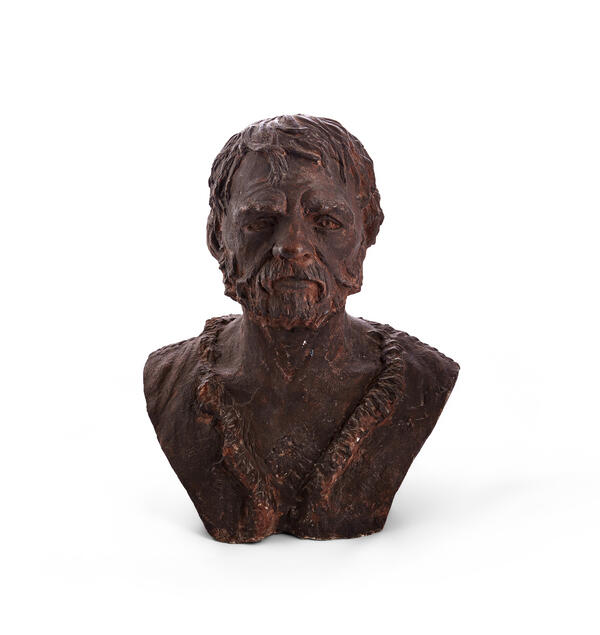

The Soviet anthropologist Mikhail Gerasimov who used his method of facial reconstruction based on skull features made the sculpture of the Australopithecus africanus presented in the exhibition. To make the reconstruction, the scientist divided the facial part of the skull into several zones with the highest peaks. He measured them using ultrasound or probed with his fingers. Then he attached pegs with an indication of the height to the copy of the skull. The more pegs there were, the more detailed the description of the relief of the face became. To restore the appearance from the skull, more than a hundred such pegs are needed.

Some species of Australopithecines were the direct ancestors of modern people. They were already walking upright, but they were not able to make real tools yet. The proportions of the bodies of these primates are far from human: they had relatively short legs and long arms, but the structure of the pelvis was similar to that of modern humans. Australopithecines were about one and a half meters in height and weighed between 20 and 45 kilograms. Another feature that made Australopithecines similar to humans was small canines of a size practically not more than the size of the other teeth.

The scientists define three groups of these great apes. Early Australopithecines existed in the period of 7—4 million years ago. They had just mastered upright walking and retained the ability to climb trees. Their descendants, also known as the Gracile Australopithecines, were upright walking and lived 4—2,5 million years ago. The Australopithecus africanus also belonged to this group. The Massive Australopithecines, or Paranthropus, as well as the very first people derived from the Gracile Australopithecines.

The first Australopithecus to be discovered by scientists was an African. The Australian anthropologist Raymond Dart described him in 1924 thanks to a fossilized skull found in the Taung quarry in South Africa.

The Australopithecus africanus was upright walking but spent a lot of time in trees. As all Gracile Australopithecines, these primates were omnivores. However, plant food prevailed in their diet.

The Soviet anthropologist Mikhail Gerasimov who used his method of facial reconstruction based on skull features made the sculpture of the Australopithecus africanus presented in the exhibition. To make the reconstruction, the scientist divided the facial part of the skull into several zones with the highest peaks. He measured them using ultrasound or probed with his fingers. Then he attached pegs with an indication of the height to the copy of the skull. The more pegs there were, the more detailed the description of the relief of the face became. To restore the appearance from the skull, more than a hundred such pegs are needed.