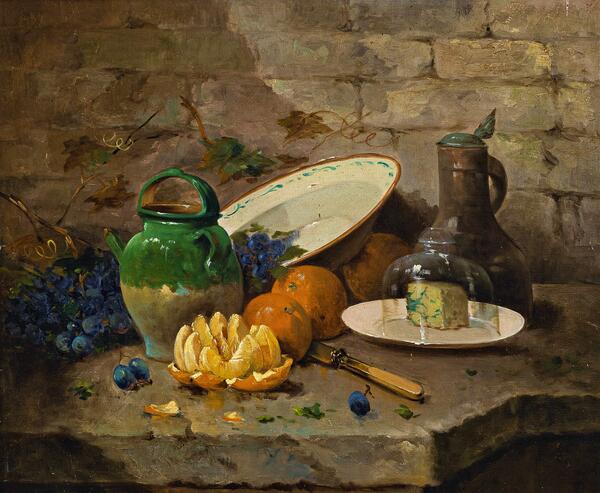

The Volsk museum gallery houses a still life painted by an artist Charles Malernet in the second half of the 19th century.

The painter depicted a composition of two ceramic vessels with wine and water next to a cut and opened lily-shaped orange. Next to them lies a freshly cut branch of grapes and cheese with noble blue mold.

The arrangement of objects in a painting corresponds to one of the popular still life types — the depiction of a set table. In past centuries, such paintings most often depicted food that was served for breakfast. Thus, Malernet’s painting shows cheese served on a saucer with a transparent glass cover.

The first work that researchers classify as a full-fledged still life was a painting by the Venetian painter Jacopo de’ Barbari in 1504. He depicted a composition with a partridge, a gauntlet, and a crossbow bolt.

Still life in Western painting emerged as a separate genre and professional specialization only at the end of the 16th century. Dutch and Flemish painters contributed a lot to this process. They also coined a term for the genre — stilleven, or ‘frozen, still life’. Until this time the depiction of inanimate objects, organized in a group, was most often a component or auxiliary part of the works of other genres.

Along with inanimate objects in still life, there were often living things. They were deliberately turned into things by getting isolated from nature: fish were painted on a table, flowers were depicted cut in a bouquet, wildfowl — caught while hunting. Motionless lizards, insects, or animals also became part of still life.

The specifics of still life included greater attention to the structure of the composition, the details of the depicted objects, the volume, and the surface texture. The painters tried to portray objects as realistically as possible, and many things were given a special meaning. Because of that, still lifes by the 17th-century European painters often became allegories and conveyed abstract notions with the help of images and pictures.

For example, rotting fruit was an allegory of aging, apples reminded of the fall of Adam and Eve, peaches and oysters endowed the painting with erotic motifs. Viewers often used special books containing instructions on how to decipher such imagery.

The painter depicted a composition of two ceramic vessels with wine and water next to a cut and opened lily-shaped orange. Next to them lies a freshly cut branch of grapes and cheese with noble blue mold.

The arrangement of objects in a painting corresponds to one of the popular still life types — the depiction of a set table. In past centuries, such paintings most often depicted food that was served for breakfast. Thus, Malernet’s painting shows cheese served on a saucer with a transparent glass cover.

The first work that researchers classify as a full-fledged still life was a painting by the Venetian painter Jacopo de’ Barbari in 1504. He depicted a composition with a partridge, a gauntlet, and a crossbow bolt.

Still life in Western painting emerged as a separate genre and professional specialization only at the end of the 16th century. Dutch and Flemish painters contributed a lot to this process. They also coined a term for the genre — stilleven, or ‘frozen, still life’. Until this time the depiction of inanimate objects, organized in a group, was most often a component or auxiliary part of the works of other genres.

Along with inanimate objects in still life, there were often living things. They were deliberately turned into things by getting isolated from nature: fish were painted on a table, flowers were depicted cut in a bouquet, wildfowl — caught while hunting. Motionless lizards, insects, or animals also became part of still life.

The specifics of still life included greater attention to the structure of the composition, the details of the depicted objects, the volume, and the surface texture. The painters tried to portray objects as realistically as possible, and many things were given a special meaning. Because of that, still lifes by the 17th-century European painters often became allegories and conveyed abstract notions with the help of images and pictures.

For example, rotting fruit was an allegory of aging, apples reminded of the fall of Adam and Eve, peaches and oysters endowed the painting with erotic motifs. Viewers often used special books containing instructions on how to decipher such imagery.