The state of the Golden Horde, or Ulus Dzhuchi, existed from the early 13th century to the mid-15th century. Despite its bellicose policies, the Horde left a rich cultural heritage, such as original pottery. Cities in the Lower Volga Region excelled in this sphere.

The development of trade there gave rise to a special ornamental art, which combined elements of both Muslim and non-Muslim cultures along with the creativity of nomads. Vessels were made of kashi base here. Kashi was a mixture of quartz sand, white clay, lime, and other impurities that allowed the items to be fired at high temperatures of 1000-1200 degrees Celsius. Externally, kashi resembled Chinese porcelain. The high firing temperature produced a transparent alkaline glaze on the surface, and the white base under the glaze allowed for a variety of colored patterns. The Golden Horde borrowed the technology of making fritware from the masters of Central Asia, Iran, and Syria in the 13th — 14th centuries. In the ornaments of fritware, artists combined symbols of peoples who were part of the Golden Horde (lotus, vine, and grapevine) with geometric patterns — six-pointed stars, stripes, squares, circles, and a grid. Sometimes the ornamentation was supplemented with Arabic script.

Large cities of the Golden Horde were known for their wealth and prosperity. Craftsmen wishing to become rich came here from different countries, including those where traditions of ceramic production had already been formed.

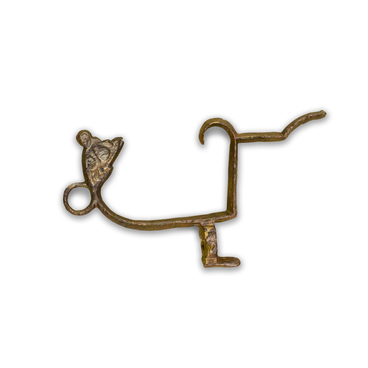

Jugs, bowls, plates, and gulabdans were made in the cities of the Volga region. Gulabdan is a type of ceremonial medieval tableware where the nobility washed their hands after a meal. The word literally means ‘rose water vessel’ in Persian: gul means ‘rose’, ab means ‘water’, dan means ‘vessel’.

These items have always had the same features: they resembled an inverted cone with a rounded bottom and ring-shaped tray. The upper edge, the ‘arms’, was molded slightly bent, where the main ornament was placed. Six cone-shaped overlays were attached to the ‘arms’. In one of such cones, there was a special groove for water drainage.

The development of trade there gave rise to a special ornamental art, which combined elements of both Muslim and non-Muslim cultures along with the creativity of nomads. Vessels were made of kashi base here. Kashi was a mixture of quartz sand, white clay, lime, and other impurities that allowed the items to be fired at high temperatures of 1000-1200 degrees Celsius. Externally, kashi resembled Chinese porcelain. The high firing temperature produced a transparent alkaline glaze on the surface, and the white base under the glaze allowed for a variety of colored patterns. The Golden Horde borrowed the technology of making fritware from the masters of Central Asia, Iran, and Syria in the 13th — 14th centuries. In the ornaments of fritware, artists combined symbols of peoples who were part of the Golden Horde (lotus, vine, and grapevine) with geometric patterns — six-pointed stars, stripes, squares, circles, and a grid. Sometimes the ornamentation was supplemented with Arabic script.

Large cities of the Golden Horde were known for their wealth and prosperity. Craftsmen wishing to become rich came here from different countries, including those where traditions of ceramic production had already been formed.

Jugs, bowls, plates, and gulabdans were made in the cities of the Volga region. Gulabdan is a type of ceremonial medieval tableware where the nobility washed their hands after a meal. The word literally means ‘rose water vessel’ in Persian: gul means ‘rose’, ab means ‘water’, dan means ‘vessel’.

These items have always had the same features: they resembled an inverted cone with a rounded bottom and ring-shaped tray. The upper edge, the ‘arms’, was molded slightly bent, where the main ornament was placed. Six cone-shaped overlays were attached to the ‘arms’. In one of such cones, there was a special groove for water drainage.