Pyotr Tchaikovsky never worked at his oak desk and only used it to write answers to numerous letters. The desk features a desk pad, an inkstand, pens, pen wipers, a paperweight decorated with Florentine mosaic, keys for tuning the grand piano, a tuning fork, and the composer’s pince-nez. The faience lamp was a gift Tchaikovsky received from his student Alexander Siloti. There is a waste-paper basket under the desk.

Throughout his life, Tchaikovsky maintained a correspondence with his publisher Pyotr Jurgenson. He also famously exchanged letters with his close friend and benefactress Nadezhda von Meck who supported Tchaikovsky mentally and financially. A photograph of Nadezhda and her daughter is standing on the table.

Tchaikovsky also wrote a lot of letters to all of his relatives, friends, fellow musicians, actors, artists, playwrights, writers, and fans. In 1866, in letters to his younger brothers, the composer complained that he had to write up to five letters a day. Over the years, the number of letters was growing, and Tchaikovsky was writing up to thirty letters a day.

The archives also include Tchaikovsky’s letters from when he was a child. After leaving Votkinsk, the eight-year-old Tchaikovsky corresponded with his governess Fanny Dürbach, and at the age of ten, when he was left alone in St. Petersburg in preparations for the Imperial School of JurisprUdence, he was writing to his parents, brothers and sisters who stayed in Alapayevsk, for two years.

Tchaikovsky thought it was important to respond to everyone, and said that “the debt of politeness is equal to the debt of honor”. All incoming correspondence was stored in lower drawers of the desk; at the end of the year, servant Alexey Safronov put the letters in folders, marked the year, and added them to the family archives, which were kept safely.

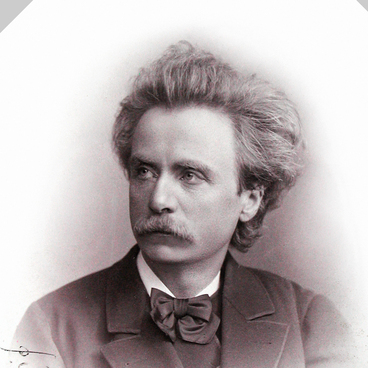

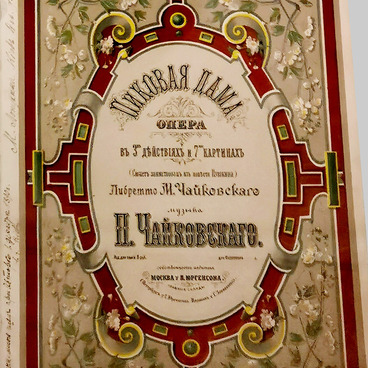

The museum contains over four thousand original letters of the composer, as well as copies of letters that are stored in other archives or with private individuals. A total of about 5 thousand letters of the composer have survived to this day, and a significant part of those has been published. Letters to European composers — Edvard Grieg, Franz Liszt, and others — were written in foreign languages.

Throughout his life, Tchaikovsky maintained a correspondence with his publisher Pyotr Jurgenson. He also famously exchanged letters with his close friend and benefactress Nadezhda von Meck who supported Tchaikovsky mentally and financially. A photograph of Nadezhda and her daughter is standing on the table.

Tchaikovsky also wrote a lot of letters to all of his relatives, friends, fellow musicians, actors, artists, playwrights, writers, and fans. In 1866, in letters to his younger brothers, the composer complained that he had to write up to five letters a day. Over the years, the number of letters was growing, and Tchaikovsky was writing up to thirty letters a day.

The archives also include Tchaikovsky’s letters from when he was a child. After leaving Votkinsk, the eight-year-old Tchaikovsky corresponded with his governess Fanny Dürbach, and at the age of ten, when he was left alone in St. Petersburg in preparations for the Imperial School of JurisprUdence, he was writing to his parents, brothers and sisters who stayed in Alapayevsk, for two years.

Tchaikovsky thought it was important to respond to everyone, and said that “the debt of politeness is equal to the debt of honor”. All incoming correspondence was stored in lower drawers of the desk; at the end of the year, servant Alexey Safronov put the letters in folders, marked the year, and added them to the family archives, which were kept safely.

The museum contains over four thousand original letters of the composer, as well as copies of letters that are stored in other archives or with private individuals. A total of about 5 thousand letters of the composer have survived to this day, and a significant part of those has been published. Letters to European composers — Edvard Grieg, Franz Liszt, and others — were written in foreign languages.