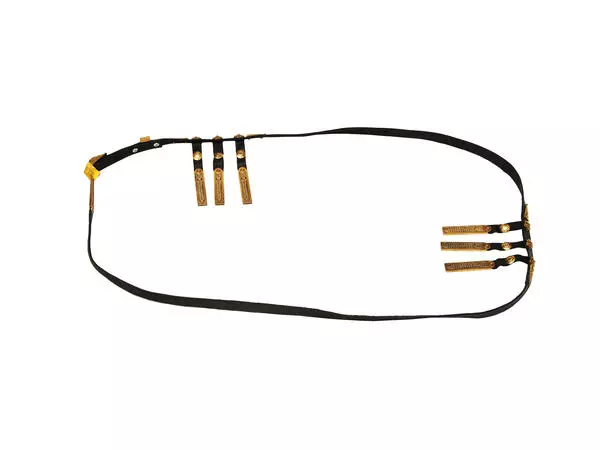

A warrior in a cherkeska, a traditional male coat of peoples of the Northern Caucasus, always carries gazyrs in his breast pockets. Gazyrs are cartridge cases made of hollow wooden, bone, or reed tubes. Initially, they were used for storing gunpowder and bullets.

It is important that a precisely measured amount of gunpowder was poured into each gazyr, because a little mistake could cost someone’s life. If there was too much explosive substance in the barrel, the weapon could explode, and if too little, it would not shoot.

The old gazyr had a decorative cap on the top, and a hole on the bottom through which a rod for firmly packing the charge — the ramrod — could pass freely. With the ramrod, they pushed a felt gasket, the wadding, into the gazyr. Then the powder was poured into the cartridge. It was plugged with a bullet wrapped in a piece of cloth. A full gazyr was held with a cloth with a bullet turned upwards.

In a battle, the bullet was pulled out of the gazyr with one’s teeth, and the powder was poured out of it and into the gun barrel. Then the wadding was hammered into the weapon with a ramrod and a bullet was placed on top along with a cloth, so it lay more tightly in the barrel. The used gazyr was put back in the pocket with its decorative cap turned upside down. This made it possible to quickly understand which case was empty.

Gazyrs appeared in the North Caucasus in the 16–17th centuries along with firearms. They were not an invention of local warriors; similar cartridge cases were used by musketeers in France and Russian streltsy (units of firearm infantry). In the Russian military tradition, a cross-belt with cartridge cases was called a ‘berendeika’.

At first, Caucasian soldiers carried gazyrs in leather cartridge belt bags, they were worn on their shoulders or attached to their belts. But this was inconvenient, so soon the covers for gazyrs began to be sewn into traditional men’s clothes — a cherkeska or a chokha. They were placed symmetrically on both sides of the chest. Thus, they did not interfere with the hand movements when riding on horseback and fighting with cold weapons. At the same time, these cases additionally protected the warrior. They were attached at a specific angle, so that, if necessary, they deflected the blows from the body.

Gradually, firearms were improved, and gazyrs lost their purpose. Over time, the cartridge pocket on the chokha has become a symbol of courage, a man’s readiness to protect his home. Therefore, gazyrs today are an integral part of traditional men’s outfits in the Northern Caucasus.

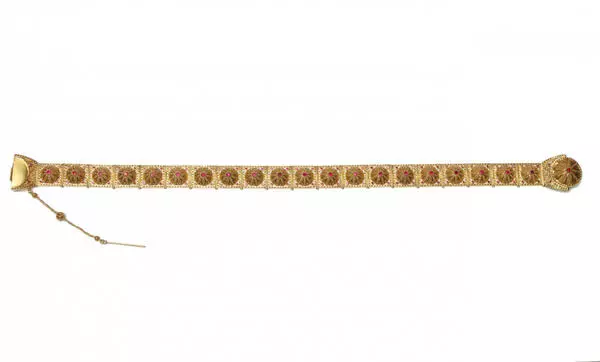

The gazyrs from the museum collection were made by jeweler Bekhan Dakhkilgov. He holds the fifth-class title (the highest) in artistic metalworking. He is the only one of the Ingush masters who can work in filigree.

It is important that a precisely measured amount of gunpowder was poured into each gazyr, because a little mistake could cost someone’s life. If there was too much explosive substance in the barrel, the weapon could explode, and if too little, it would not shoot.

The old gazyr had a decorative cap on the top, and a hole on the bottom through which a rod for firmly packing the charge — the ramrod — could pass freely. With the ramrod, they pushed a felt gasket, the wadding, into the gazyr. Then the powder was poured into the cartridge. It was plugged with a bullet wrapped in a piece of cloth. A full gazyr was held with a cloth with a bullet turned upwards.

In a battle, the bullet was pulled out of the gazyr with one’s teeth, and the powder was poured out of it and into the gun barrel. Then the wadding was hammered into the weapon with a ramrod and a bullet was placed on top along with a cloth, so it lay more tightly in the barrel. The used gazyr was put back in the pocket with its decorative cap turned upside down. This made it possible to quickly understand which case was empty.

Gazyrs appeared in the North Caucasus in the 16–17th centuries along with firearms. They were not an invention of local warriors; similar cartridge cases were used by musketeers in France and Russian streltsy (units of firearm infantry). In the Russian military tradition, a cross-belt with cartridge cases was called a ‘berendeika’.

At first, Caucasian soldiers carried gazyrs in leather cartridge belt bags, they were worn on their shoulders or attached to their belts. But this was inconvenient, so soon the covers for gazyrs began to be sewn into traditional men’s clothes — a cherkeska or a chokha. They were placed symmetrically on both sides of the chest. Thus, they did not interfere with the hand movements when riding on horseback and fighting with cold weapons. At the same time, these cases additionally protected the warrior. They were attached at a specific angle, so that, if necessary, they deflected the blows from the body.

Gradually, firearms were improved, and gazyrs lost their purpose. Over time, the cartridge pocket on the chokha has become a symbol of courage, a man’s readiness to protect his home. Therefore, gazyrs today are an integral part of traditional men’s outfits in the Northern Caucasus.

The gazyrs from the museum collection were made by jeweler Bekhan Dakhkilgov. He holds the fifth-class title (the highest) in artistic metalworking. He is the only one of the Ingush masters who can work in filigree.