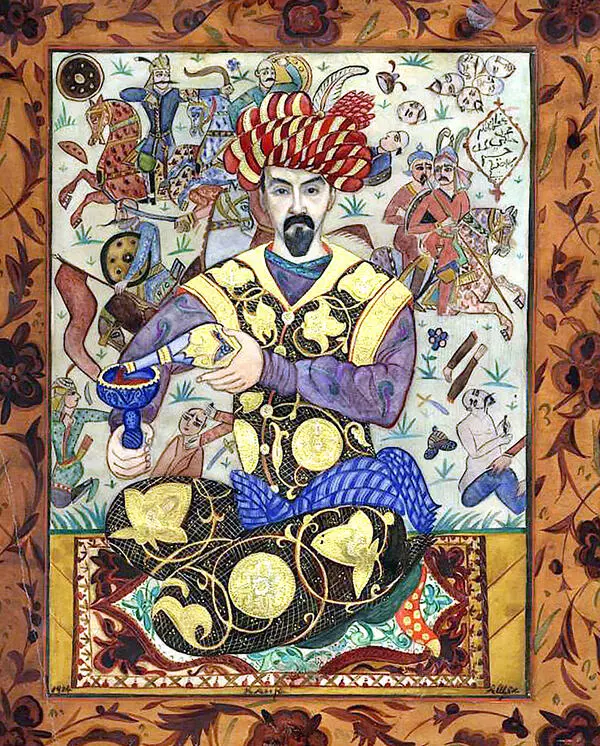

The Russian artist Alexandra Vasilievna Shchekatikhina-Pototskaya painted the presented study in 1927 in La Favière, where she spent the summer months in a Russian colony with her family — her husband, the Russian painter Ivan Bilibin, and her son Mstislav.

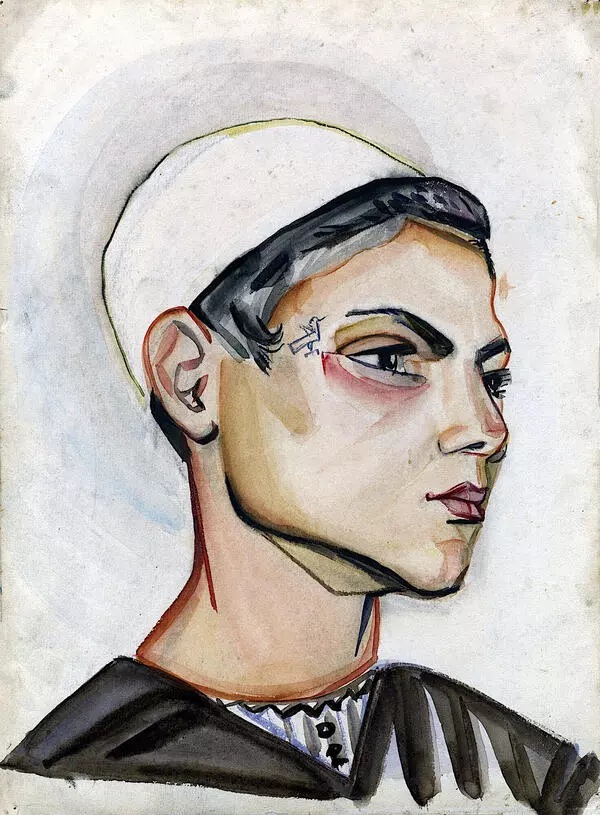

The artist depicted a group of elderly people who are accustomed to hard work, but who, in a moment of rest, decorously sit in a row on the embankment in festive costumes. Shchekatikhina-Pototskaya managed to convey the clumsiness, shyness and confusion of the old fishermen.

The days spent by the sea in La Favière were for the inhabitants of the colony a heavenly time in exile. Domestic disarray and living on an almost abandoned seashore in a pine forest did not bother the hermit settlers. Swimming in the warm sea, the beach, sailing, fishing, conversations with friends at the tea table — this serene rest brought them spiritual fulfilment.

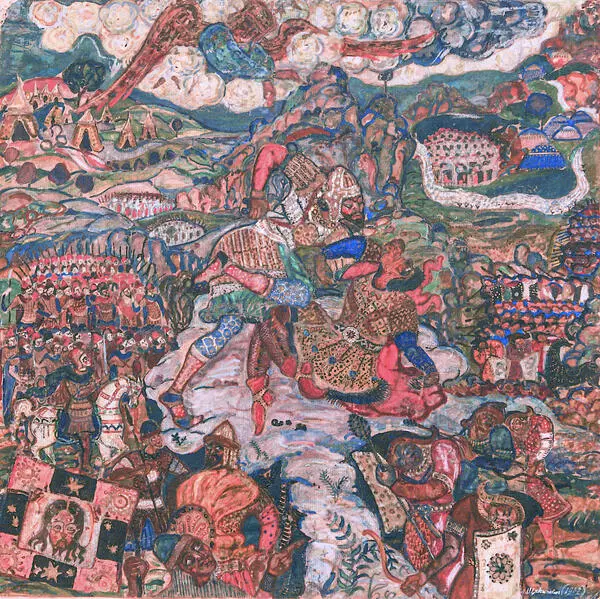

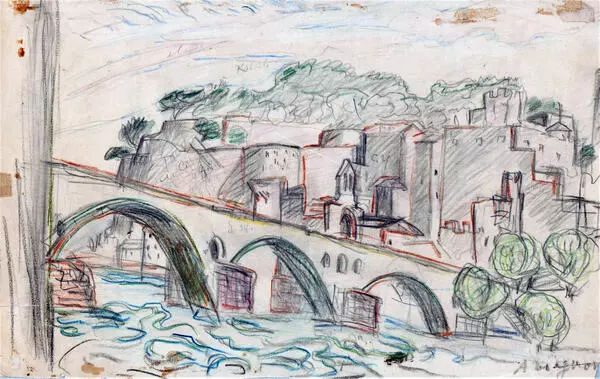

Bilibin and Shchekatikhina walked all the trails there, saw all the corners, visited all the local attractions. And, as always, they drew a lot. Shchekatikhina was fascinated with panoramas: the expanse of the sea, coastal hills overgrown with forest and greenery, bays, and modest cottages on the shore. She worked both on fine days and in bad weather, when the Mediterranean mistral (cold dry wind) enveloped the village, the squally stormy winds rolled ashore, and trees bent to the ground. Alexandra Vasilievna painted a lot with oil, often the same landscapes from different angles. These works differed from her decorative porcelain paintings and picturesque still lifes. In landscapes, she is also original and peculiar. One cannot confuse her brush stroke with anyone else’s. The painting is expressive, the brush is subordinated to the artist’s temperament. The colors are pure, transparent and light.

Most of the artist’ works were for sale. They were inexpensive and were acquired mainly by collectors and representatives of the Russian diaspora. Educated in the traditions of the Russian national school, Bilibin and Shchekatikhina did not strive for, and could not join the fashionable Parisian artistic circles. They had very little money. The crisis that began in the 1930s completely impoverished them. Like many other “unfashionable” artists, they were destitute and began to seriously consider returning to their native lands.

The artist depicted a group of elderly people who are accustomed to hard work, but who, in a moment of rest, decorously sit in a row on the embankment in festive costumes. Shchekatikhina-Pototskaya managed to convey the clumsiness, shyness and confusion of the old fishermen.

The days spent by the sea in La Favière were for the inhabitants of the colony a heavenly time in exile. Domestic disarray and living on an almost abandoned seashore in a pine forest did not bother the hermit settlers. Swimming in the warm sea, the beach, sailing, fishing, conversations with friends at the tea table — this serene rest brought them spiritual fulfilment.

Bilibin and Shchekatikhina walked all the trails there, saw all the corners, visited all the local attractions. And, as always, they drew a lot. Shchekatikhina was fascinated with panoramas: the expanse of the sea, coastal hills overgrown with forest and greenery, bays, and modest cottages on the shore. She worked both on fine days and in bad weather, when the Mediterranean mistral (cold dry wind) enveloped the village, the squally stormy winds rolled ashore, and trees bent to the ground. Alexandra Vasilievna painted a lot with oil, often the same landscapes from different angles. These works differed from her decorative porcelain paintings and picturesque still lifes. In landscapes, she is also original and peculiar. One cannot confuse her brush stroke with anyone else’s. The painting is expressive, the brush is subordinated to the artist’s temperament. The colors are pure, transparent and light.

Most of the artist’ works were for sale. They were inexpensive and were acquired mainly by collectors and representatives of the Russian diaspora. Educated in the traditions of the Russian national school, Bilibin and Shchekatikhina did not strive for, and could not join the fashionable Parisian artistic circles. They had very little money. The crisis that began in the 1930s completely impoverished them. Like many other “unfashionable” artists, they were destitute and began to seriously consider returning to their native lands.