The publication of the complete works is always an indicator of high appreciation of the author’s work, recognition of one’s significant contribution to literature. The Complete Works of Ivan Bunin were published in 1915. By this time, the writer had already won the Pushkin Prize twice and received the title of Honorary Academician of the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences in the category of fine literature.

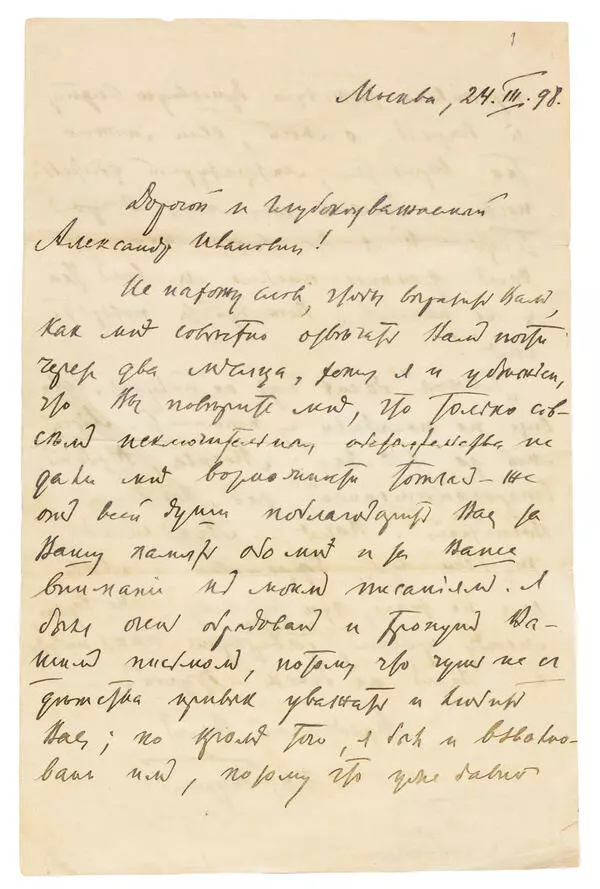

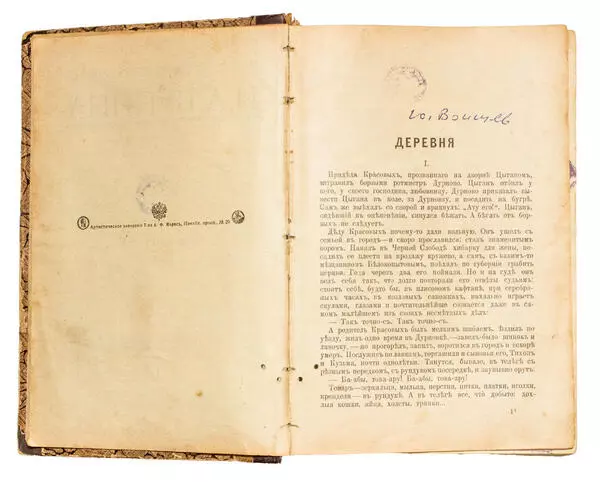

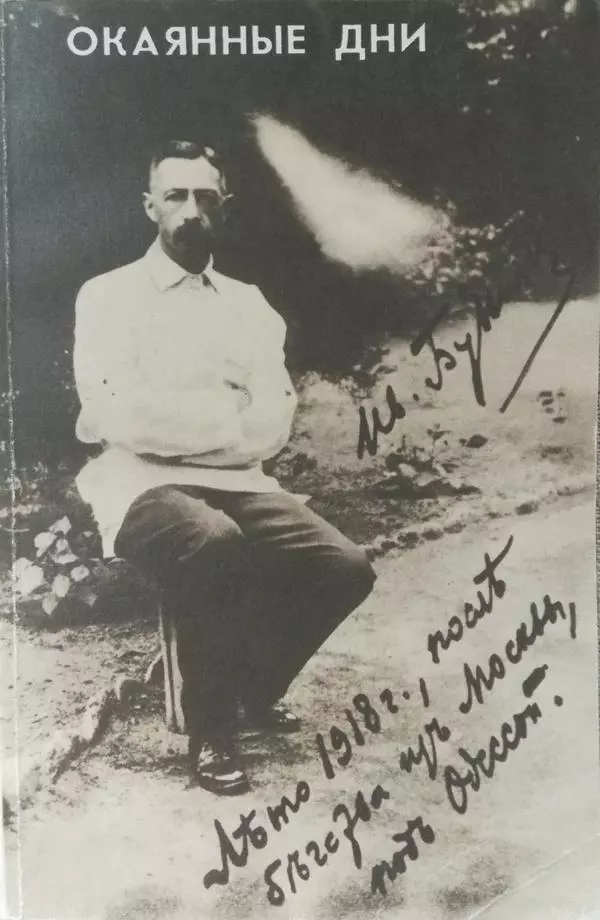

Bunin signed a contract with the St. Petersburg publishing house ‘A. F. Marx Partnership’ in early May 1913: the parties agreed on the release of six volumes, which were published as a free appendix to the magazine ‘Niva’. The author worked on the preparation of texts for printing from May to the beginning of June 1914, at that time he lived at a dacha (country house) near Odessa.

The collected works were published with an impressive print run of 200,000 copies. They covered different periods of the writer’s work and included poetry, prose and translations. According to Bunin himself, it included “everything that <…> is more or less worthy of printing”.

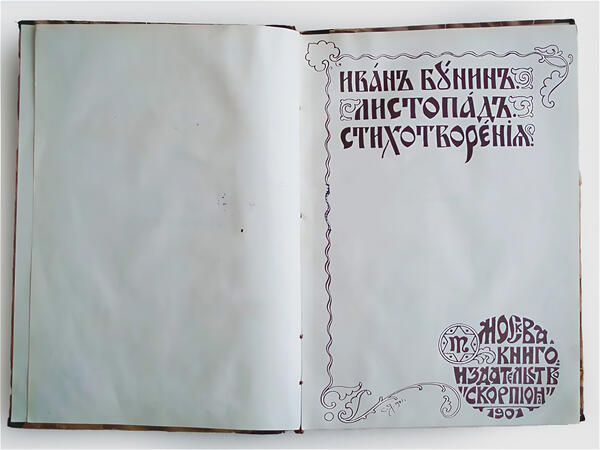

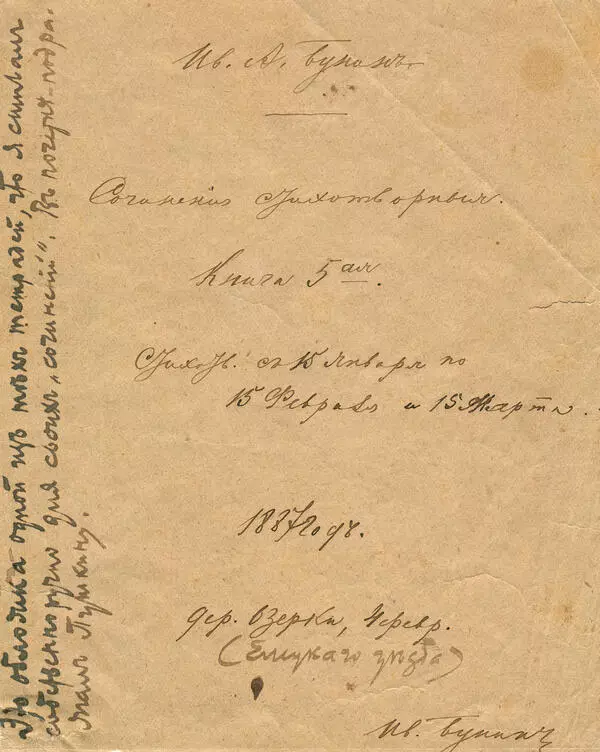

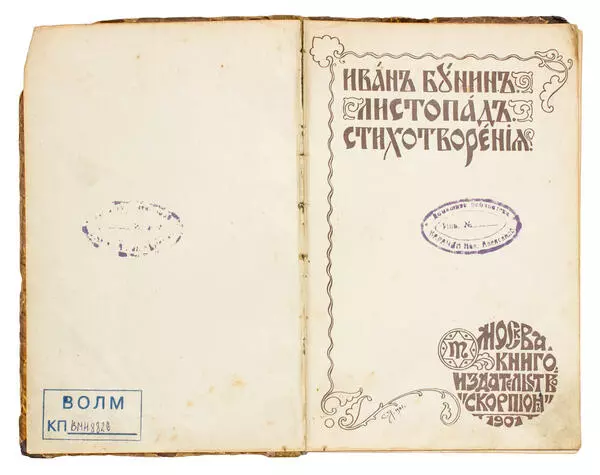

The author chose his poetic works for the first volume: early poems, as well as the cycle “Falling Leaves” and his translation of the poem “The Song of Hiawatha” by American Romantic Henry Longfellow. This choice was natural, because Bunin’s first published work was a poem. It was called ‘Over Nadson’s Grave’ and published in the magazine “Rodina” in 1887. The first book of the master was also a poetry collection, it was published in 1891 in the city of Orel by the printing house of the newspaper “Orlovsky Vestnik”.

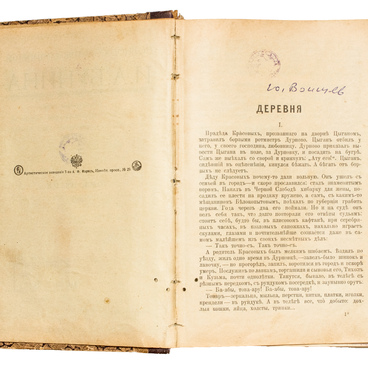

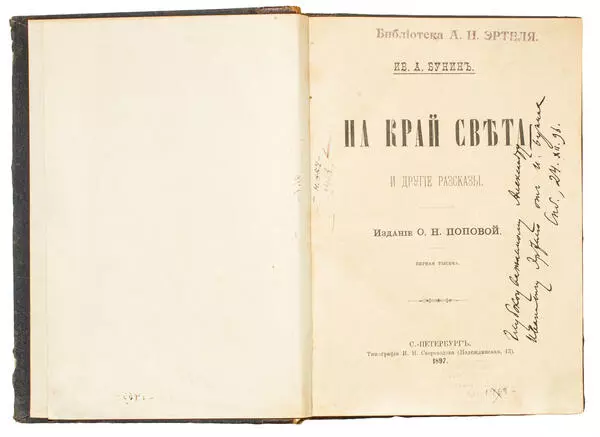

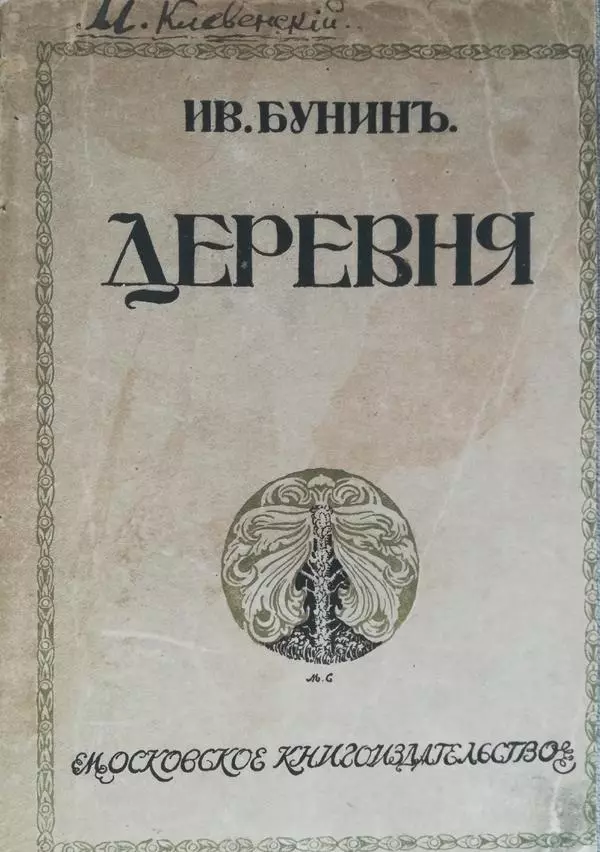

The second volume of the collection includes stories written in 1892-1902, such as: “A Village Sketch”, “Kastryuk”, “At the Khutor”, “At the Dacha”, “The Fantasy Man”, “News from Motherland”, “To the Edge of the World”, “Antonov Apples” and others.

“Antonov Apples” is one of the most famous stories of Bunin. He published it in 1900. At first, the text caused a stir among his contemporaries: the author was accused of not having a central idea. Potapenko’s review stated that Bunin writes ‘beautifully, intelligently, colorfully, you read him with pleasure and still can’t get to the main thing’, because he “describes everything that comes to hand”.

A brilliant answer to this assessment was given by writer Valentin Kataev:

Bunin signed a contract with the St. Petersburg publishing house ‘A. F. Marx Partnership’ in early May 1913: the parties agreed on the release of six volumes, which were published as a free appendix to the magazine ‘Niva’. The author worked on the preparation of texts for printing from May to the beginning of June 1914, at that time he lived at a dacha (country house) near Odessa.

The collected works were published with an impressive print run of 200,000 copies. They covered different periods of the writer’s work and included poetry, prose and translations. According to Bunin himself, it included “everything that <…> is more or less worthy of printing”.

The author chose his poetic works for the first volume: early poems, as well as the cycle “Falling Leaves” and his translation of the poem “The Song of Hiawatha” by American Romantic Henry Longfellow. This choice was natural, because Bunin’s first published work was a poem. It was called ‘Over Nadson’s Grave’ and published in the magazine “Rodina” in 1887. The first book of the master was also a poetry collection, it was published in 1891 in the city of Orel by the printing house of the newspaper “Orlovsky Vestnik”.

The second volume of the collection includes stories written in 1892-1902, such as: “A Village Sketch”, “Kastryuk”, “At the Khutor”, “At the Dacha”, “The Fantasy Man”, “News from Motherland”, “To the Edge of the World”, “Antonov Apples” and others.

“Antonov Apples” is one of the most famous stories of Bunin. He published it in 1900. At first, the text caused a stir among his contemporaries: the author was accused of not having a central idea. Potapenko’s review stated that Bunin writes ‘beautifully, intelligently, colorfully, you read him with pleasure and still can’t get to the main thing’, because he “describes everything that comes to hand”.

A brilliant answer to this assessment was given by writer Valentin Kataev: