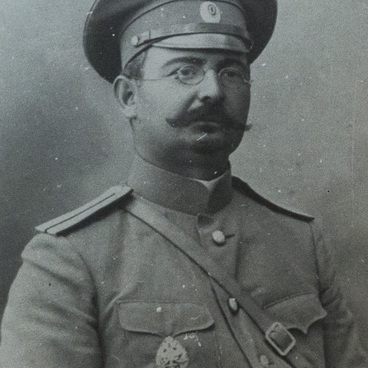

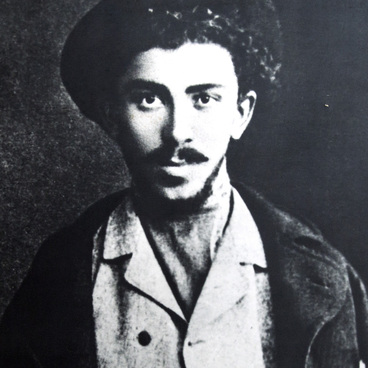

Kosta Khetagurov wasn’t only a famous poet and publicist, but also a talented artist. His workformed the basis for the traditions of easel and fresco painting, as well as decorative art, in Ossetia and other places where the mountain peoples of the North Caucasus live.

Khetagurov worked on the painting “Child masons” from 1886 until 1891, the end of his exile. But the canvas remained unfinished; the artist had to spend more time on the orders that served as his main source of income, and simply did not have time to finish the painting.

This work by Khetagurov garned much response. Ossetian artist Maharbek Tuganov wrote: “The back-breaking work of an Ossetian boy sitting with a heavy hammer under the sun, drops of sweat streaming down his cheeks, and wearing clothes suited to a beggar, are clear indications of the artist”s intentions. In the middle of the Caucasus”s grandiose, charming nature is the hard work of poor children.”

Publicist Mikhail Bulkaty noted: “The boy”s sad smile says a lot, but it is no less expressive than his brother”s gesture. The inconspicuous details in Kosta”s painting not only complement the overall picture, they create an atmosphere that helps reveal the characters ' nature. The unity of reality and high ideals has always been the yardstick, the benchmark of his work, both in his paintings and in his poetry. The outer view, the shell hide the essence of each particular picture quite snugly; the viewer has to open his mind in order to penetrate the content. The piece of stone held by one of the child masons is not just a detail in the painting. Compositionally, this gesture sublimates the tragedy of these of two boys”s existence… The hand holding the piece of newly broken stone is not the hand of one boy, but of all boys and, perhaps, of the entire Caucasus. Two boys in rags, a mutt next to them, and an empty knapsack hanging on a twisted telegraph pole: this is the symbol of Ossetia.”

Artist Yevgeny Adelberg considered “Child Masons” to be one of Khetagurov’s most important paintings: ‘Kosta Levanovich Khetagurov comes close to the Peredvizhniki (traveling artrists). By its democratic orientation the story it chooses to tell, Kosta echoes’ Troika’, by V. G. Perov.’

Khetagurov worked on the painting “Child masons” from 1886 until 1891, the end of his exile. But the canvas remained unfinished; the artist had to spend more time on the orders that served as his main source of income, and simply did not have time to finish the painting.

This work by Khetagurov garned much response. Ossetian artist Maharbek Tuganov wrote: “The back-breaking work of an Ossetian boy sitting with a heavy hammer under the sun, drops of sweat streaming down his cheeks, and wearing clothes suited to a beggar, are clear indications of the artist”s intentions. In the middle of the Caucasus”s grandiose, charming nature is the hard work of poor children.”

Publicist Mikhail Bulkaty noted: “The boy”s sad smile says a lot, but it is no less expressive than his brother”s gesture. The inconspicuous details in Kosta”s painting not only complement the overall picture, they create an atmosphere that helps reveal the characters ' nature. The unity of reality and high ideals has always been the yardstick, the benchmark of his work, both in his paintings and in his poetry. The outer view, the shell hide the essence of each particular picture quite snugly; the viewer has to open his mind in order to penetrate the content. The piece of stone held by one of the child masons is not just a detail in the painting. Compositionally, this gesture sublimates the tragedy of these of two boys”s existence… The hand holding the piece of newly broken stone is not the hand of one boy, but of all boys and, perhaps, of the entire Caucasus. Two boys in rags, a mutt next to them, and an empty knapsack hanging on a twisted telegraph pole: this is the symbol of Ossetia.”

Artist Yevgeny Adelberg considered “Child Masons” to be one of Khetagurov’s most important paintings: ‘Kosta Levanovich Khetagurov comes close to the Peredvizhniki (traveling artrists). By its democratic orientation the story it chooses to tell, Kosta echoes’ Troika’, by V. G. Perov.’