Ivan Dmitrievich Sytin built his company in a country where the population was mostly illiterate. Being a talented entrepreneur, he carefully studied the market. Lubok prints were always popular. For most people who were somewhat literate, a lubok was a familiar and most accessible printed publication. In almost every Russian house, one could see elegant pictures on the wall with a simple plot and uncomplicated text. Luboks were affordable even for the poorest buyers. They mostly depicted episodes from fairy tales, epics, historical tales and folk songs.

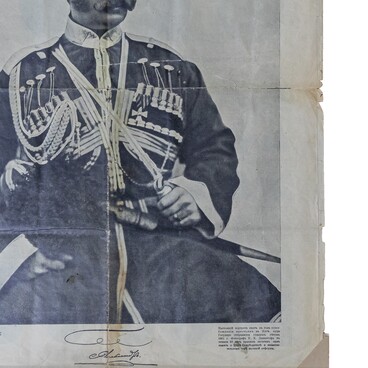

In an effort to raise the artistic level of the prints, and of course the number of sales, Ivan Sytin collaborated with the famous artist and sculptor Mikhail Osipovich Mikeshin, who created the monument “The Millennium of Russia” in Veliky Novgorod, as well as the sculptures of Catherine II in St. Petersburg, Alexander III in Rostov-on-Don, and Bogdan Khmelnitsky in Kyiv. Sytin’s collaboration with Mikeshin was fruitful, although short-lived: the tandem soon broke up. However, in 1896, they released the lubok print “A Gypsy, a Peasant and His Mare”.

This lubok consists of six colored pictures with captions framed by a striking floral pattern and narrates the adventure of the peasant Epiphan and his meeting with a gypsy. The writer and playwright Alexander Nikolayevich Ostrovsky rendered this tale in a poetic form in the folk style. However, despite the high artistic level of the drawings and incredible poetic captions, the print never gained popularity.

What was the matter? There was little demand for satire in lubok art. Villagers saved every penny and did not want to spend money on such images or, as they called them, jibes and bagatelles. It was considered shameful to buy such prints, as in addition to its informative function, a lubok image was to decorate a wall in the house. A picture of such satirical content, that even ridiculed peasant ignorance, could not be hung in the house next to sacred icons.

So, despite all efforts, Sytin’s firm could not

make the artistic lubok popular among villagers. However, lubok prints that

were in demand and sold in huge numbers also increased book sales. There was a

correlation between these two types of publications.